Summer is traditionally the time for disaster movies, so in the spirit of the season I’d like to bring you one of my most embarrassing disasters against Shredder, the computer chess program. In fact, I might even do a whole series of them. Believe me, I have plenty of material for such a series!

My previous posts may have given you the impression that I have fought Shredder on something close to even terms. That is definitely not the case. For every win there have probably been two losses, at least. Sometimes they are blowouts; I hang a piece in the opening or something. But the worst losses are the ones that I really could have won, and have nothing but my own stupidity to blame.

I’m writing these posts to make fun out of my stupidity, but I’ll also pick disasters that I think there is something to learn from. So let’s go. Our first game is one from last year that I managed to blow not once but twice.

Position after 35. … ed. White to move.

Position after 35. … ed. White to move.

FEN: 5rk1/1p1q1npp/r2p1P2/p1pN2P1/P1PpP3/1P1R3P/4Q2K/3R4 w – – 0 36

Position 1. I’m White here, and we have just traded knights on d4. This is what I would call an “embarrassment of riches” position. Against a human opponent I would be 99 percent sure of winning. What should I do? There are so many options! I could play Ne7+, or fg, or Qh5, or even g6. The only thing I don’t want to do is allow him to consolidate his position with … g6 and … Ne5.

Although it was a long time ago, if memory serves me correctly I spent most of my time analyzing the “nuclear option” 36. g6, which blows the position wide open. But I could not find a clear advantage for White, so I started looking at the other moves. I was a little bit pressed for time, so when I looked at 36. Qh5? and thought it was clearly winning, that was the move I played. Do you see what I overlooked? What should I have played?

(Answers below.)

Thirty moves later, thanks to some missteps by Shredder, I once again had a winning position.

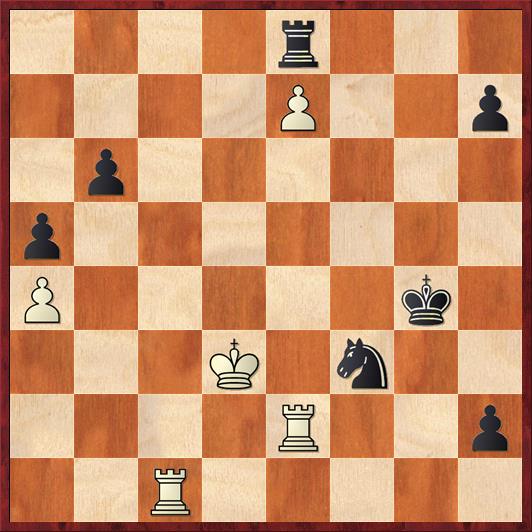

Position after 65. … Kg4. White to move.

Position after 65. … Kg4. White to move.

FEN: 4r3/4P2p/1p6/p7/P5k1/3K1n2/4R2p/2R5 w – – 0 66

Position 2. Here I played 66. Rf1? and I was only able to draw. What did I miss? What would be a better winning try? I’ll give you a little hint. The winning move is one that I could barely even bring myself to analyze seriously, because it was so repugnant.

Answers.

Position 1. The trick I missed was that after 36. Qh5? g6! (expected, of course) 37. Ne7+ Black doesn’t have to play … Kh8 but can play 37. … Qxe7! instead. White wins the exchange for a pawn but the attack disappears completely. After 38. fe gh 39. efQ+ Kxf8, we have reached an endgame position that is really excellent for Black’s knight. White has a lot of weaknesses and the knight has many good squares. Even though White is nominally ahead in material, Black has very good drawing chances.

The solution is simply to play the two key moves, Ne7+ and Qh5, in the opposite order. This is something I have written about many times — when you see two good moves, A and B, consider playing them in the reverse order — but I forgot to do it here. The point, of course, is that after 36. Ne7+! Black cannot take the knight because he would just lose a queen. So he has to play 36. … Kh8 and now I play 37. Qh5 with the threat of Ng6+. And there is nothing he can do about it, because if he moves the rook from f8 then I will win his knight. So he has to give up the exchange, and more importantly the queens stay on the board and his king remains under a heavy attack.

Nothing hard about this at all. I think that there were two reasons for my failure. First, I analyzed the most complicated move (36. g6) first. Here my bias for wild complications showed, and it’s a thought pattern I should watch out for. It makes much more sense, most of the time, to analyze the simplest move first. This is especially true in time pressure, or in blitz games, or in positions where you are clearly ahead. When you are behind, that’s the time to look for complications and try to scramble the position up.

Second, I forgot to look at both possible move orders. This is something I’ve written and lectured about many times, but I still forgot to do it. When you see two moves, A and B, that “go together,” make sure to look at them in both orders. You’ll be amazed at how often the less obvious move order is better. (In this case I think both move orders are equally “obvious,” and my problem was simply that I thought that A followed by B was good enough so I didn’t even consider B followed by A.)

Position 2. First, what I missed was that after 66. Rf1? h5 67. Re4+ Kg3 68. Re3 I win the knight but not the game. Shredder played 68. … Kg2! 69. Rexf3 h1Q and after everything gets liquidated we get to a R+P endgame that is a dead draw. In fact, it offered a draw here, which I accepted.

In this case, the reason for my failure was that I could not bring myself to take seriously the groveling defensive move 66. Rh1!, which wins. This is again all about personal biases. I hate playing defense. Not only that, in rook and pawn endgames it is almost always wrong to put your rook in front of his passed pawn.

What makes this position different? First, it’s not really a R+P endgame; it’s two rooks versus rook and knight. To some extent it’s okay to let one of my rooks become passive as long as the other one is active. They’re a team.

But more concretely than that, I had to realize that the h2 pawn is public enemy number one. It must be stopped, and there is no better way to stop it than to blockade it. Rf1 doesn’t do the job, because as soon as Black plays … Ng1 (which is coming sooner rather than later) the pawn is un-stopped again.

After 66. Rh1!, if Black plays 66. … Kg3 as in the game, White simply shrugs his shoulders and ignores it. With 67. Kc4 he threatens to march his own king up the board toward pay dirt. Now if Black plays his remaining trump card, 67. … Ng1, White wins easily with 68. R2xh2 Rxe7 69. Rxh7. Because his knight is hanging, Black has to allow a trade of rooks, and then the win for White is easy.

If Black tries to counter this plan with 66. Rh1! Kf5 67. Kc4 Ne5+ 68. Kd5, the e-pawn is taboo because of 68. … Rxe7 69. Rf1+. Notice how White has saved the move Rf1 for a time when it actually does something.

So what do we learn from Position 2? I’ll offer one possible lesson. We all have biases, but if you can’t eliminate them at least you should be aware of your biases and be prepared to compensate for them. I’m biased against playing purely defensive moves, but there are plenty of positions where there’s an obvious defensive move that just has to be played. Grit your teeth and do it. Maybe this is a second lesson: Sometimes you gotta grovel. (By the way, this is one reason that the game in my last post, where I beat Shredder with a long sequence of mostly defensive moves, was such a great psychological victory for me.)

What do you think? Do you like this idea of a “disaster movie” series? What do you think about the principle of analyzing the simplest move first? Have you been able to apply the “reversing the move order” trick in your own games? Do you know what your own biases are? Have you had any cases where you were too proud to grovel, and it cost you the game?