Time flies! We’re now up to 1975, which was the year of my graduation from prep school (Phillips Academy) and the start of my freshman year in college (Swarthmore College). Another major event during the year was my family’s move from Indianapolis, Indiana, to Richmond, Virginia.

I think of 1975 also as the first year of calm, the first year of the 1970s that fully belonged to the 1970s and was not a hangover from the 1960s. Richard Nixon was gone. The Vietnam War was over and North Vietnam won. The biggest concerns in the second half of the decade were the inflation rate (which often topped 10 percent, a far cry from the 2-3 percent most Americans are used to today) and the emergence of OPEC, which led to gas rationing in 1973 and 1979. But these things barely registered for me.

For my parents, trying to buy a house and pay two college tuitions (myself and my sister), inflation probably meant a lot. But I was sheltered, and I tend to be oblivious to my surroundings by nature.

As for the gas crisis, that had even less impact. I wasn’t even driving yet in 1973. In 1975 I got my first driver’s license; in fact, that was a big part of my summer vacation. Technically, I think it was a learner’s permit. I could drive, but only with an adult in the vehicle. After a few harrowing experiences with me behind the wheel, my parents wisely and sensibly decided I was not ready for my own car. I didn’t own a car until 1981, when I was 22 years old and really needed one for a part-time job.

Anyway, let’s talk about chess and my senior year of prep school. Reading my diary, it’s clear that my chess activity at this time was mostly connected to my prep school chess club. I played only two rated tournaments in 1975, one in March and one right after Christmas. So it seems like a drought for me chess-wise, but that was not true at all. As president of the chess club, I was the one who organized matches with other schools (three of them, all of which we won) and co-organized the Interschols, a tournament among six prep-school teams in the area (which we also won, by a narrow margin). I was very proud of the fact that we never lost a match in my three years at Andover and won Interschols every year. As top board on the chess team, I finished the year with a 6-1 record, marred only by one loss in the Interschols. None of these events were rated, but they meant more to me than the two rated events I played.

So it seems appropriate that for 1975 I should show you a game from chess club. My opponent, Sam Landsberger, was around our fifth or sixth board, and probably a class-D level player. Nevertheless, I was very proud of this game. It made such an impression on me that I wrote about it in my diary three times.

2/18: “I played an interesting Budapest Gambit against Sam Landsberger, who put up excellent defense against my attack for a while.”

2/28: “Believe it or not, I spent about four and a half hours at the chess board today, Two of them were spent on my game with Sam Landsberger. In the crucial position where Sam, pressed for time, accepted a piece sacrifice (I had also sacrificed the exchange earlier) that led to a mate-in-four, I discovered a spectacular combination that would lead to a win even against the most ingenious defense. Although I did not see either the ingenious defense or the spectacular refutation during the game, they still make everything that happened from the original exchange sacrifice on completely sound, and they make the game probably my best ever, for clarity, solidity, coherence, and also elegance. I had a feeling even as I was playing it that I was going to create a masterpiece, and I did.”

3/6: “I showed Daddy my chess masterpiece against Sam Landsberger, and managed to explain the soundness of the attack convincingly. Was he impressed? I doubt it.”

Wow. Lots to unpack here. First, there was only one other time in my life when I felt during the game that I was playing a masterpiece. That was my 2006 win over IM David Pruess, which I think legitimately was a masterpiece.

Alas, the game against Landsberger was not a masterpiece. The computer is particularly cruel to this game. Almost every move that I thought was a brilliancy was in fact a blunder. Both players were trying to outwit the other with fantastic ideas, when simple chess would have been better.

But playing over this game makes me think that perhaps we should judge the games of chess learners in a different way from masters. We should give up on the goal of 100 percent soundness and recognize that mistakes are going to happen. Instead of asking for zero mistakes, we should ask: How much originality is there? How much fighting spirit? These qualities can’t be taught, while accuracy can be, either by a coach or by lots of experience. And if, as in this game, I play an unsound move against a class-D player that only a master (or a computer) would be able to refute, is that move really a mistake?

In the end, I think that both players in this game can hold their heads high. It wasn’t a masterpiece. It wasn’t even a flawed masterpiece. But it was good, exciting amateur chess, and at least the final combination is more or less sound.

Sam Landsberger — Dana Mackenzie, 2/18/1975

1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e5

I tried a lot of things against 1. d4 in my early years. I started with the Albin Counter Gambit. Too unsound. Then I tried the Queen’s Gambit Declined for a while, but it was just too hard to get a fun, open position. (The game I showed in my last post was a rare exception.) The Budapest was my third attempt, but I didn’t stick with it for very long either.

3. de Ne4

My temperament at the time was not to try to grovel to win back the pawn with 3. … Ng4, but rather to go for an “honest” pawn sacrifice.

4. Nf3 Nc6 5. e3 …

Okay but not the best. The real test is 5. a3, when I don’t think Black really gets compensation for his pawn.

5. … d6 6. ed Bxd6 7. Bd3? Nc5?!

Missing the opportunity for 7. … Bb4+!, when White has to move his king and lose the castling privilege. But an even more egregious mistake is yet to come!

8. O-O?? …

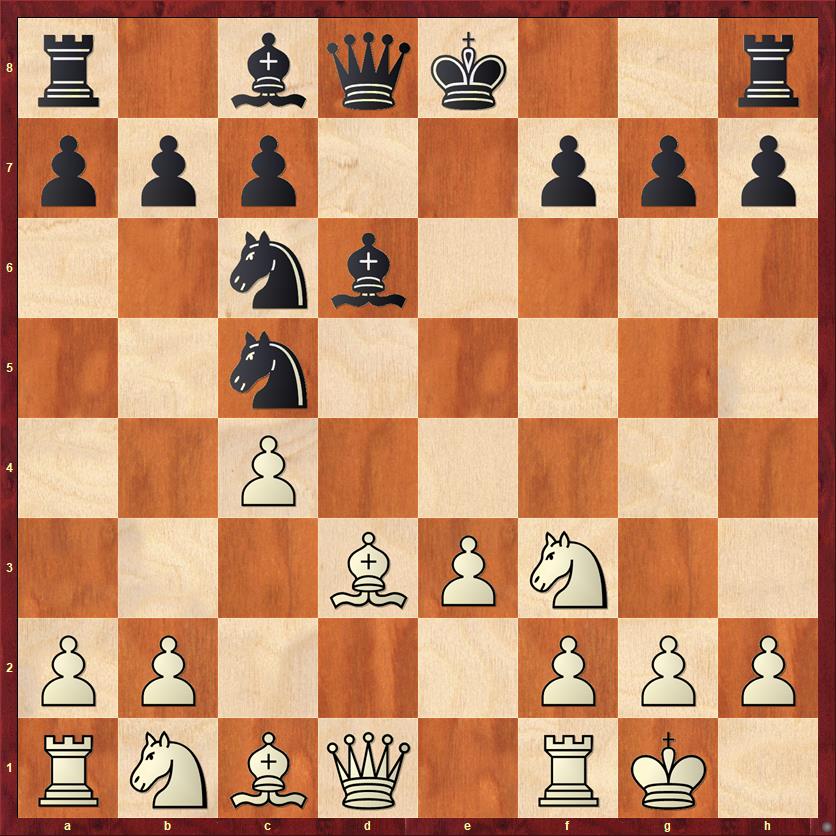

FEN: r1bqk2r/ppp2ppp/2nb4/2n5/2P5/3BPN2/PP3PPP/RNBQ1RK1 b kq – 0 8

Okay, girls and boys! Put on your elementary-cheapo hats and tell me what was wrong with White’s last move.

8. … Bg4??

Looking at it today, it took me one second to see that 8. … Nxd3 wins a piece, because 9. Qxd3? loses the queen to the discovery 9. … Bxh2+. This cheapo should be part of every chess player’s education. It was not part of my education yet, obviously.

But if I had seen the cheapo, then I probably would have won the game very easily, and then we wouldn’t be looking at it today.

9. Be2 h5? 10. h3? …

Avert your eyes, chess purists. We have a non-developing move for Black (9. … h5), followed by the only move for White that justifies my playing 9. … h5. This is reminiscent of Brian Wall’s “Fishing Pole,” where White never really threatens to take on g4 because he would get mated on the h-file.

10. … Qf6! 11. Nc3 O-O-O 12. Qc2 g5

Preparing to hide my queen on h6 or g7. Also, long-term, I have a plan of … Bxf3 followed by … g4.

13. Nd5 Qh6 14. Nd4 Bxe2

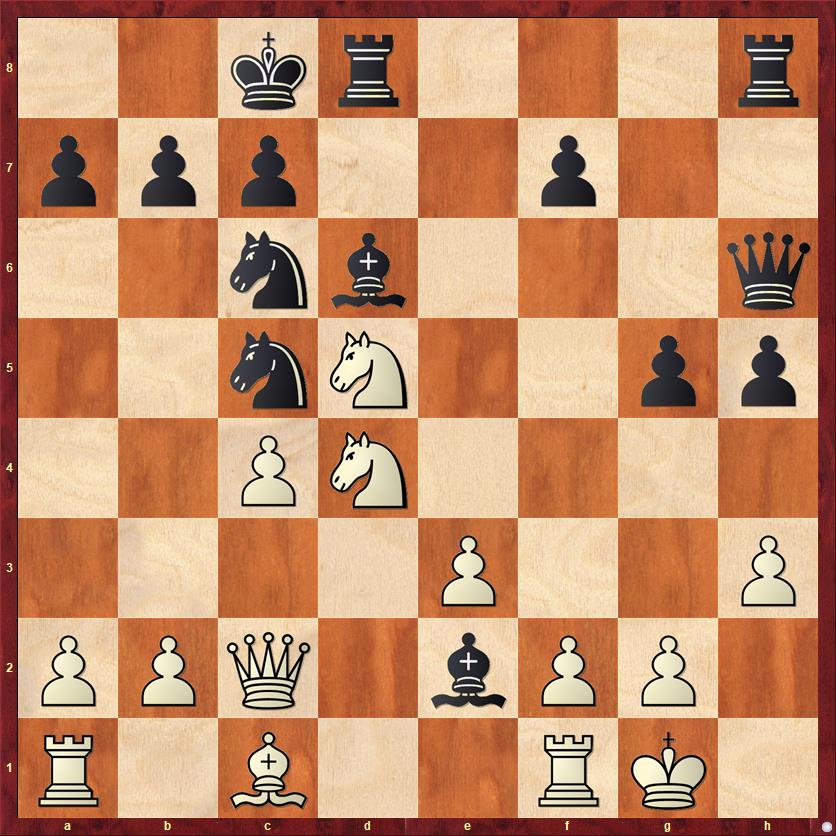

FEN: 2kr3r/ppp2p2/2nb3q/2nN2pp/2PN4/4P2P/PPQ1bPP1/R1B2RK1 w – – 0 15

Of course I was expecting 15. Nxe2, which might be followed by 15. … g4 with some nebulous compensation for the pawn for Black. But give credit to Sam — after his next move, the game starts getting seriously bonkers.

15. Nf5?! Qg6?

According to the computer, Black should call White’s bluff and play 15. … Bd3! 16. Nxh6 Bxc2 17. Nxf7 g4. I think I probably looked at this briefly, but rejected it because I didn’t want to trade queens. Young whippersnappers like me never want to trade queens — that’s “old man” chess. Also, White gets two pawns and a rook for two pieces. I did not realize yet that this is at best material equality, not a material advantage for White. And look at the position! Black’s pieces crawl all over the board, while White has only one active piece (the knight on d5) and everything else is either undeveloped or doing nothing. For these reasons, the computer gives Black a whopping two-pawn advantage (after 17. … g4).

To see all of this would take a wiser, more experienced player than I was at that age.

16. Nxd6+ Rxd6 17. Qxe2 Qg7?

FEN: 2k4r/ppp2pq1/2nr4/2nN2pp/2P5/4P2P/PP2QPP1/R1B2RK1 w – – 0 18

Another move that I thought was brilliant at the time, but Fritz shoots holes in it. My idea, of course, was to prevent b2-b4, which I saw as a threat, and also to get my queen away from the g6 square where it is vulnerable to a knight fork on e7. It also possibly sets up … Rg6 or … Rh6.

This is great! It shows admirable prophylactic thinking. It has multiple purposes. It’s creative and unexpected. And it worked — my move convinced Sam that he couldn’t play 18. b2-b4.

Everything about it is great, except for one thing: White can play 18. b4! Black’s “threat” is an illusion, because after 18. … Qxa1 19. Bb2 Qxa2 20. Ra1 Black’s queen is trapped. And don’t forget that at the end of all of this, Black still has two pieces hanging — the knight on c5 and the rook on h8. So it’s not a case where Black can hang on with two rooks against the queen. Black is just busted.

Both Sam, on move 18, and I on move 15, committed the “chess sin” of taking our opponent’s word for it. Never believe your opponent!

18. Rb1 g4 19. h4 Ne5

Man, at this point my eyes lit up like cartoon characters’ eyes with dollar signs. The Mike Splane Question (“How am I going to win this game?”) had not been invented yet, but I knew how I was going to win: knight check on f3 followed by checkmate.

20. Ne7+ …

Sam’s knights seem to be magnetically drawn to that forking square on f5!

20. … Kb8 21. Nf5 Qg6 22. Nxd6 …

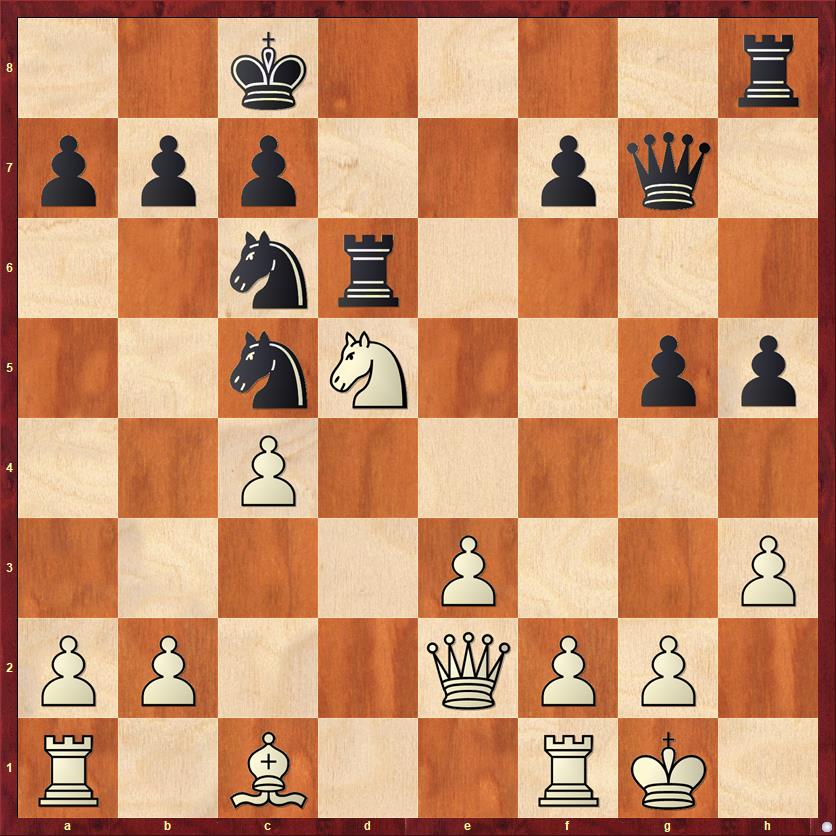

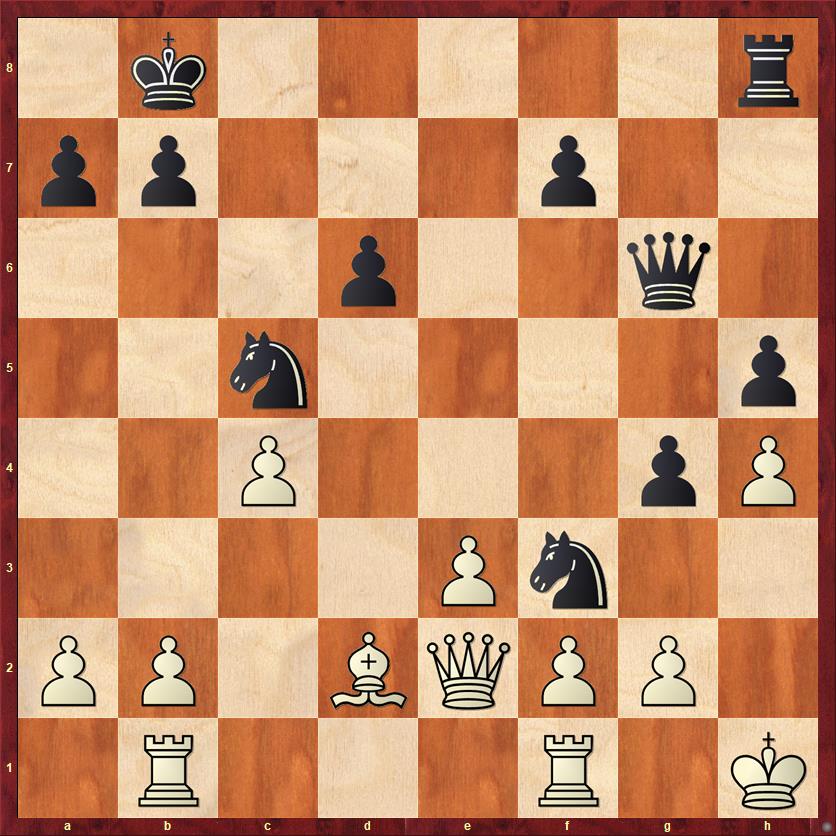

FEN: 1k5r/ppp2p2/3N2q1/2n1n2p/2P3pP/4P3/PP2QPP1/1RB2RK1 b – – 0 22

22. … cd?!

Once again, I play a move that I thought was a “brilliancy,” part of my “masterpiece,” but it is objectively inferior. Black just needs to play 22. … Qxb1. Simple chess. After 23. Nb5, then I can play 23. … Qxa2, finally winning my pawn back (remember that?) and also threatening the c4 pawn, which is hard for White to defend.

This shows the downside of being too attached to one answer to the Mike Splane Question. Don’t let it become such an idee fixe that it blinds you to other ways of winning the game. I was so sure I was going to win with a brilliant kingside attack that I didn’t properly consider moving my queen to the queenside.

Here’s another thing about 22. … cd that should have led me to question whether such a move could really be a “brilliancy.” In what concrete way does it help Black’s position? Aside from physically removing one White piece from the board it does not improve my position or help my attack in any way. You might say, “Yeah, but physically removing that knight is pretty good.” To which I respond that physically removing the rook on b1 would be even better.

But again, I don’t want to come down too hard on this move. I correctly judged that my threat of … Nf3+ was extremely dangerous. White needs to come up with a master-level defensive move here, and it’s no big surprise that he didn’t. So I’m giving 22. … cd a “?!” evaluation. The exclamation point is for the exuberance of youth, and the courage to play a very-nearly-sound exchange sac. The question mark is to acknowledge the sad reality that it isn’t quite sound.

23. Bd2?! …

Here the computer comes up with the excellent counter-sacrifice 23. e4!, which enables White’s bishop to play a much more active role in the defense. Active pieces are more important than material in this position! After 23. … Nxe4 24. Bf4 Nf3+ 25. Kh1 Qf6 26. g3 White’s defensive fortress is much stronger than in the game. Not only that, after 26. … Re8 27. Qd1 Nxh4 28. c5!, all of a sudden the security of Black’s king becomes an issue! This would be truly master-caliber play.

White’s move 23. Bd2 is perfectly sensible, mobilizing the last undeveloped piece, but it’s a little bit too slow. As I wrote correctly in my diary in 1975, from here on Black’s sacrifice is objectively sound, and in fact quite impressive.

23. … Nf3+ 24. Kh1 …

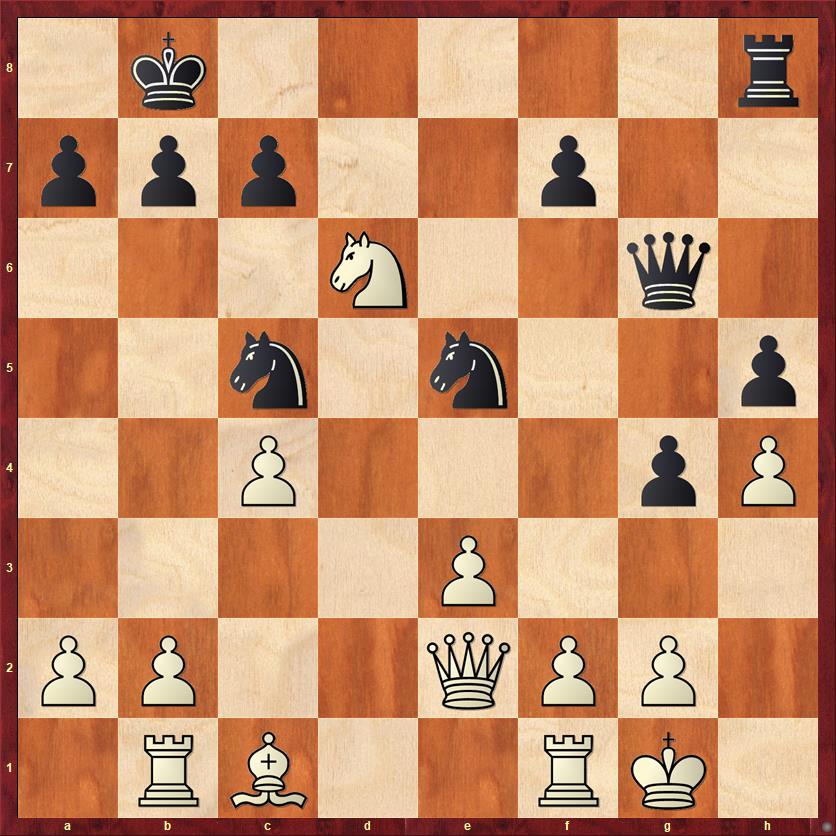

FEN: 1k5r/pp3p2/3p2q1/2n4p/2P3pP/4Pn2/PP1BQPP1/1R3R1K b – – 0 24

Now, what’s the followup?

Though the game was long ago and I don’t remember my thoughts exactly, I suspect that my original plan was to play 24. … Qf6. After 25. g3 Nxh4 (which I probably would have played) I couldn’t convince myself that I was winning. [For what it’s worth, the computer thinks that after 26. gh? Qxh4 I am winning, but if White plays instead 26. Bc3! he can weather the storm, with a slight advantage. Again, this is master-level defense.]

Then I realized that Black has a better move, which prevents both 25. g3 and 25. gf.

24. … Qe4!

This is probably my favorite move of the game, because it was a logical deduction from what I needed to accomplish. Now 25. g3 loses to either 25. … Nxh4+ or 25. … Nd4+.

25. fg? …

After this move the game ends swiftly. The “ingenious defense” that I mentioned in my diary, and did not see during the game, was 25. Bc3! Not only does White attack the rook on h8, but he also plans to bring his bishop to f6, where it protects the h-pawn. If that happens, Black won’t have much of an attack left.

This is where, in my two hours of study on February 28, I found a “spectacular refutation”: 25. Bc3! Qe7!! The rook is unimportant: what is paramount is getting the queen to h4. Now White has two ways to avoid checkmate:

(a) 26. fg Qxh4+ 27. Kg1 Rg8 28. f4 Ne4 29. any move g3 and Black wins. This is exactly the variation that I found in my two hours of analysis. It has all the relentlessness of an Alekhine combination: Black just keeps piling up threats until White’s position breaks. However, I like the next variation even better.

(b) 26. g3 Qe4!! Yes, that’s right! This little pas du basque where the queen goes to e4, leaves and comes back again, is the elegant point of the combination. White now has no way out of the discovered check, so he might as well grab the rook: 27. Bxh8. And now, after 27. … Nxh4+, White has to give all of the material back: 28. f3 gf 29. Rxf3 Nxf3. The knight, too, executes a pas du basque, going to f3, leaving, and coming back again with the same threats as before. If 30. Rd1 Qg4! 31. Qg2 Ne4 Black’s knights are just murderous. White best hope is to play 30. Rf1, where the computer gives a +0.8-pawn edge to Black after 30. … Nd2+ 31. Kh2 Nxf1+ 32. Qxf1 Qc2+ 33. Kg1 Qg6. I agree with this assessment, because the knight will come to e4 and be a dominating piece, and White’s king will be quite uncomfortable with the queen and knight loitering around.

I truly have no idea whether I would have found this idea of … Qe7 and … Qe4 if Sam had played the correct move, 25. Bc3. At least I did find it in my post-game analysis, without computer help (because chess computers did not yet exist).

After the move that Sam actually played, the game was over in a hurry.

25. … gf 26. Qd1 Qxh4+ 27. Kg1 Rg8 mate

Lessons:

- Don’t take your opponent’s word for it.

- Study your elementary cheapos, ideally by doing lots of puzzles. This is something that intermediate players (1200-1800) should work especially hard on. Above 1800 you might not get as many opportunities to play the cheapos, but you still need to see them and make use of them as threats.

- The Mike Splane Question (“How am I going to win this game?”) is an excellent way to order your thoughts, but it should not become an idee fixe. If a better way to win comes along, you should not hesitate to change plans. Generally speaking, masters are strong not so much because they see one way to win, but because they see a variety of possible wins.

- I think that some classic-games books do amateurs a disservice by presenting combinations, and especially sacrifices, as the highest value in chess, thereby promoting a sort of anti-materialism. This does have some instructional value, because it encourages amateurs to consider other factors than material. But a GM truly does not give a damn about sacrificing material for a “brilliant” combination. What he does is evaluate all the factors in a position, including material, and place them all in their proper balance. When the best way to win is to sacrifice material, he’ll do that. But when the best way is something else, even playing “ugly” chess, grabbing material and hanging on, he’ll do that too. A master must be unprejudiced.