Today we’re going to have a bit of deja deja vu vu: a game that I’ve already annotated once in my blog. It is still one of my favorites, and much more interesting than the other two games I have kept from 1977. But I will do it with one ground rule: I’m going to try not to repeat what I wrote before. This will be an interesting challenge!

Before we get to the chess, though, I have to mention one funny diary entry I came across, a few weeks after this game was played. On July 29, 1977, I wrote: “[At the dinner table,] Daddy asked me what I thought I’d be doing twenty years from now. Mommy immediately remarked that a couple nights earlier she had dreamed she asked that same question of me and some of her childhood friends, but the alarm clock woke her before they could answer. So she repeated the question for real, and Daddy buzzed his lips in a ridiculous parody of her imitation of her alarm clock. It turned out that we all agreed it was an impossible question to answer.”

Indeed, a kind of question that NEVER gets answered: by the time you get the answer, you’ve forgotten you ever asked the question. Certainly by the time July 29, 1997 rolled around, I had no memory of this conversation.

But we’ll see if I remember this time. When I get to 1997, which will be year 26 in this series of blog posts, I will tell you what I was doing on July 29. It was actually a pretty important transitional moment in my life. Not that particular day, but certainly that particular week. No spoilers!

Okay, now let’s get to the chess. As you remember, I had ended 1976 with a five-game winning streak and an 1838 rating, which put me in class A for the first time. In 1977, most of my rated games were played in the monthly Second Sunday Quads at Virginia Commonwealth University.

The summer got off to a great start, as I won my first quad 3-0, the first time I had ever done that. I optimistically wrote, “I will pick up something like 30 to 40 rating points, which makes it reasonable that I might be an Expert [2000] by the end of the summer!” Even more optimistically, I wrote, “My tournament chess winning streak is now, unbelievably, at eight games (my previous high was three). Eleven more and I’ll tie Fischer! Of course, he was playing masters.”

Well, you can see how good I was at predicting the future. I finally reached an expert rating 4 years later, not “by the end of the summer.” And my winning streak ended at eight. Fischer need not have lost any sleep over his record.

For the July 4 weekend I rode the bus up to Washington, DC, to stay with my grandparents and play in a tournament at the University of Maryland. While I was gone, the rest of my family went to see a new movie called Star Wars. “Sounds like fun!” I wrote. Because of this tournament, I didn’t watch Star Wars until the mid-1990s, when my nephews started getting into the whole saga and we watched it on DVD. Something I could never have dreamed of in 1977. At that time, I had no nephews and there was no such thing as a DVD!

Here’s what I did that weekend instead of watching Star Wars.

Dana Mackenzie — Geoffrey Wyatt, 7/3/1977

Note: If you want to see what I wrote about this game in my previous post (2016), follow this link.

1. e4 d5 2. ed Nf6 3. d4 Nxd5 4. Nf3 g6 5. Bc4 …

In my previous post I criticized this move, and I still do. Black’s setup is based on creating a strong point on d5. This move is too gentle to seriously challenge that plan. 5. c4 is the more principled move.

5. … Bg4

In my previous post I queried this and said, “This makes no sense whatsoever.” I take back what I said. Black apparently wanted a setup with all of his pawns on white squares. If that was his objective, it makes perfectly good sense to trade off the light-squared bishop first.

6. h3 Bxf3 7. Qxf3 c6 8. Nc3 e6

Completing his “Maginot line.” In the previous post I gave this a question mark too, because I did not like the dark-square weaknesses this move creates. I would never have played this move myself. But it is feasible, and Black’s worst mistakes really came later.

9. O-O! Bg7

Here Black had a couple of interesting alternatives. I think I was hoping he would try to win a pawn with 9. … Nb6 10. Bb3 Qxd4? Then I would win big material with 11. Bg5!, threatening both Bf6 and a “Morphy checkmate” with Rd1 and Rd8 mate. Also not good for him is 9. … Nxc3 10. bc Bg7, when he disrupts my pawn structure but gets his king stuck in the center after 11. Ba3! Both of these lines show very clearly the negative consequences to Black of 8. … e6, which weakened his dark squares. But as long as Black keeps his cool and doesn’t go pawn-grabbing, he should still be okay.

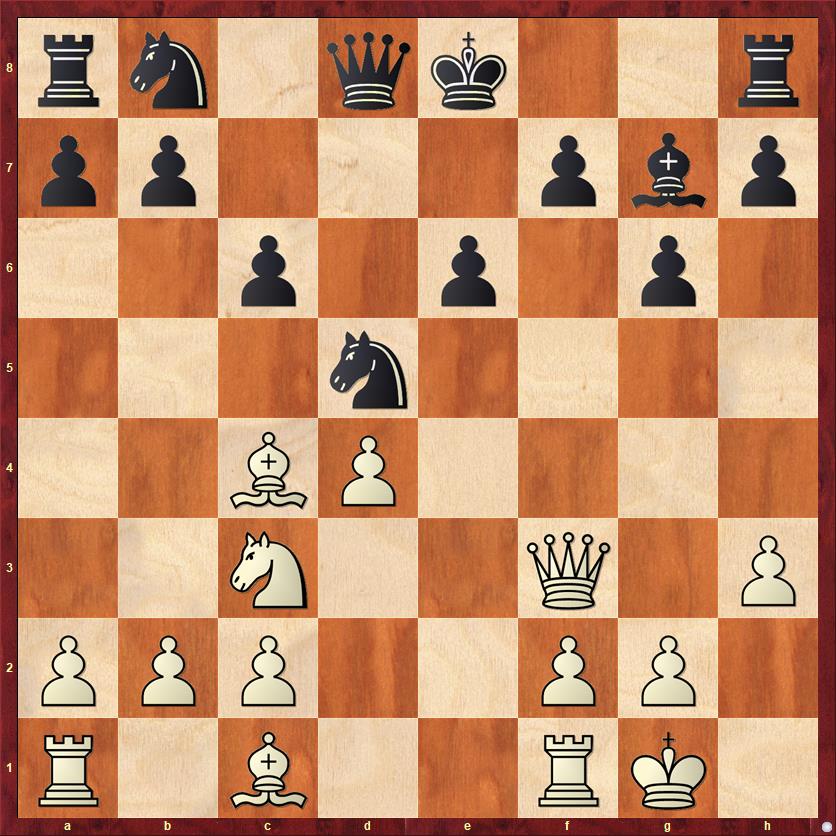

FEN: rn1qk2r/pp3pbp/2p1p1p1/3n4/2BP4/2N2Q1P/PPP2PP1/R1B2RK1 w kq – 0 10

This position is an interesting one, where younger-me and older-me would play quite differently. Younger-me was starting to get the idea of playing pawn sacrifices (as we saw on move 9) but I was still very nervous about them and not inclined to leave the pawn undefended for long. For that reason, younger-me played the nervous move

10. Rd1 …

Not a bad move at all, but there are two things I don’t like about it. First, it commits the king rook to d1 when it might be the queen rook that wants to go there. How is the queen rook going to get in the game now? Second, it gives Black another chance to trade on c3, which I’m not sure I want to allow. Older-me prefers 10. Ne4!, a much more dynamic move that increases the pressure on the dark squares. It also dangles that d-pawn in front of Black a little bit longer: “Here, come and get me!” In my previous post I wrote that 10. … Bxd4? 11. Bh6 prevents Black from castling. Fritz, however, finds a much more concrete refutation: 10. … Bxd4? 11. Rd1! (Now this move is good, because the rook will be an attacker rather than a defender.) 11. … Bg7 12. Bg5! (Black’s difficulties on the dark squares mount. 12. … f6? 13. Bxf6 exploits the pin on the d-file.) 12. … Qc7 13. Bxd5! cd 14. Nf6+. This turns out to be unexpectedly crushing, because 14. … Kf8 runs into the hard-to-see 15. Qa3+! Qe7 16. Nxf7+ winning Black’s’ queen.

It’s interesting that the move that seems right to me on general principles, 10. Ne4, also has such a powerful tactical kick to it. But it rests on finding the rather computer-like move 15. Qa3+. I didn’t see any of this in 1977, and I didn’t even see it the first time I annotated this game in my blog!

10. … O-O 11. Ne4 …

Finally getting around to playing this natural move. All is right again with the world.

11. … h6 12. Qg3?! …

In my previous post I wrote a very long tirade about why this was a bad move. I still agree with most of it, but I promised not to repeat myself! So I’ll say that the one good thing about this move is that I’m trying to put pressure on the dark squares. But the trouble is that Black can (and should) just go about his business with 12. … Nbd7. If White jumps into d6 with his knight, it accomplishes absolutely nothing after 13. Nd6 Qc7.

12. … Ne7?

However, I will not cut my opponent any slack. This terrible move is what starts his position sliding downhill and eventually costs him the game. Here are all the things wrong with it: 1) Black ignores rule number one of the opening, which is to develop your pieces. 12. … Nbd7 should be almost automatic. 2) Black moves an already-developed piece. More than that, on d5 it is his best piece and helps in the battle for the dark squares because it discourages Bf4. Black wastes two tempi to transfer it to a square (f5) that is not as good. 3) I think that Black is being lured by the siren song of material. The reason he wanted to move to f5 is that he has ideas of winning my d-pawn. But this is, as Mike Splane sometimes says, playing a middlegame idea when it’s still the opening.

In my previous post I wrote a lot about “moving your pretty pieces,” which is a great concept from Jesse Kraai. His point was that chess amateurs always like to move their best-developed and most active pieces (like the knight on d5) because they can do more things. But a few moves later, we discover to our dismay that we’ve moved our best pieces around, not really made them any better, and meanwhile our ugly pieces are still languishing and doing nothing.

13. Bf4 Nf5 14. Qh2! …

The queen is not “pretty” at all here, but she is quite effective.

14. … Qb6?

Continuing to neglect development in order to chase a pawn.

15. c3 …

A forced pawn sacrifice, but a good one.

15. … Na6

Black finally completes his “development,” but on a6 the knight is practically as undeveloped as it was before. I’m sure that Black did not feel that it was safe to play 15. … Nbd7 16. Bc7 Qxb2. In truth (and I’ll use the computer as the arbiter of truth) it is rather hard for White to actually trap Black’s queen.

By not taking the poisoned pawn, Black gets the worst of both worlds. He gets a position with wretched piece coordination, and he doesn’t even have a pawn to show for it.

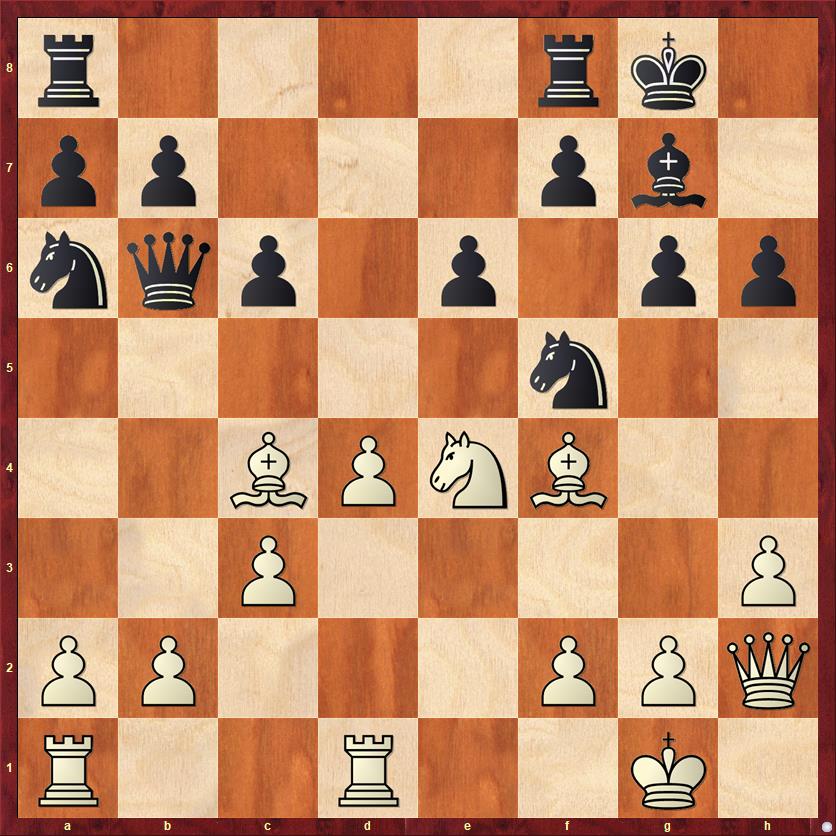

FEN: r4rk1/pp3pb1/nqp1p1pp/5n2/2BPNB2/2P4P/PP3PPQ/R2R2K1 w – – 0 16

Now I play another nervous move.

16. b3? …

Another move that shows a big difference between younger-me and older-me. What I hate about this move is that it shows such a passive mindset in a position where I have the advantage. I should be the one making my opponent worry, not the other way around.

Of course, we all have to make passive/defensive moves now and then. But whenever possible, you should find a way to accomplish something else at the same time: defend your weakness in a way that makes a threat, or that gives you some other kind of advantage.

Let’s suppose that … Qxb2 is really a threat I need to worry about. I don’t know if it is, but let’s suppose so. Isn’t there a way to prevent … Qxb2 and improve my position in some other way? How about Rd2? Or — my favorite — how about just pushing the b-pawn one step farther? With 16. b4! I not only prevent … Qxb2, I also (and probably more importantly) shut down the pawn break … c5, which is almost the only way he can bring some life to his position. Note also that after 16. b4! I do not need to worry about 16. … Nxb4?? because 17. Bc7 this time traps the queen for real. (Perhaps I overlooked this?)

16. … g5?

Black should have tried 16. … c5. A strange thing about this game is that every time I played a dubious move, my opponent played one that was even more dubious. The result is that my dubious moves actually looked good, and I missed some learning opportunities. A moral is that you should look at your won games with just as critical an eye as your lost games.

17. Be5 Qd8 18. Bxg7 Kxg7?

He had to swallow his pride and play 18. … Nxg7. Now the White queen re-enters the game and she’s got only one thing on her mind.

19. Qe5+ Kg6

Have I mentioned the dark squares at all? With Black’s dark-square bishop eliminated, Black’s other pieces have to protect f6 — including his monarch, who is not well suited to such duties.

20. Bd3! …

Finally my bishop leaves c4, where it never belonged in the first place, and finds a much more effective diagonal… one with the hostile king on it. And the king can’t get away, either. Always a pleasant set of circumstances.

20. … f6

Clearly a desperate move. But, as I explained in my previous post, even non-desperate moves like 20. … Qd5 or 20. … Ne7 lose very quickly.

21. Qxe6 Nc7

A slightly better try was 21. … Re8, when the ensuing sacrifice is still sound but would have required more careful calculation.

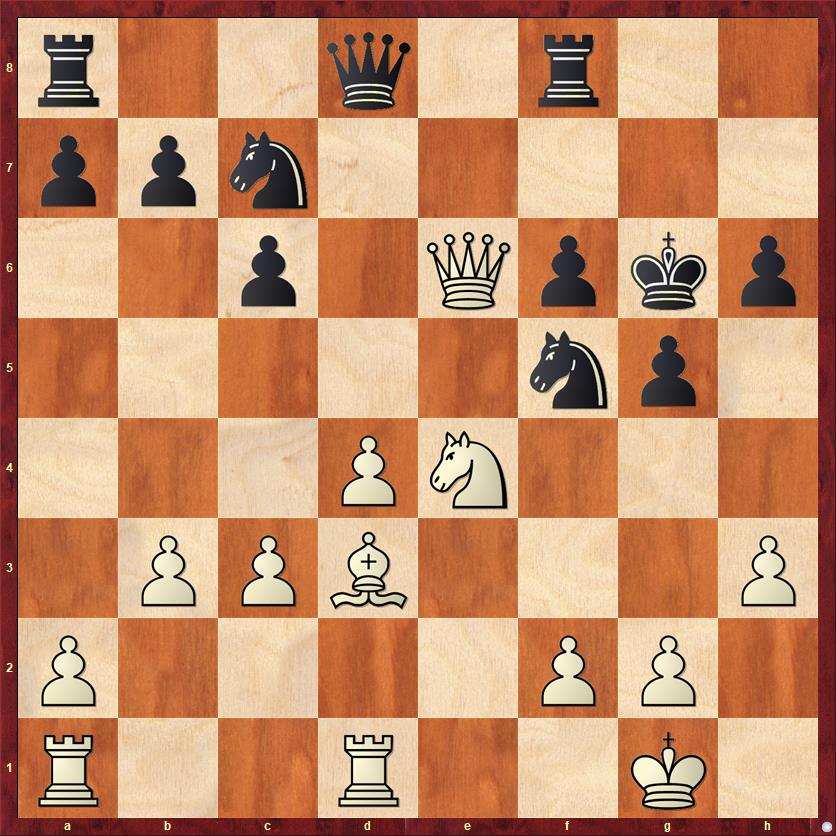

FEN: r2q1r2/ppn5/2p1Qpkp/5np1/3PN3/1PPB3P/P4PP1/R2R2K1 w – – 0 22

And now comes the moment we’ve all been waiting for!

22. Qxf5+! …

My first queen sacrifice ever in a tournament game, and a really nice one. Like Edward Lasker versus Sir George Thomas, it features a queen sac followed by a king hunt deep into White’s position. It’s not quite of the same caliber as Lasker-Thomas, of course, but there is at least a faint resemblance.

22. … Kxf5 23. Nc5+ Black resigns

After 23. … Kf4 24. g3+ Kf3 White has lots of ways to win. I probably would have played 25. Bf1 with the unstoppable threat of Rd3 mate.

In my previous post about this game, I did not mention how White would have won after 21. … Re8 (instead of 21. … Nc7). In that case, after 22. Qxf5+! Kxf5 23. Nc5+ Kf4 24. g3+ Kf3 25. Bf1 Nxc5! poses some annoying problems for White. On 26. Bg2+ Black’s king slips away to e2. Of course, 26. Rd3+ is no longer possible because the knight controls d3. On 26. dc Black would be only too happy to give up his queen for the rook and reach a favorable endgame with 26. … Qxd1. Do you see how White can claim the full point?

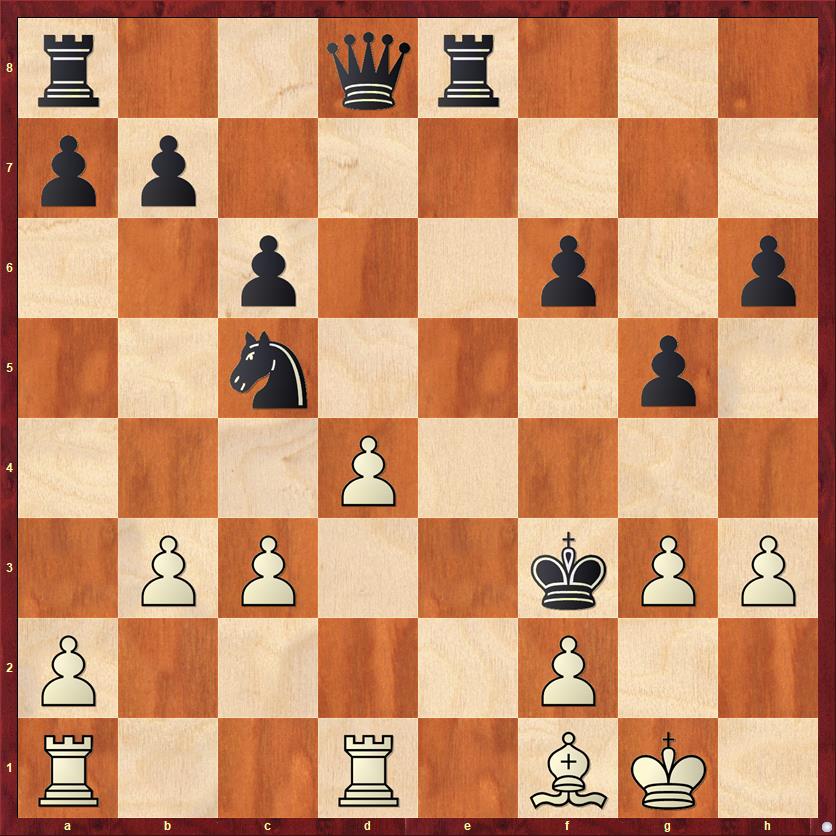

FEN: r2qr3/pp6/2p2p1p/2n3p1/3P4/1PP2kPP/P4P2/R2R1BK1 w – – 0 26

A little space added in case you want to think about it …

The solution is the exquisite

26. Re1!! …

This quiet move controls both of the flight squares for Black’s king, e2 and e4. Black can trade rooks but aside from that he has no way to postpone Bg2 mate.

I just love the last two moves of this combination, the ultra-quiet moves Bf1 and Re1. They are quieter than the footsteps of a mouse hiding from an owl in a snowstorm in Siberia. It’s amazing that Black is a full queen up (well, for a pawn) and yet he still can’t get his king out of the mating net.

Lessons:

- In a king hunt, you will often get better results if, instead of checking the king all around the board, you play one (or two!) quiet move(s) that close the mating net.

- Develop your pieces!

- More generally, resist the urge to make all of your moves with your “pretty pieces.” Make a conscious effort to make your “ugly pieces” less ugly and give them a role in the game.

- Avoid purely defensive moves. Always try to find moves that do at least two things at once.

- Watch out for the “Maginot line” pawn formation e6-f7-g6-h7. Like the real Maginot line, it’s full of holes. If your fianchettoed bishop gets traded or lured out of position, the game can get ugly in a hurry.

- Given a choice of playing a chess game or watching a movie, play the chess game.

Trivia Question: In what sport was Sir George Thomas more famous (and more successful) than in chess?

Answer: In chess, Thomas is known primarily for his brilliant loss to Edward Lasker, in a game that wasn’t even an official tournament game. He did, however, have some major accomplishments. He was a two-time British champion and had a sensational tournament in Hastings, 1934/5, where he defeated former world champion Capablanca and future world champion Botvinnik in their individual games, and tied for first with about-to-become world champion Euwe. You could argue that Capablanca was “no longer Capablanca” and Botvinnik was “not yet Botvinnik,” but still… what a tournament!

Nevertheless, Thomas was an even greater legend in badminton, where he won the British championship 21 times (four times in singles, 17 in mens’ and mixed doubles). He also played in the Wimbledon tennis tournament in 1911 and reached the quarterfinals.