A colder and wetter moon?

Wednesday, July 22nd, 2009

Yesterday I went to the Lunar Science Forum at Ames Research Center, which was the scientists’ version of a Moon Fest – a chance for all the recent and current moon missions to unveil their latest and greatest findings. According to the organizers, more than 500 people registered, including 200 just since last Friday. I don’t think that all these people actually came — the main meeting room holds 300, and it was not filled to capacity. Nevertheless, it was a well-attended (and well-Twittered) event.

Yesterday the science teams of the LRO and LCROSS missions, which just launched last month, presented their data publicly for the first time. As David Morrison, the head of the Lunar Science Institute, said in his introductory remarks, “Last year most of the papers reported plans, but I’m delighted to say that most of the talks this year are about results.”

All of the LRO results are very preliminary, because LRO is still in its “commissioning orbit,” when they are still warming up and checking out the systems. By the way, I mean warming up quite literally. Most of the instruments have residual moisture in them from their time on Earth. (So do most tourists, after a few hours in the humidity of south Florida!) So they have to go through a “bake-out” period to dry out all of that extra moisture. The LRO camera finished its bake-out on July 10, but even before then (as mentioned in this entry) it started sending back fabulous pictures.

Also, scientists from two other moon missions spoke yesterday. There was one presentation on the Japanese Kaguya mission that just ended a week before LRO lifted off, and three about the Indian Chandrayaan-1 mission that is still ongoing.

The most interesting news yesterday all had to do with results that we can’t really talk about yet! One of them is so preliminary that no one can really interpret it yet. The other two are results that are going to be published soon but are currently under “embargo,” meaning that the scientists aren’t supposed to talk about them until the publications come out.

First, David Paige, principal investigator for LRO’s Diviner experiment, showed some of Diviner’s first measures of the temperatures in the moon’s permanently shadowed craters. Remember that these are supposed to be “cold traps,” where water molecules could perhaps accumulate as ice because they are too cold to float away. The first temperature readings in Amundsen crater turned out to be even lower than expected: around 33 degrees Kelvin (or 33 degrees above absolute zero).

No one had predicted such a low temperature; I think that 70 degrees Kelvin was closer to what they had expected. As Paige said, “If this is true, it’s colder than the poles of Pluto!”

From his wording, you might correctly infer that Paige is not really sure this measurement is right. The instrument has been calibrated, but he said there are some possible reasons why the instrument-measured temperature may not be the same as the physical temperature. (For example, they don’t really know what kind of surface they are looking at — rocky or soft and fluffy — and that can make a difference to how they estimate the temperature.) The instrument is still too fresh and new, and the finding too unexpected, to put a lot of stock in it yet. But what it could mean is that the permanently shadowed craters are a better cold trap than we thought.

Two other surprising results that can’t be talked about yet came out of the Chandrayaan-1 mission. Carle Pieters of Brown University reported on the Moon Mineralogy Mapper, and said that her team had made a new discovery on lunar volatiles that she can’t discuss yet. Of course, the most important potential ”lunar volatile” is water. But, she said, “Don’t give me wine and try to dig the secret out of me.”

Then Paul Spudis, whose Once and Future Moon blog is always thought-provoking, talked about the results from his mini-SAR (synthetic aperture radar) experiment, which is also on the Indian Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft. Like Pieters, he has a result that he can’t talk about yet, but he said, “I may be susceptible to being plied with drinks!”

Mini-SAR is also looking for water ice; the idea is that ice will reflect a circularly polarized radar beam differently from rocks. (The radar wave will actually go into the ice before bouncing back, because ice is transparent.) This is similar to the way that ice was first detected at the south pole, by the Clementine mission in 1994; Spudis was the deputy leader of the Clementine science team. However, the Clementine satellite only got one brief peek at the south pole, and so its results were very ambiguous. You can’t do very much in science with one data point. Chandrayaan-1 should do much better. We will have to wait to find out just how much better it’s done.

Nevertheless, I will transcribe a fascinating exchange that occurred during the audience-questions period after Spudis’ talk. Clive Neal, the chair of NASA’s Lunar Exploration Analysis Group (which advises NASA on the choice of moon missions) went to the microphone.

NEAL: You said there were some things that you cannot talk about, but then you proceeded to talk about some of them… (Laughter from audience.)

SPUDIS: You don’t know that! (Laughter.) You’re making an assumption, and maybe it’s warranted, maybe it isn’t.

NEAL: So I’ll ask my question as delicately as I can. You showed data that seemed to be consistent with the presence of water ice on the moon. Would you care to comment on that? (Loud laughter.)

SPUDIS. No! (Laughter.) But you’re welcome to draw whatever conclusions you care to.

NEAL: Can I just rephrase the question? If I buy you a beer, would you comment?

SPUDIS: It depends on what kind of beer and how much. (Laughter.)

DAVID MORRISON: I think all of us are beginning to assume that in a month or two we’ll have a wetter moon than we do now.

SPUDIS: Well, the moon isn’t going to change. (Laughter and applause.) Our perceptions might change. But, you know, some of us have had this perception for a long time.

Make of it what you will! Just don’t blame me for breaking any embargoes.

Other tidbits and factoids from the first day of the meeting:

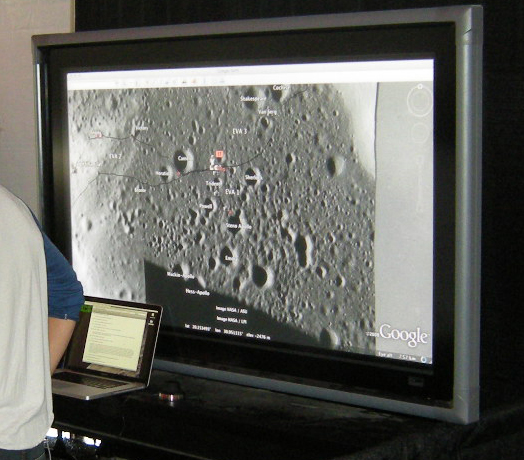

These roads are so confusing.

- Google released its new version of Google Moon on Monday, and there was a large screen in the tent demonstrating it. It’s a huge improvement over the previous map-based Google Moon. This one has all the latest imagery from the LRO mission, and will continue to be updated constantly — so look for it to continue improving by leaps and bounds over the next year.

- The LRO launch was perfect, and that is very good news for the scientists, because it means that there is more fuel left for an extended mission than they could previously count on. Craig Tooley said that this could extend the life of the mission by a year. (The spacecraft has a planned one-year life span, followed by a two-year extended science mission. I interpret Tooley’s remarks to mean that it could continue orbiting for a fourth year.) I would think that the extra time would be especially valuable for the narrow-angle camera, which can only image about 10 percent of the moon in any given year.

- I asked Sam Lawrence, of the LRO camera team, whether they had felt under any pressure to get the pictures of the Apollo landing sites out early. He said, “I won’t lie to you. Several people in Headquarters simultaneously and independently came up with the idea of taking pictures of the Apollo landing sites. But Isaac Newton is in the driver’s seat. It was largely serendipity that we happened to be in the right place to image them.” In fact, the Apollo 12 landing site has not been imaged yet, but it should come around into the camera’s view in a couple of weeks.

- There was lots of Twittering going on at this conference. I sat behind someone whose laptop had a screen full of twitters. I have so far refused to get on twitter.com, but those of you who are might want to check out what the scientists are twittering about.

- Yes, there is such a thing as a free lunch! Registration for this conference was free (which is already unusual for a scientific meeting) and the Lunar Science Institute provided the lunch and refreshments free of charge, too! Shhh… Don’t tell Washington that they’re using your tax money to feed starving scientists …