“That’s Daddy’s rocket!”

Tuesday, August 25th, 2009

In an earlier post I wrote about the LCROSS mission, which is due to make its crash landing on the moon on October 9. (Mark your calendars!) In July I talked with Tony Colaprete, the Principal Investigator for the mission. I apologize if there is a bit of unevenness in this interview, because I have cobbled it together from three sources — our conversation at the Moon Fest, an e-mail, and his presentation at the Lunar Science Forum. Answers have been edited for length but I have tried to preserve Tony’s wording.

Tony Colaprete (NASA photo)

DM: You told me that you were born the week before the Apollo 11 landing. So, happy birthday! How big an inspiration have the Apollo missions been to you?

TC: I was born July 16, 1969, the day Apollo 11 launched. My father was heavily involved in the Apollo program, and one of my early childhood gifts was the classic Snoopy dressed in an EVA suit. So, yes, the Apollo mission was a huge influence, not only because they were so amazing but also because of my father’s involvement. … I am amazed to think that the folks who did Apollo were on average around 25 to 27 years old! The commitment, devotion, and guts those people had is inspiring. I just hope I can do things half as right as they did for the Apollo program.

DM: When and how did you decide that you wanted a career in space exploration? How did you prepare for it?

TC: When I graduated from high school I knew I wanted to either go into the sciences or art. Luckily for us all, I decided to go into the sciences. … Very early on, though, I loved being in the woods near Boulder, Colorado, where I grew up. I would go for hours by myself and just watch what went on around me. So very early on I knew I loved systems, how things work together and influence each other … I still do.

I worked on instrumentation at the University of Colorado through the Space Grant College and the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics for a few years after getting my bachelors degree in physics. I was taking a few graduate classes (including my first planetary atmospheres class, taught by a very inspiring David Grinspoon), when I realized I wanted to pursue a graduate degree in planetary sciences. Luckily, CU is a great place to do that!

While I was doing my graduate work I continued to work on instrumentation for sounding rockets, space shuttle flights, and small spacecraft. This combination of science and engineering (again, systems!) was key, I think, to helping me get where I am now.

DM: How did the idea for the LCROSS mission come about?

TC: When LRO moved up to a bigger rocket, they had room for an extra 1000 kilograms on board, and a call for proposals went out for a co-manifested mission. And by the way, they said, you have only 2½ years to get it done, and you can’t spend more than $80 million.

When the call was announced, we [at NASA Ames] formed a “Tiger Team” to come up with ideas. Early on in the process we considered an impact mission, but I concluded that with only 1000 kilograms to work with, the impactor mass would be too small.

Another person in the group, Geoff Briggs, suggested using the spent upper stage of the launch vehicle. He has since said that he got the idea from someplace else. I ran some numbers and convinced myself that an impact by an object of about 2000 kilograms would produce a cloud observable from earth.

At about the same time, Northrop Grumman submitted a [proposal] that was also using the upper stage and also had a small shepherding satellite that could make observations. An engineer on the Tiger Team saw the idea and told me about it. We had a couple Northrop Grumman scientists come up and we discussed our ideas and the rest was history. So I don’t think it was any one person’s idea, but just enough people with the same idea!

In the end, LCROSS was selected out of 17 proposals. We cheated the 1000 kilogram limit — it’s 3200 kilograms, because we held on to the spent Centaur [rocket stage], which is about 2300 kilograms.

DM: Have you ever watched a launch in person before? If so, how was it different, knowing that it’s your own experiment that is going up?

TC: I’ve flown payloads on sounding rockets and shuttle flights, and have seen those go before. This Atlas moved so slow at first! I thought to myself, “You’d better pick up some speed or you’re not going to make it!” The sounding rockets and the shuttle use solid fuel, whereas the Atlas V is all liquid — it’s a big difference!

My biggest concern at launch was whether we could get off on the 17th or the 18th [of June], because those two days result in very good impact observing conditions for the continental U.S. The 19th was not so good, and on the 20th [there were no good times] at all. So I was very glad the weather broke in time for us to go on June 18.

DM: Have there been any exciting moments since the launch?

TC: I held my breath when we turned on the instruments for the first time. That was a moment of sheer terror and anxiety for me. Also, I’ll hold my breath again on August 1, when we turn them back on. Radiation and vacuum can have effects on detectors, so they always degrade over time. Once we know that they are working, I will be very confident that the payload will survive until the impact with the moon. [According to the mission page, the checkout of the infrared cameras and spectrometers on August 1 went very well. They took spectra of Earth and -- stop presses! -- detected oxygen, water, and vegetation! -- DM]

DM: What are you expecting to see when LCROSS hits the moon?

TC: There are a couple different models of how the water gets to the south pole and two different predictions for how it is distributed. We describe them as the smooth versus chunky models. In the smooth model, the ice is uniformly distributed on the scale of this room, with about a 1 percent concentration of ice. If that model is correct, LCROSS will have very good chances of detecting it. LCROSS should be sensitive down to concentrations of half a percent.

However, if the ice is chunky, with smaller pockets of up to 10 percent ice, then we might have a 10 percent chance of hitting something. If we hit one of the “peanuts” in the chunky peanut butter, we’ll know. This would immediately distinguish between the two competing models.

My biggest fear is that we won’t see anything — that it will be a dud. But even in that case, then we’ve learned that the distribution isn’t smooth. That is important to know, because it means that your next mission [i.e., a lander to search for ice on the ground -- DM] had better be mobile.

DM: How does the LCROSS mission compare with other spacecraft that have crash-landed on the moon (Lunar Prospector, the European SMART-1, and the Japanese Kaguya)?

TC: None of those other missions were designed as impactors. The biggest difference is that they typically hit the moon at a low, grazing angle, because they were in orbit around the moon. LCROSS is not, it’s in orbit around the Earth. [This is a rather non-obvious fact that is illustrated on the flight director's blog at this link. LCROSS doesn't "go to the moon." It goes into an orbit around Earth that is the size of the moon's orbit, and then the moon just runs into it! - DM] So it will hit at a very steep angle, around 85 degrees. Also, we’re bringing quite a bit of mass. So those missions can’t be compared to LCROSS for visibility, size, and impact angle.

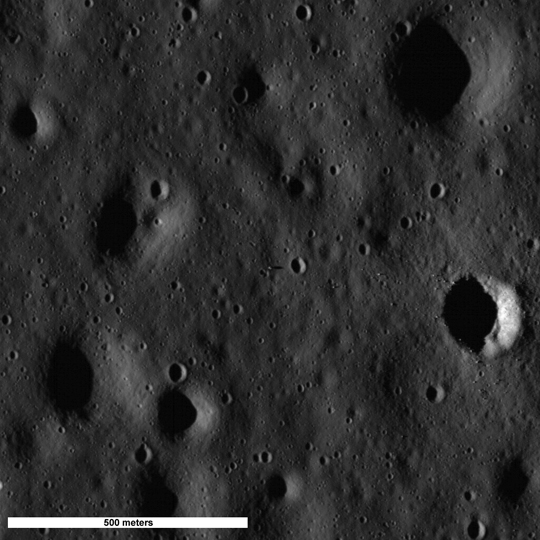

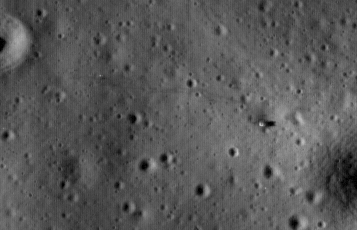

DM: How big a crater will the LCROSS impact make?

TC: We’ve done simulations using Apollo-era technology, and we expect the crater to be about 20 meters wide — the size of a tennis court. We expect the plume to contain about 300 to 400 metric tons of material.

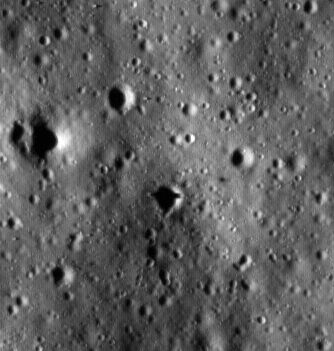

DM: On the LCROSS website you have a list of several possible target craters. Do you have a favorite on this list?

TC: Faustini would be my preference. It’s a very old, large crater, so the material in there has been in shadow for a very long time — around two and a half billion years. We want to hit somewhere that is flat and fluffy, not blocky and steep. One thing against it is that it’s right on the limb of the moon. So the ejecta have to go up 2 kilometers in order to be illuminated by the sun. In some of the other target craters, the ejecta only have to go up about 500 meters. But for earth observers, a position on the limb means that you get high contrast [against the darkness of space -- DM], and that’s good.

DM: I think it’s interesting how you have been able to use the results of other recent missions to narrow down the list of targets for this mission. Can you talk a little bit about the synergy between missions, and especially the Japanese Kaguya spacecraft?

TC: The topography from their laser altimeter has been invaluable. First, it lets us calculate the slope of the ground. You don’t want to hit a slope [because you would then lose the benefit of a high impact angle -- DM]. Kaguya also gave us amazing information on the depth of the craters. Some of the errors in the previous estimates were significant, on the order of 500 meters to a kilometer. From the Kaguya terrain camera we got information on the surface roughness and albedo [reflectivity] of the craters. So, overall, they matured our current data set.

Also, with new LRO data coming online, we’ll be refining our numbers continuously to make the wisest choice of target. We will finally make an impact site selection by 30 days before impact, roughly the first week of September.

DM: How can ordinary people contribute to the LCROSS mission?

TC: Amateurs have already contributed, and with an impact with the moon high and the skies dark as far east as Texas, I hope many more will continue to contribute.

One thing to realize is that professional astronomers typically don’t point their telescopes at the moon. To most of them, the moon is a source of light pollution. So when we asked the best in the world to look at the moon for a change, there was a steep learning curve. One thing they needed to learn was how to find the crater you want to point to amongst a hundred or so other craters that look very similar. The shadows and bright areas change dramatically with small changes in the sun angle, so finding one’s way around the moon can be difficult if one has never looked before. To help, we asked the amateur community to image the moon at all phases and tilts so that we had a library of sorts for the various light conditions.

During the impact, amateurs with a minimum of about a 10-12 inch telescope can observe the impact. We will be soliciting these observations and will share them with others. [There is a Google Group for amateur observers at this link -- DM.]

DM: Finally, do your kids know that “Dad is a rocket scientist”? If so, are they proud of it, and are they paying any attention to the LCROSS mission?

TC: I have a son who is two and a half and a daughter who is five years old. They came to the launch, and when they look at the moon now they say, “Daddy’s rocket is flying to the moon!” After the launch my wife and children took a different flight home than I did. During the layover, on one of the cable news channels playing at the gate, they showed a replay of the launch. My children both yelled, “Daddy’s rocket!” My wife says that the people around them looked with a bit of a skeptical stare until she said, “Actually, it is their daddy’s rocket.”