Round six of the Tuesday Night Marathon at the Mechanics Institute was another hard-fought draw. I really don’t mind draws, even against lower-rated players, as long as good chess was played on both sides. In this game, my opponent made a really strange mistake on move 7 and I thought that the game might just be an easy win for me. But after that he hung in there and didn’t make any obvious mistakes. Although I had a slight plus most of the way, I didn’t quite find the moves to put the most pressure on him — perhaps erring too much on the side of caution.

Here are two missed opportunities and a not-missed opportunity.

Missed Opportunity 1.

Position after 9. Bc4. Black to move.

FEN: rnb1kb1r/pp3ppp/2p5/4P3/2B1n3/8/PP3PPP/R1BNK1NR b KQkq – 0 9

I’m Black, playing against James Wonsever, a class-A player. After the game he complained that I played a “sketchy” opening, but he played a way-more-than-sketchy response. It went 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 Nf6!? (the “sketchy” Marshall Defense) 3. cd Nxd5 4. e4 Nf6 5. Nc3 e5! (This is one of the main points of the Marshall. White’s overeager response runs headlong into this unexpected shot. Wonsever, surprised by the turn of events, overreacts.) 6. Bb5+ c6 (Wonsever told me after the game that he simply forgot that Black had this move. For a little while I thought I was just winning a pawn, but he does have a way out.) 7. de Qxd1+ 8. Nxd1 Nxe4 9. Bc4 … And we have arrived at the position above.

What should Black do in a position like this, where White has very obviously screwed up? There are two schools of thought. One is to play calm developing moves and wait for him to screw up some more. The other is to put forth a maximum effort to “punish” him.

With 20-20 hindsight, I think that punishing would have worked better in this position. I like the idea of 9. … b5! chasing the bishop to a worse square, and trying in the sequel to win a bishop for knight. The most consequential variation, I think, is 9. … b5 10. Bb3 Bb4+ 11. Ke2 Nc5! (This looks dangerous because the knight on c5 and the bishop, which will soon be on a5, can be forked.) 12. Bc2 Be6! 13. a3?! (Probably 13. b3 is better, but it looks as if White is winning a piece with this move. But he’s not.) 13. … Bc4+! 14. Ke3 Ba5 15. b4 Nb3! 16. Bxb3 Bb6+! gaining a tempo to get out of the fork. Note that 14. Kf3 would not have saved White either because of 14. … Ne6 threatening … Nd4+.

To me this is a very Alekhine-esque variation, using Black’s slight edge in development and White’s exposed king. But it has to be calculated very carefully. In particular, what I missed was the idea of … Be6 followed by the check on c4, forcing White’s king to take his pick between two bad squares. The other problem with playing this way is that if I mess up, the positional consequences could be bad, because I have messed up my queenside pawn structure with … b5, making the c6 pawn much more of a target.

Instead I played the more Capablanca-esque 9. … Bb4+ 10. Ke2 Be7 11. f3 Nc5 12. a3 a5 13. Be3 Be6 14. Bxe6 Nxe6. But I feel as if I have missed my chance to put White under more pressure. As more pieces get traded, his king gets more and more comfortable in the center. The long-term consequences of his gaffe on move 6 have become almost nonexistent.

Missed Opportunity 2.

Position after 31. Nd2. Black to move.

FEN: 8/1p3k2/2p2bpp/p2r4/1P2RPP1/P6P/2KN4/8 b – – 0 31

You can’t make a move if you don’t even think about it. In this position I was starting to get a bit low on time — 20 minutes for the rest of the game — and I thought I would save time on the clock by playing a quick “automatic” pawn capture, 31. … ba?!

There is no such thing as an automatic pawn capture in chess, and I should at least have taken a look at the much more dangerous move, 31. … a4!

Even without looking at any variations, this must be better for Black because:

- According to the principle of two weaknesses, Black needs to create two weaknesses in White’s camp to win. In fact, there are several: a3, h3 and f4 are all weak.

- You can argue, of course, that after the trade of pawns on b4, White’s b4 pawn is a weakness. But a second factor of great importance is that in a B-vs.-N endgame, the weaknesses should be spread out as much as possible. It is much harder for White to defend a pawn on a3 and a pawn on f4 than it is to defend a pawn on b4 and a pawn on f4.

- In many endgames (for example, if we should get to a K+P endgame) Black has a threat of playing … b5, followed by … c5, … b4, and … a3 running the a-pawn. Or if the B and N stay on the board, it is much harder for the knight to stop an a-pawn than a b-pawn, as we will see.

- Finally, if nothing else, … a4 makes sense because it takes b3 away from White’s knight, and if White plays 32. Nc4 then 32. … b5 will take away the c4 square as well. B-vs.-N endgames are all about taking away squares from the knight.

I’m not sure whether you can actually say that 31. … a4 is winning, but it puts a lot more pressure on White.

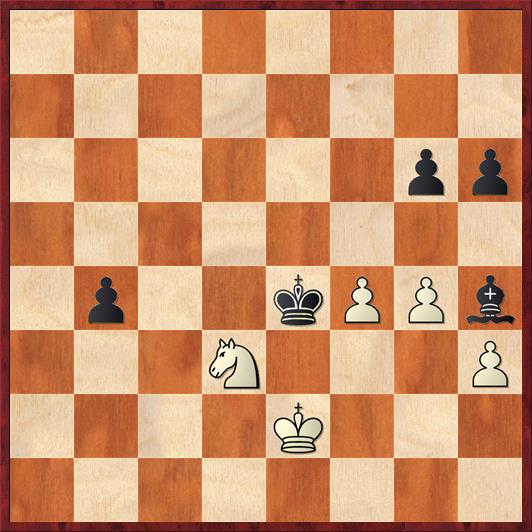

Not a Missed Opportunity

Position after 49. Nd3. Black to move.

FEN: 8/8/6pp/8/1p2kPPb/3N3P/4K3/8 b – – 0 49

Here it looks as if Black has made a lot of progress and may even be winning, but in fact White has a simple and concrete drawing method: trade off Black’s g-pawn (even at the cost of a pawn), then sacrifice the knight for the b-pawn. So after my move, 49. … Be7 50. f5! gf (unfortunately, Black cannot decline the trade) 51. gf Kxf5 52. Nxb4! we immediately agreed to a draw.

After the game my opponent wondered if I should have played 51. … b3, but now 52. f6! Bf8 (52. … Bxf6 53. Nc5+ draws immediately) 53. f7 establishes the f-pawn as a very credible threat. For example, 53. … Kd4 54. Kd2 h5 55. Nf4 Bh6 (seemingly a winner but…) 56. f8Q! turns the tables. After 56. … Bxf8 57. Ne6+ now it’s Black who has to scramble to draw.

Also, 49. … b3 right away would lead to a draw after 50. Nc5+ Kxf4 51. Nxb3 Kg3 52. Nd4. Although Black can win the h-pawn any time he pleases, he will not be able to break through White’s defenses after … Kxh3 Kf3.

These lines show how much easier it is for White’s knight to cope with a b-pawn than an a-pawn. Put a White pawn on a3 and Black pawns on a4 and b5 and the position would be hopeless for White. This shows the long-range consequences of my decision to simplify on move 31.

Missed Opportunity 3.

The day before this game, I went to Church’s Chicken for a fast-food dinner. There were two customers before me: a man with a clearly homeless look about him sitting in the corner, and a woman who was waiting for two meals. She was badgering the cashier about making sure that both meals had the requisite items — make sure this one gets a biscuit and that one gets a fruit pie. They were having a hard time communicating because the cashier had a very thick Indian accent.

Finally, I figured out that the two meals she was buying were for herself and the homeless man, whom she referred to as “that young man” even though he looked to be 40 or 50 years old and perhaps not any younger than her. I figured this out because she said that she wanted to give “that young man” his meal, then go home and turn on the TV.

I have given homeless people a quarter now and then, and maybe even in my most generous mood I’ve given them a dollar. But I would never have thought of buying a seven- or eight-dollar dinner for a homeless man, and watching to make sure that he got every biscuit that I had paid for. In fact, I would not even have called him “that young man.” To me, he was “that homeless man in the corner whom I want to avoid making any contact with.”

I wish I had demonstrated enough presence of mind to tell the woman how I admired her act of charity. Even more, I wish I had offered to split the cost with her. I feel as if it would have increased the total amount of fellowship in the world. But I didn’t think of “the winning move” until later.