Here’s a game that I wrote about last fall, but didn’t have a chance to analyze until yesterday. I do eventually analyze all of my tournament games, but sometimes it takes a few months (or years) for me to get to them!

My opponent in this game was Luke Harmon-Vellotti, who was (is?) the highest-rated 9-year-old in the country. It’s very interesting and even a little bit scary, because he really outplayed me strategically but then lost because of a tactical oversight. Usually when you play against a prodigy, it’s the other way around: kids are more dangerous at tactics, but don’t have as good a sense of strategic play. However, we may be looking at a new kind of prodigy here. Recently I wrote a post about David Adelberg, an 11-year-old who (according to David Pruess) has the strategic sense of a young Karpov. Maybe Harmon-Vellotti is another positionally-minded youngster.

Before I forget, here is the PGN (with a tip of the hat to Chad).

Luke Harmon-Vellotti — Dana Mackenzie

Western States Open, 2008

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nd4 4. Ba4 …

In my series on the Bird Variation, this is the one thing I haven’t gotten to yet — what I call the “Bashful Bishop Variation,” when White retreats to a4 or c4 instead of trading knights on d4. The concept of 4. Ba4 is similar to the Rubinstein Variation of the Two Knights Defense. However, because Black has not yet played … Nf6, he has another setup at his disposal which, in my opinion, gives effortless equality.

4. … Nxf3 5. Qxf3 Qf6!

This is the idea. It’s not that Black wants an early queen trade; really, his main point is to establish control over d4 and also neutralize the influence of White’s queen. It would be a bad idea for White to trade queens with 6. Qxf6 Nxf6, because he gives up a tempo, and it will now be almost as if the players had switched colors. If White doesn’t want a queen trade (and most White players won’t) then he has to lose a tempo moving his queen somewhere else.

6. Qe3 b6 7. O-O Bc5 8. Qe2 Ne7 9. d3 O-O 10. Be3 d6 11. Nc3 Be6 12. Bb3 …

So far both sides have basically been developing their pieces. Now I made a decision that strongly affected the course of the game. It wasn’t necessarily a mistake, but I wish I had thought out its consequences more seriously.

12. … Bxb3

I was very focused on trying to prevent his knight from coming to d5, and that is the reason behind my next two moves. However, is it such a bad thing if his knight goes to d5? For example, if I play 12. … Qg6, then I would actually be happy to see him play 13. Nd5?! because I would play 13. … Bxd5! (a favorable bishop-for-knight trade in this position) 14. ed Bxe3 15. fe (or 15. Qxe3) f5. White has shut in his bishop, and Black’s knight is the better minor piece. Not only that, Black has attacking chances on the kingside.

I’m not sure that 12. … Qg6 is best either (13. f4 seems like White’s best response), but this does show that my focus on d5 was a little bit misguided.

13. ab Qe6 14. Bxc5! …

One of several good judgements by my young opponent. This is a perfect time to trade the bishops. Black doesn’t want to take with the b-pawn, as that would leave the a-pawn isolated and forever weak. But taking with the d-pawn has its drawbacks, too. It means Black can no longer get a pawn lever with … d5, and also the pawn break … f5 becomes harder to accomplish because the e5 pawn will be weak.

14. … dc 15. Rfe1 c6?!

Weakening the queenside and taking a possible square away from the knight. Notice that Black had many, many opportunities to play the prophylactic move … a5. Now would have been a good time.

16. Qe3 Ng6 17. Kh1 …

I kind of thought White was drifting here, but actually he is building towards a possible f2-f4 break. Now I played a very impetuous and stupid move. I think this lunge is partly explained by psychological factors. My lower-rated opponent is not making any threats, and so I felt it was my duty to seize the initiative.

17. … Nf4?

A general rule of thumb for knight play: Don’t move your knights into your opponent’s half of the board unless (1) they cannot be driven back or (2) they have a better square to retreat to than the one they have just vacated. It would have been better to play 17. … Qd7 first. After that, … Nf4 would be a real threat because of rule 2 (the knight has a nice square on e6 to retreat to). From e6, the knight would threaten to come to d4, which would be a good square because of rule 1 (the knight is hard for White to drive away).

18. g3 Nh3

I guess I was thinking I could whip up some sort of threats against his king, but with only a queen and a knight, this “attack” doesn’t have a prayer of getting anywhere.

19. f4! …

Seizing the initiative. Now Black’s knight on the rim is in trouble.

19. … Qh6

20. f5! …

Once again, excellent judgement for a 9-year-old (or any age). White is not tempted to “win a pawn” with 20. fe because after 20. … Qxe3 21. Rxe3 Nf2+ 22. Kg2 Ng4 23. R3e1 Nxe5 Black wins the pawn back and gets his knight to a very nice square.

20. … Qxe3 21. Rxe3 g5

Now 21. … Nf2+ doesn’t look so appealing, because after 22. Kg2 Ng4 23. R3e1 a5 24. h3 Nf6 25. g4 White is starting to get an attack going on the kingside. It’s not the end of the world for Black, and with queens off the board Black has good chances of drawing, but still Black has a purely defensive position. My move tries to “mix it up” a little.

22. Ra6 …

This was one of those “oh crap” moments, when it suddenly dawned on me that I had really screwed up. I had so many chances to play … a5, but now it’s too late. It is very difficult now to defend the a-pawn against his slow-motion attack with Re1 and R1a1. At this point I thought for about 20 minutes, leaving myself only 22 minutes to play the remaining 18 moves until the time control.

A couple of good lessons here:

1) Relax! It isn’t as bad as you think it is. Here, in fact, there is nothing wrong with 22. … Nf2+ 23. Kg2 Ng4 24. Re1 Rfb8 25. h3 Nf6 26. Rea1 Rb7. White has a little pull, but so far Black has only one weakness, and one weakness shouldn’t be enough to lose the game.

2) The moves you take the most time on are often your worst ones. In this case, in spite of thinking for 20 minutes, I missed two key points in the above line. First, I had an irrational loathing for the move 24. … Rfb8. It seemed so passive to me. But sometimes, especially if you have made a mistake, you will have to play passive or even “ugly” moves. You just have to be realistic about your position and swallow your pride. Second, I missed the fact that White has to play 25. h3 before 26. Rea1, because otherwise Black’s … Ne3+ would be too strong. But the move 25. h3 gives Black the extra tempo he needs to get the knight back to the queenside and successfully defend the a- and b-pawns.

Why did I miss this? I think that I was still too much under the grip of my emotions. The point about White having to give Black an extra tempo is a subtlety, and subtleties are the first thing that you miss when you’re thinking with your emotions instead of your brain.

So here I played what should have been the losing move:

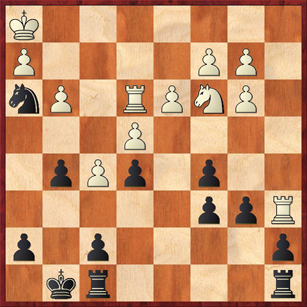

22. … g4? 23. Re1 Ng5 24. Rea1 Nf3

White to play and win (or anyway, get a big advantage).

Now is when the game started to turn. Black’s idea is obvious: he wants to bring the knight to d4 and put pressure on the c2 and b3 pawns. White does not want to allow this. If White can find a way to defend the queenside pawns — especially c2 — then Black will be helpless to prevent him from winning a pawn on the queenside. That was why 22. … g4 was a mistake — I staked all of my hopes on counterattack, and if the counterattack doesn’t work then I’m just losing material.

The move IÂ worried about most during the game was 25. Na4? However, this move works out fine for Black after 25. … Nd4 26. Nxb6 Nxc2 (there is no point in trying to save the rook with 26. … Rad8?) 27. Nxa8 Nxa1 28. Rxa7 Nxb3 29. Nb5 f6!

The move that Harmon-Vellotti played was also a mistake, albeit a very plausible one.

25. Ne2? …

A logical move, very consistent with the patient approach White has shown throughout the game. Seeing that the immediate attack with 25. Na4 is premature, he plays a prophylactic move. But he picks the wrong one! The correct move was 25. Nd1!, which is very strong because after 25. … Nd4 26. Ne3 White has defended c2 and Black cannot defend a7. Not only that, White’s knight is also eyeing both the g4 pawn and the c4 square. I don’t think I even looked at 25. Nd1 during the game, because it seemed to allow 25. … Ne1. But that is complete nonsense, because again 26. Ne3 holds everything, and the knight on e1 has to leave.

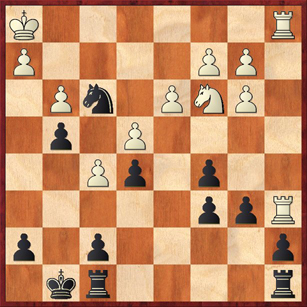

After the text move, Black’s position is once again defensible.

25. … Rfd8?!

As I commented before, 25. … Rfb8 is really the right approach. After 26. Kg2 with the idea of h3 followed by Kf2, White would complete his prophylaxis and be ready to take on a7 (or b6 if Black plays … Rd7). To stop this, Black will sooner or later have to play … Rfb8 and … Rb7. Better sooner than later.

Now, after 25 moves of playing with the calm and restraint of a seasoned master, my opponent plays his only rash move of the game.

26. Rxa7?? Rxa7 27. Rxa7 Ne1!

It’s amazing how this one move completely changes the complexion of the game. Although White drew first blood with his capture on a7, it is Black who will strike the fatal blows. White will lose all of his queenside pawns. It is especially noteworthy how ineffective his knight is on e2. Compare that to how strong it would have been on e3!

By the way, Harmon-Vellotti told me after the game that he simply didn’t see … Ne1. So his mistake on move 26 was not really a loss of patience; it was just a blind spot.

Here is how the game ended:

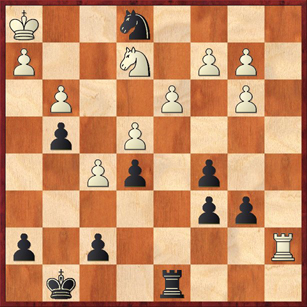

28. Rb7 Nxc2 29. Rxb6 Nb4!

This multipurpose move defends the c6 pawn and also cuts the rook off from the defense of the queenside pawns. In this position Black’s knight is the equal of White’s rook, while Black’s rook is a million times stronger than White’s lame steed on e2.

30. f6 …

Here or on the next move White should have played Nc3 with the idea of Na4 and Nxc5, in order to create some complications and get his knight into the game. As you will see, the knight remained on e2 for the rest of the game, doing nothing but getting in the way of his other pieces.

30. … h5 31. Kg2 Rxd3 32. Rb8+ Kh7 33. Re8 Rd2! 34. Kf2 Rxb2 35. Ke3 Nc2+ 36. Kd3 Ne1+ 37. Ke3 Rxb3+ 38. Kf2 Nd3+ 39. Kf1 Rb1+

When you’re low on time it’s nice to be able to play so many checks!Â

40. Kg2 Rb2 41. Kf1 Kg6 42. Rc8 Nb4 43. Rh8 c4 44. Rd8 Rb3 45. Rd1 c3 46. Rc1 c2

All three of White’s pieces are now paralyzed.

47. Ke1 Nd3+ 48. Kd2 Nxc1 49. Nxc1 Rf3 50. resigns

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

Hi Dana-

I just finished going through your game…and I have a question, as I don’t fully understand a position. In your variation at move 4: 4…Nf6 5. d3 Bc5 6. Nxe5 – why hang the pawn? Is it because you’re looking to get quicker development by playing Bc5 and then Qe7, which is worth more than a pawn?

Good advice regarding the Knight! (move 17).

Hi Chad,

You should think of the notes in the PGN files as a “first draft.” In some cases they represent what the computer thinks is the best line. In other cases they may be things I was wondering — what if …? The comments in my blog post are the things I have written after taking into account both the computer analysis and my own analysis, and therefore they should be taken more seriously than the PGN notes. (Of course, they can still be wrong!)

Now, to answer your specific question, I was interested in comparing the 4. Ba4 line to the other “Bashful Bishop” line, where White plays 4. Bc4. Here I think that 4. … Nf6 is the best move, with the plan of playing … d5 as in the Two Knights. Here Black is offering the e5 pawn, but White should probably not take it — after 5. Nxe5?! d5 or 5. … Qe7 Black gets a lot of counterplay against White’s center. And after 5. d3 Black can, if he wants, continue to offer the pawn sacrifice and get rapid development with 5. … Bc5.

So the main point of this annotation in the PGN was to reinforce in my mind the difference between the 4. Bc4 variation and the 4. Ba4 variation. In the 4. Ba4 variation I think it is dubious for Black to sacrifice the e5-pawn, precisely because Black cannot play the key move … d5. Black may get a little compensation in the form of more rapid development, but he doesn’t have enough concrete threats.

This is all stuff that I will probably say again when I finally get around to writing a full post on the Bashful Bishop subvariations.

This is uncannily similar to a tournament I played in a couple of years ago. It was the American Open and I had a disasterous tournament (3/8…ugh). In round 6 I was paired against Danil Fedunov, who at the time was either the highest rated or second highest rated 9-year-old in the United States. Both of our ratings were somewhere in the 1900’s at the time and I expected a tough battle.

In a similar way to you, Dana, I found that he was very sharp tactically but perhaps lacked some positional nous. I played a line as white against the French (I forget the name of the line… it involves white saccing a pawn on g5 and playing Nh3 to harass black’s queen). I had never played this line before, only seen it in a couple of published games, but I felt he would be unfamiliar with it and might underestimate white’s compensation for the pawn. Sure enough, I ended up with a terrific position and should have won the game. But then I missed one or two tactical shots and suddenly he was back in the game and we ended up agreeing to a draw. It was certainly a case of a kid not being quite so positionally savvy but finding great tactics when the going got tough.

It’s always a nervy thing to have to play a kid, especially when he/she is the “highest rated so-and-so in this category in the country”! I remember him being very nice and polite and it was fun to go over the game with him afterwards.

{ 1 trackback }