As we move forward through the years, we come to an unexpectedly sad entry. It’s not that 1973 was a bad year. Quite the opposite! It was a great year, in which I played four tournaments, won three trophies, scored 14-6 (close to my best year ever), and advanced one rating class, from class D to class C.

Also, 1973 was the only year when my father played in tournaments with me. Of course, he was the person who taught me chess, so it was an ironic reversal that by now I was the leader and he was the follower. I wrote in my diary things like, “Really, he must think faster if he expects to improve.” We played in three tournaments together. While I was winning class-D prizes, he was winning unrated prizes. It was a great arrangement, since we didn’t have to compete with each other.

However, after that year he didn’t continue in tournament chess. He said it was too stressful, and I can believe that. The game had only ever been a hobby for him, and he was quite good for a hobbyist. But unlike me, he was forty years old and had much more important things going on in his life. Improving at chess was not high on his agenda.

By 1973 I was also studying at a new high school — Phillips Academy (also known as Andover), a boarding school in Massachusetts. In my sophomore year I was the #1 chess player in the school, but in my junior year we got a “ringer,” a one-year senior named Kevin Toon.

By now I was class-C, but Kevin was class-A, with a rating in the 1900s. He was the first really serious player whom I got to know well. He subscribed to Chess Informant, a publication I had never heard of. He kept a card catalogue of grandmaster games in his openings. I’m not sure of this, but he might have been the scholastic champion of his state (Minnesota) before getting a scholarship to Phillips Academy.

Of course he won most of the games we played against each other, but it was a great learning experience for me to play regularly against a 1900 player, and moreover one who had a very calm, solid, positional style. It was an approach to chess that was new to me. Rarely could I ever provoke him to make a weakness that I could attack, and vice versa, he knew how to exploit the many weaknesses I created.

As I got ready to write this post, I wondered, “What ever became of Kevin Toon?” So of course I googled him, and I was stunned to see that he died in 2016, at the age of sixty. That’s the sad part of this post.

When Kevin was at Phillips Academy I had the sense that he was torn between chess, his past love, and philosophy, his new love, and that he would probably go in the direction of philosophy. And so he did, majoring in philosophy in college. But he did continue to play chess, and he eventually became a National Master before leaving the tournament scene for good after 1988. I don’t know what his peak rating was because he was before the era when USCF ratings went online.

But even after he was no longer playing, he didn’t lose his interest in chess! In 2013 he self-published a novel called The Death of Dr. Alekhine. Of course, as soon as I read about this I had to buy a copy (only $3 via Kindle).

Short review: It’s a murder mystery with world chess champion Alexander Alekhine as the victim. I’m afraid that I’m not a big fan of murder mysteries, and this one was less interesting to me than a good chess problem would have been.

Kevin did one thing in this book that makes it different from an ordinary murder mystery. After twelve chapters, Kevin’s detective has already solved the case, although he does not see fit to enlighten the reader about the solution. The next twelve chapters are just straight history of the Second World War, which apparently Kevin thought we would need to know to understand the solution to the murder. Then the last three chapters tie up the murder of Alexander Alekhine in a rather perfunctory way. I have to say that the part of the book I enjoyed the most was not the fifteen chapters of murder mystery, but the twelve chapters of history!

I have to wonder whether the last two lines of the book were autobiographical. They go as follows:

“You are a philosopher, sir.”

“Not at all,” said Detective Inspector Jacques Colbert. “Merely a logician.”

Was Kevin writing about himself? He wanted to be a philosopher, but he found that he couldn’t make a career of it, and ended up doing computer programming, which must have seemed to him like an inferior occupation. And then he wrote his Great Chess Novel, and then he died. It all seems too little, somehow.

Sigh.

Here’s a game against Kevin from 1973, one of two games that I won from him that school year. I selected this chess club game to annotate, rather than any of my tournament games, because this is the first game of mine that looks like real chess.

Dana Mackenzie – Kevin Toon, 10/5/1973

1. d4 c6 2. e4 d5

The positional, bend-but-don’t-break Caro-Kann Defense was a perfect opening for Kevin.

3. Nd2 g6 4. Ngf3 Bg7 5. c4 …

By contrast, I am always trying to muddy the waters. But this move leaves the d-pawn a little bit weak.

5. … de 6. Nxe4 Bg4 7. Be3 Bxf3?!

A slight misjudgement. Black gives away the two bishops and doesn’t really get anything in return. Perhaps he didn’t really believe that I would sacrifice my d-pawn.

8. Qxf3! …

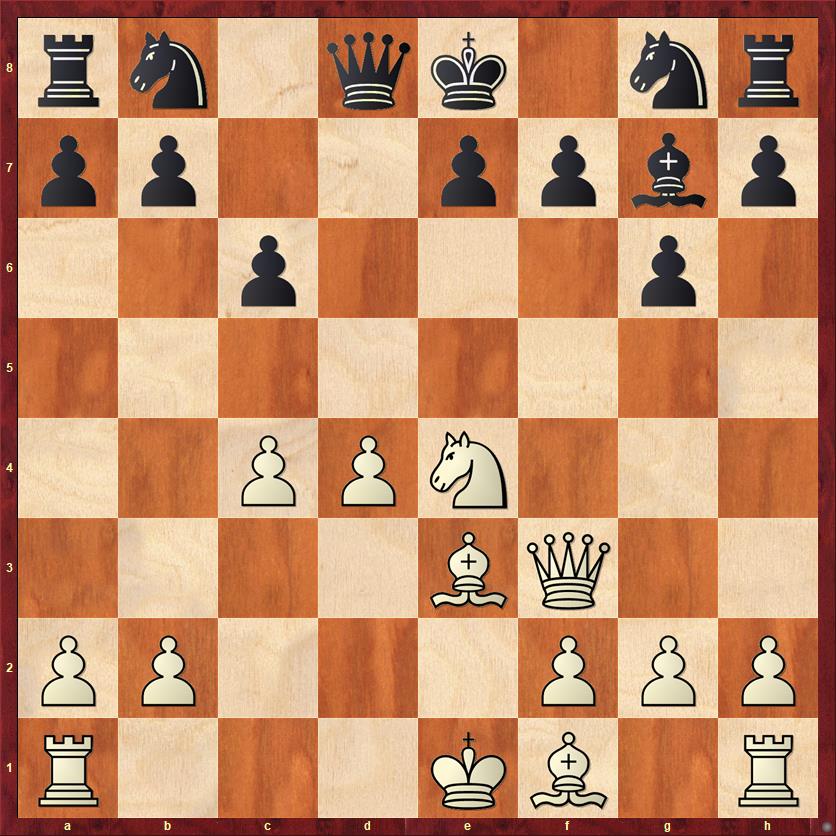

FEN: rn1qk1nr/pp2ppbp/2p3p1/8/2PPN3/4BQ2/PP3PPP/R3KB1R b KQkq – 0 8

Is the sacrifice sound? Should Black take the d-pawn?

8. … Nd7

Kevin declines the pawn, and wisely so. After 8. … Bxd4 would follow 9. O-O-O Bxe3 10. Qxe3, and now 11. Nd6+ can’t be prevented. Actually, after 10. … Nd7 the computer prefers 11. c5!, tying Black in knots because he can’t move either knight. But I can 100 percent guarantee you that I would not have played 11. c5, I would have played 11. Nd6+.

Quite reasonably, Kevin decides that losing the castling privilege would be too great a concession, and so he continues with a calm developing move. White has a slight advantage but it’s nothing overwhelming yet. On the other hand, I think that there is a psychological lift from playing a move that your opponent clearly didn’t expect — there’s a sense of “Okay, maybe this will be the time that I will actually beat him.”

9. Be2 …

I had to make a big decision: castle queenside or castle kingside? I opted for greater safety, really the only time this game that I did so. The main thing that bothers me about this move is the way that White’s pieces are clumped together and getting in each other’s way. Imagine putting a rook on the e-file (the only semi-open file). I would have to clear three of my own pieces out of its way to generate any threats! Nevertheless, that does eventually happen.

9. … h5 10. O-O Nh6 11. Rad1 Nf5 12. d5!? …

Wow. A very committing move. Another pawn sac, but Black can’t take it because of 12. … Bxb2? 13. dc bc 14. Nc5, hitting the pinned knight. I’m playing with a lot of energy, which I like, but I may have underestimated Kevin’s reply.

12. … Ne5 13. Qh3 Qc7 14. Bf4 ...

This position is like a powder keg ready to explode.

14. … c5! 15. Qc3 Nd4

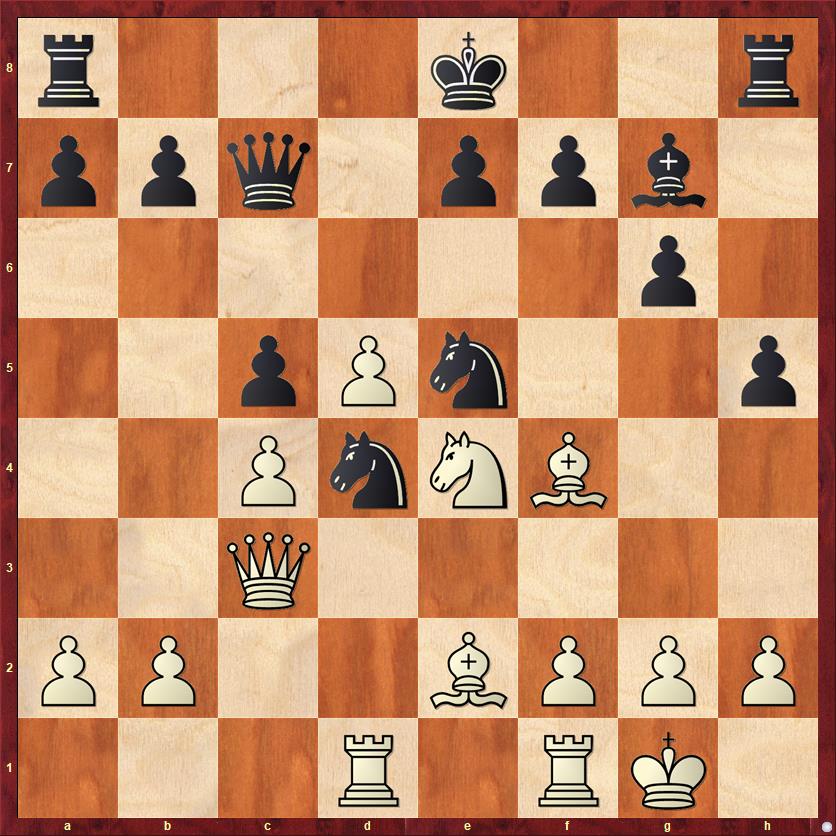

FEN: r3k2r/ppq1ppb1/6p1/2pPn2p/2PnNB2/2Q5/PP2BPPP/3R1RK1 w kq – 0 16

Black is getting some serious threats. Not only 16. … Nxe2, obviously, but also 16. … Nef3+ is threatened. How can White deal with all of this?

16. Rxd4!? …

In my own annotations I confidently gave this an exclamation point. But the computer points out a better option: 16. Qe3! This move defends both threats, keeps the question open about how exactly Black is going to escape the pin on the e5 knight, and doesn’t sacrifice the exchange. The move I selected does the first two things but does sacrifice the exchange (for a pawn). In the cold logic of the computer, that makes the move 16. Qe3 half a pawn better.

Be that as it may, I think there’s a lot to like about the move I did play. It gets rid of Black’s best piece and gives me a lot of activity. It creates a position where the pressure is going to be on Black to find good moves. It continues the theme of material for pressure and is a good, ambitious sequel to my moves 8 and 12. This time, obviously, Kevin can’t decline my sacrifice. He won’t be able to get a dry, technical, maneuvering game; he’ll have to fight it out. This is already a partial victory for me.

16. … cd 17. Qxd4 O-O 18. Qe3 Qa5

Kevin takes his opportunity to break the pin, but the computer says 18. … Qb6 would have been a better way. In fact, my move was also an inaccuracy; I should have played 18. Qc3, planning to play Qg3 next and not letting Black break the pin.

19. Bh6 Ng4

I can see why this move would be attractive to Black, because it exchanges off more material, but it does create a possible target on g4.

20. Bxg4 hg 21. Bxg7 Kxg7 22. Qd4+ …

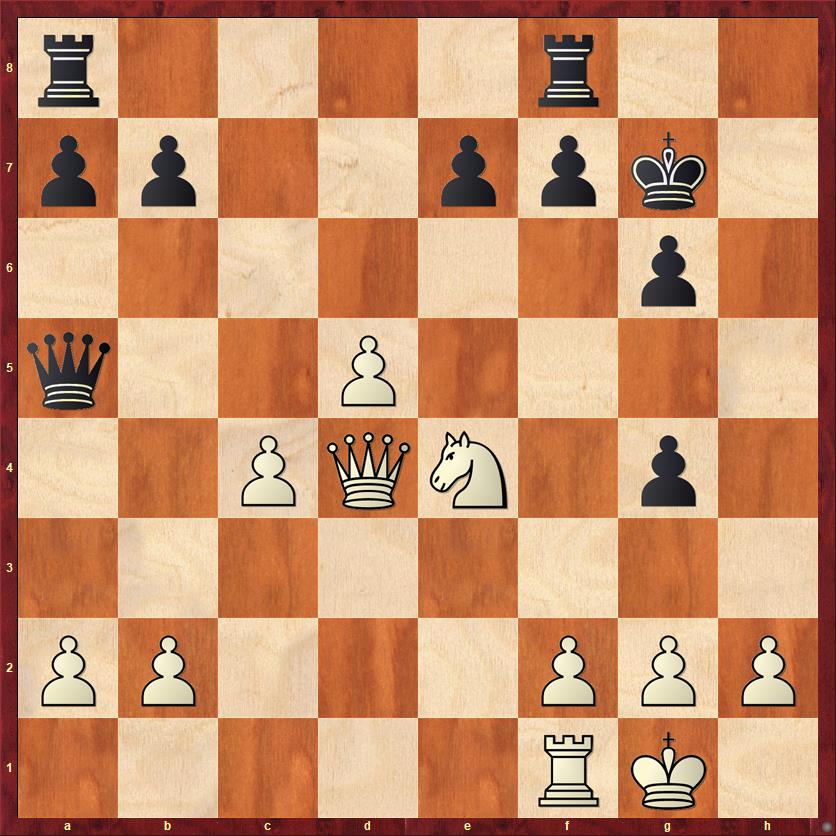

FEN: r4r2/pp2ppk1/6p1/q2P4/2PQN1p1/8/PP3PPP/5RK1 b – – 0 22

The most critical position of the game. How should Black get out of check?

I don’t envy Black’s decision, because both of the main options, 22. … f6 and 22. … Kg8, look uncomfortable. Obviously, 22. … f6 creates a huge weakness on e6, and the question is whether that weakness will be fatal. On the other hand, if Black plays 22. … Kg8 he has to deal with not one but two possible plans for White: 23. Ng5 with the idea of Qxg4, Qh4, and Qh7 mate; or 23. d6 with the idea of deflecting the e-pawn and playing Nf6+. Either way, it’s a scary position for Black.

22. … f6?

According to Fritz, 22. … Kg8! was the best choice. Both of the attacks I suggested fall short of winning. On 23. Ng5 the computer says 23. … Qb6! 24. Qxg4 Qxb2 25. Qh4 Qh8 and Black survives. On 23. d6 the computer says 23. … Rad8 24. c5 Qxa2 is good because it enables Black to transfer his queen to e6. Or 23. d6 Rad8 24. d7 Qf5 25. Rd1 Rxd7 26. Qxd7 Qxe4 with dead equality.

For these reasons the computer recommends for White to slow-play this position with 23. a3!, keeping the moves d6 and Ng5 in reserve, and its evaluation is about +0.4 to +0.5 pawns for White. Which is interesting, but I can tell you that there is absolutely zero chance I would have played that move. Even now, I find it very hard to pause in the middle of an attack to play a prophylactic move.

This game was, of course, played long before the computer was around to tell us perfect play. Kevin’s decision was reasonable, but now let’s see what goes wrong.

23. Nc5 Rh8 24. Ne6+ Kf7 25. Qxg4 Qxa2?

The only hope was 25. … Rag8, trying to bring maximum resources to the aid of the kingside. The computer then recommends 26. Qe4!, and the threat of d6 looms. Kevin’s move is too slow, and the final onslaught is upon him before he has chance to organize a defense.

26. Nf4 Rh6 27. Qe6+ Kf8 28. Re1 …

Throughout the game this has been the one White piece that struggled to participate in the attack. One of the problems for White in the variations after 22. … Kg8 is that there are very few lines where the rook does anything, because it has to hang back and defend the back rank. Now that it’s an active player, White’s attack quickly becomes overwhelming.

28. … Re8 29. d6! …

Finally. This move has been in the air for so long, and it’s appropriate that it’s the move that breaks down Black’s defense.

29. … Qxb2

Might as well grab all you can.

30. d7 Qb4

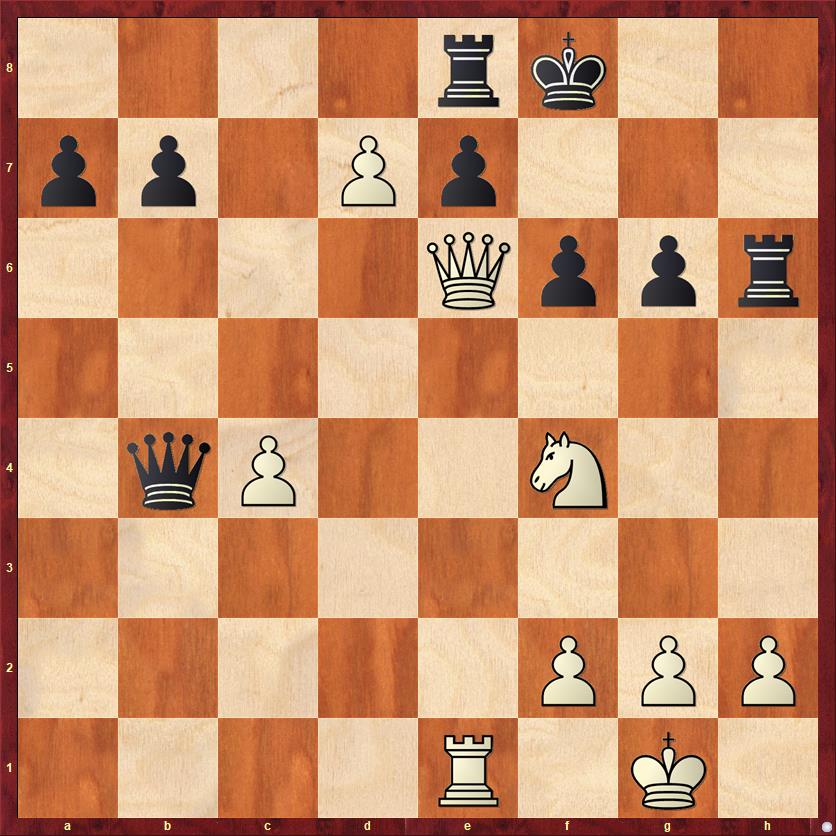

FEN: 4rk2/pp1Pp3/4Qppr/8/1qP2N2/8/5PPP/4R1K1 w – – 0 31

Now of course 31. deQ+ would win by brute force, but I found a way to put on a nice, decorative bow on this pretty game.

31. Qg8+! Black resigns

Mike Splane says that I’m not allowed to call this sort of move a queen sacrifice because I get the queen right back. Whatever. It’s mate in five after 31. … Kxg8 32. deQ+ Kg7 33. Rxe7+ Qxe7 34. Qxe7+ Kg8 35. Ne6 Rh7 36. Qe8 mate.

A really good game for understanding the balance between material and positional pressure.

Some lessons:

- I think that pawn sacrifices like 8. Qf3 (and, to a lesser extent, 12. d5) are particularly effective against players in the B-A-Expert range. These players are good enough that they seldom miss overt tactics, but they very often miss or misevaluate sacrifices for positional pressure.

- Sometimes a speculative sacrifice like 16. Rxd4 is a good way to reverse the momentum of a game. Prior to this move, the position was sort of trending in Black’s favor, with his knights becoming very active. After the sacrifice, Black’s pieces no longer coordinate as effectively.

- However, you should not count on speculative sacrifices all the time. If you can find a move that accomplishes the same goals and doesn’t sacrifice material, by all means play that one. One of my aphorisms is “Ruthlessness > Courage.” That is, a move that ruthlessly crushes your opponent is better than a daring and “brilliant” move that may backfire.

- When attacking, watch out for pieces like White’s king rook that aren’t contributing. Try to invite all your pieces to the party. An attack that doesn’t use all the pieces is often an attack that falls short (or draws instead of winning).

- When defending, try to avoid the creation of new weaknesses. Granted that Black had a difficult position after 22. … Kg8, it became impossible to defend after 22. … f6, which weakened both the squares e6 and g6.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

I think we must have just missed overlapping at Andover. I was there from Fall ’74 to Spring ’79. I love these historical articles, thanks for digging back into the old days.