After spending three posts on 1978, a huge year in my chess life and my personal life, let’s move on to 1979. It was my last year of college (spring) and first year of graduate school (fall), and a very strange year. Coming back from Russia to America, I felt detached from my old life and I felt much older somehow. I now had a girlfriend in Leningrad who was inaccessible to me, except via letters that took three weeks to arrive. It was far from clear what was going to happen next on that front.

Meanwhile, on the academic front I finished college in fine style, graduating with Highest Honors (one of four in my class). I was admitted to all four graduate schools I applied to, thus carrying on an odd tradition. When I applied to college in 1975, I was accepted to all four schools. When I applied to graduate school in 1979, I was accepted to all four schools. And when I had a huge life change in 1996 and applied to graduate school again, I was once again accepted to all four schools I tried. So my lifetime record in school applications is 12-0! I have now retired undefeated from school applications. I will never try to extend my record.

Out of the four schools (Princeton, Harvard, MIT, and Caltech, if you must know), I picked Princeton, where I spent the next four years studying for a Ph.D. in math. It was a really, really humbling experience. I had classmates who had already published research as undergraduates. I had classmates who had finished in the top ten on the Putnam Exam, the national collegiate math competition. (My best finish was 58th.) I had classmates who came to Princeton knowing exactly which world-famous mathematician they wanted to study with. (I didn’t even know who the world-famous ones were, or why they were famous.)

For a variety of reasons, but mostly because I was working so hard, I gave up on tournament chess for a couple years at Princeton. But 1979 was not one of them! The summer of 1979 was the last of the old-style summer vacations for me, when I came home and stayed with my parents and worked at my summer job at Byrd Press. I got to play plenty of tournament chess, 4 tournaments and 22 games.

I fully expected that when I came back from Russia, I would quickly rise to expert rank. After all, I had just held my own in a 14-round Russian tournament where half my opponents were candidate masters (stronger than American experts) and half were category I players (stronger than American class A players). But the expected improvement didn’t happen. The holes in my game were still too huge. I still had no positional judgement and too many games that were decided by mad tactical shootouts or by time scrambles.

But when it worked, it was entertaining as hell. Here is one of the craziest games of my tournament career, and most likely the only game I ever won with a queen and bishop versus two queens. It’s also a game where my opponent totally outplayed me before falling into the Twilight Zone.

Eddie Gerdy — Dana Mackenzie, 6/16/1979

1. e4 e6 2. d4 d5

As noted in my last post, this was the brief period in my life when I played the French Defense. As this game shows, I had no idea what I was doing.

3. Nc3 Bb4

The Winawer was de rigueur in those days, having been popularized by Viktor Korchnoi.

4. e5 c5 5. a3 Bxc3+ 6. bc Qc7 7. Nf3 Ne7 8. a4 Nbc6 9. Be2 Bd7?

At some point, either here or the move before, Black is supposed to play … b6 to fortify the c-pawn and guard against Ba3. But I didn’t know that.

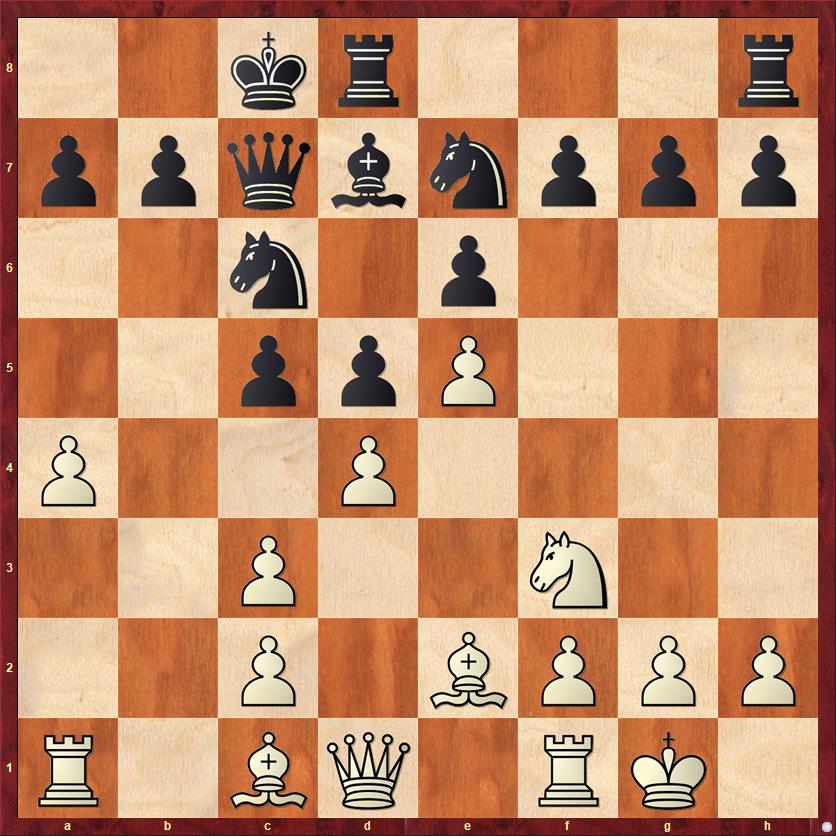

10. O-O O-O-O??

FEN: 2kr3r/ppqbnppp/2n1p3/2ppP3/P2P4/2P2N2/2P1BPPP/R1BQ1RK1 w – – 0 11

An absolutely horrible move that makes White’s Ba3 ten times more effective. You could tell my opponent knew it, too. For the next few moves he plays very powerfully.

11. Ba3 c4 12. a5! …

I like this move a lot. It threatens to trap Black’s queen. I’m just scrambling to survive.

12. … Be8 13. Qd2 f6 14. Bd6 Qd7

I think it’s likely that I would play 14. … Rxd6 today. With a slight material sacrifice, rook for bishop and pawn, Black would stop White’s initiative in its tracks. White has a couple of weak pawns, and the position is not a great one for White’s rooks because of the lack of open files. By contrast, 14. … Qd7 is the sort of move where you just close your eyes and hope you survive. Black’s congested, disorganized position is a mess.

15. Rfb1 Nf5 16. Bc5 Bh5

It’s very interesting to watch Black’s play in this game. My pieces gradually deploy on the kingside, where it seems as if I’m twenty tempi behind White’s queenside attack. White, for his part, plays like a stroke patient who has forgotten that the right-hand side of the board exists. From move 11 to 28, a span of 18 moves, every move he plays ends up on the left-hand side of the board. The funny thing is, the first 16 of them are actually perfectly good moves. It was just that sort of position.

17. a6! b6

No alternative. I saw the bishop sac coming, but everything else was worse.

18. Bxb6! ab 19. Rxb6 Bxf3

FEN: 2kr3r/3q2pp/PRn1pp2/3pPn2/2pP4/2P2b2/2PQBPPP/R5K1 w – – 0 20

Now White gets carried away just a little bit. He should just play 20. Bxf3, with a winning position. But that would require him to make a move on the kingside. He wants to win with only queenside moves.

20. Rb7? Qe8?

On 20. … Bxe2 21. Rxd7 Rxd7 22. Qxe2 Fritz evaluates the position as equal.

21. R1b1 Bxe2

Man, I keep taking all of his pieces on the kingside but he’s just not paying attention. And for good reason: he’s totally winning on the queenside.

22. Rb8+! Nxb8 23. a7 Qh5

The slow exodus of Black’s pieces to the kingside continues. The king is coming next. Can this possibly work?

24. axb8Q+ Kd7

At least I don’t have to think in this part of the game, I just have to run.

25. Rb7+! …

White isn’t holding anything back. And he doesn’t need to.

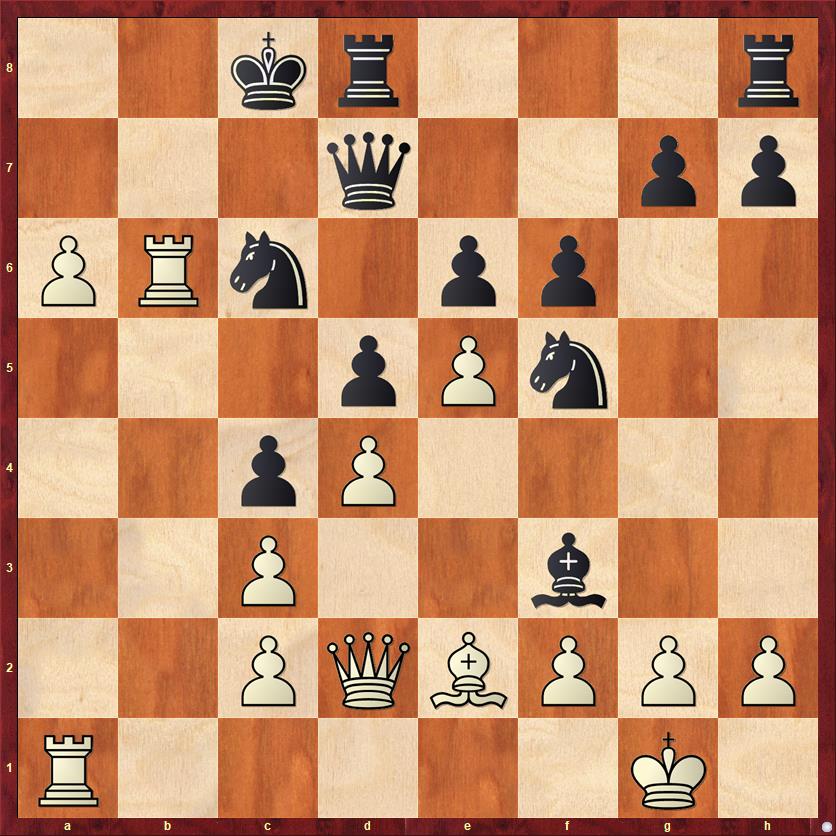

25. … Ke8 26. Qc7 Ra8!

On the list of sneaky moves I’ve played in my life, this one ranks pretty high. The computer now shows White with a mate in six. But no human alive would find it, because White has an easy way to win a rook that seems to leave him with a winning advantage.

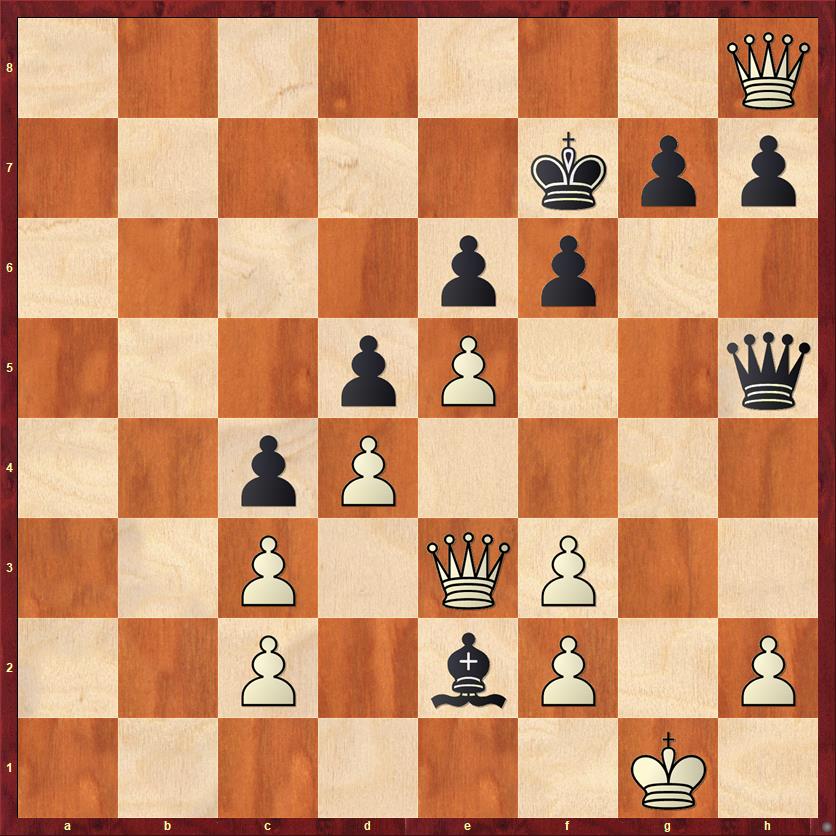

FEN: r3k2r/1RQ3pp/4pp2/3pPn1q/2pP4/2P5/2PQbPPP/6K1 w – – 0 27

I’ve already given you a huge hint: White to play and mate in six. Another hint is that Black can’t castle.

This is a truly problem-like position where you won’t find the answer by tactical thinking. Instead you have to think strategically. Most of Black’s pieces are rooted in place by mate threats. The knight can’t move. The queen can’t move, except to g6. The queen rook can’t leave the back rank. The king rook is irrelevant, and the bishop is irrelevant for defense. Because of this massive tie-down of Black’s pieces, White wins with the ridiculous quiet move 27. Qc1!!, threatening not only Qb2 but also the much more impressive 28. Qa3!!

If White had come up with this idea, I would very likely be presenting this as one of the best games ever played by an opponent of mine. But he tripped right at the finish line, playing what seems to be an obvious move — which actually costs him the victory.

27. Rb8+?? Rxb8 28. Qxb8+ Kf7 29. Qxh8 …

White’s first kingside move since move 11. It is a bad omen for him.

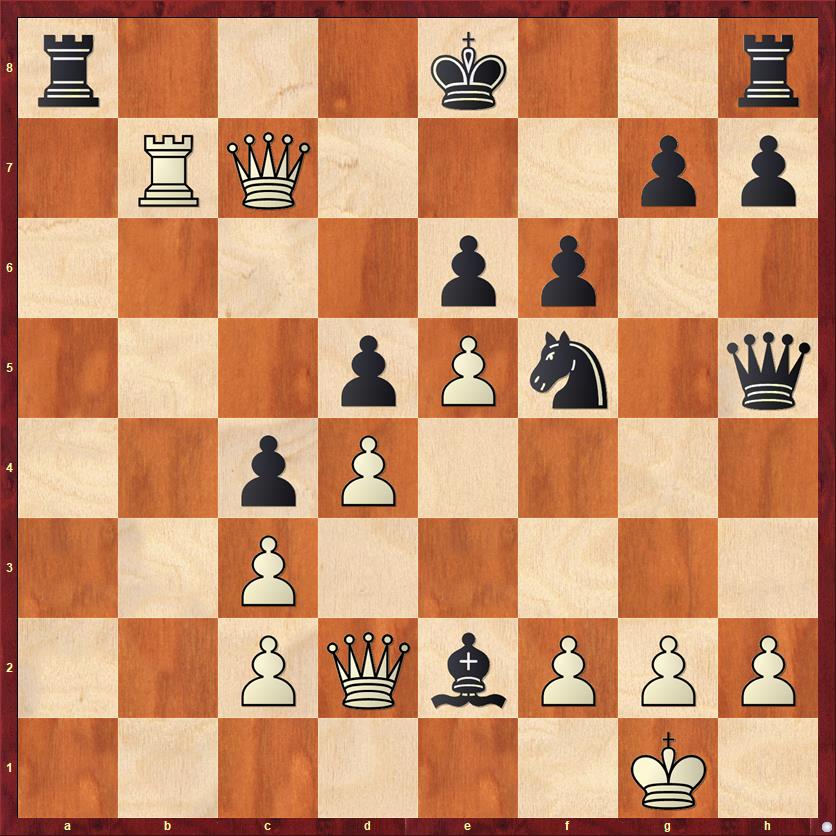

29. … Nh4

FEN: 7Q/5kpp/4pp2/3pP2q/2pP3n/2P5/2PQbPPP/6K1 w – – 0 30

All of a sudden Black’s counterattack, which has been proceeding at a glacial pace, is starting to look quite menacing. The threat is 30. … Nf3+, with checkmate to follow. How can White save the game?

Some tries that don’t work: (A) 30. Kh1? Qg4! (B) 30. ef? Nf3+! (C) 30. Qf4? Ng6! This one has to be my favorite variation. I have never seen any other position in a tournament game where a knight was able to fork two queens.

The only move for White to save the game is 30. f3!, which creates luft for his king. For a long time, from 1979 until tonight, when I put the game on a computer, I thought that this was winning for White. But it turns out that Black has an absolutely stupendous drawing combination that only a computer could find. Here it is: 30. … Nxf3+! 31. gf Qxf3 32. Qe1. So far so good. But how can Black make any progress?

Answer: 32. … Bd3!! My jaw absolutely hit the floor when I saw this on the computer, and it hasn’t come up off the floor yet. The idea is to transfer the bishop to e4, where the mate threat on g2 is apparently too strong: White’s queen will have to leave the back rank to defend it, and then there will be some kind of perpetual check or worse. So White takes the bishop, 33. cd, but allegedly in spite of being a queen up, White cannot escape the checks after 33. … Qg4+. Basically White has no control over the light squares, and that is why Black can check forever.

I know I run the risk of exaggeration, but this is one of the most astounding computer finds I have seen. As a practical matter, 30. f3! would probably have won for White, because there is no way I would ever have found this idea.

Instead the game ends in another beautiful way.

30. Qe3? Nf3+! 31. gf? …

The last chance was to give up the queen for two pieces with 31. Qxf3, when White might have drawing chances.

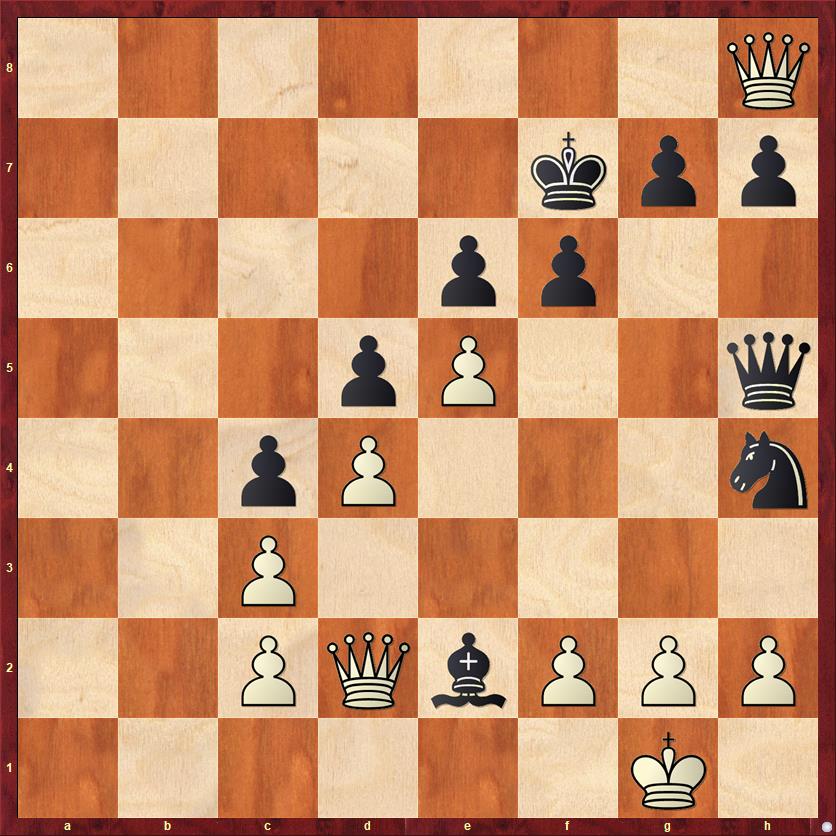

FEN: 7Q/5kpp/4pp2/3pP2q/2pP4/2P1QP2/2P1bP1P/6K1 b – – 0 31

There are some positions that make you ask, “How is this position even possible in a game between two good players attempting to make good moves?” This is one of them. How did White get two queens? How did Black’s bishop get to e2? Why hasn’t it been taken already?

Those questions are harder to answer than the other question, which is: How does Black win this position? The answer:

31. … Qg6+ 32. Kh1 Bf1!

The move my opponent must have missed. We have all seen checkmates on g2 a million times, but it always happened with the bishop on f3 or h3. Most of us have never seen it happen with the bishop on f1.

33. Qxg7+ Qxg7 34. White resigns

This game has to win some sort of prize, but I’m not sure what. Craziest Comeback Win? Best Game Ever By An Opponent Until He Made One Natural But Wrong Move? Most Ineffective Use of Two Queens? Slowest Mating Attack in History? Most Impertinent Knight? Most Ri-donk-ulous Computer Analysis?

How about “All of the Above”?

Lessons: There are no lessons from this game. I haven’t ever played any other games like it.

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

I belatedly noticed one other unusual thing about this game. I never captured any of White’s pawns! In the final diagram position he has seven pawns and two queens, one of the pawns having promoted to a queen.

Great comeback; a quintessential two-rook sacrifice template but with a different implementation.