My second translation for Crestbook has now been posted! This is a translation of a “KC-conference” with former FIDE World Champion Alexander Khalifman. The “KC” stands for “KasparovChess,” which is the name of the discussion forum at Crestbook. The KC-conferences are an ongoing series where members of the public can pose questions for the leading chess players in the world. The interview with Khalifman is the ninth one in the series, and it is going to be a two-parter (the second part will come in a few days).

I would like to encourage readers of my blog to (a) submit questions for future KC-Conferences (after I find out who the future interviewees will be), (b) submit questions for Khalifman if you have any, and (c) let other people know about this new opportunity for English-language readers to “get acquainted” with Russia and the former Soviet Union’s most famous players. Over the next few weeks I will gradually catch up with the translations of previous KC-conferences, and then we might be able to arrange a followup conference where the interviewees (people like Karjakin and Gelfand and Khalifman) would reply to the questions of English-speaking readers.

I’m sure that for many of my non-Russian readers, the name Alexander Khalifman will be vaguely familiar, but you might not remember exactly what he is known for. Allow me to refresh your memory! Back in the 1990s and early 2000s, when FIDE adopted the idea of holding a single knockout tournament to determine the title of “FIDE World Champion,” Khalifman was the very first winner. American chess players ought to remember this, because the tournament was held in our own country, in Las Vegas, making it one of the most important events ever held on American soil.

Nevertheless, many people consider the FIDE world championships to be sort of a second-rate title. See, for example, the interview with Karpov that I recently translated for Crestbook and excerpted in this blog. Or see Tim Harding’s recent column on www.chesscafe.com, “Thoughts on the World Championship,” where he writes:

In Kibitzer 40 (September 1999) I returned to the topic and asked “Is Khalifman the real World Champion?”, because we then had the absurd situation that the FIDE world title had just been won by a player who was forty-fifth on the rating list, 223 Elo points below Kasparov. The world champion has nearly always been in the top three or four rated players, if not the very top.

To me, some of the most interesting points of the Khalifman interview come when he addresses this issue of whether he was a legitimate world champion. I don’t want to spoil too much of the surprise for you, but I would say that behind his joking response there is some justifiably wounded pride.

Khalifman also has some interesting things to say about the current race for FIDE president, about the chances of Magnus Carlsen to become world champion, and about who he thinks are the true geniuses of contemporary chess. Excerpts are below. Remember that this is only a small part of the interview. For the full interview, surf on over to Crestbook! [Note: Names next to the questions are the user names of the people who asked them.]

Kit: What has changed in chess, so that nowadays after five or six rounds grandmasters talk about being tired, and after 10 or 12 rounds the participants really do look like very tired people in the press conferences? It seems as if they had no such problems in the past:

Goteborg, 1955 – 21 players, one round

Curacao, 1962 – 8 players, four rounds

Amsterdam, 1964 – 24 players, one round

And there were many others, as I’m sure you know better than me. Does it have to do with something other than chess? Are people weaker? The ecology worse? The stresses greater?

Khalifman: This is not complicated to explain, and human nature or ecology have nothing to do with it. In those golden days, the preparation for a game went something like this: “Should I play the King’s Indian today? Hmm… or the Old Indian? Oh well, what’s the difference anyway.†Now, without concrete preparation for the concrete opponent it is impossible to accomplish anything on the elite level, and so the working day has increased at least one and a half times. Correspondingly the pressures at the board on your thinking apparatus and your nervous system have also grown. In addition, the games used to be adjourned after 40 moves (in fact, this was still true when I got started), while now in the same game you might fall into time pressure two or even three times, and the stress grows in a geometric progression. In sum, to organize a tournament today with 20 or more rounds would be a mockery of chess and the players.

vasa: What move do you consider the most super-duper move of your entire career?

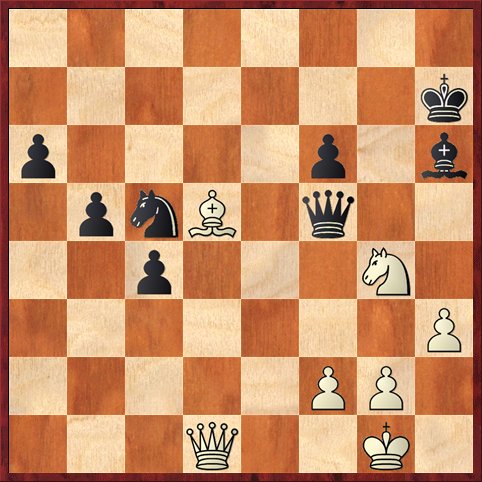

Khalifman: It’s not so easy to answer. For some reason the first thing that comes to mind is the missed opportunities, and there have been many of them. But in order not to deviate from the theme, I would say it’s the move 41. Qe1! in my game with Karpov (Reggio Emilia 1991/92).

41. Qe1! +–

As I was thinking about the position after the time control, I worked it all out to the end and became convinced that I was going to defeat one of the most outstanding chess players of all time. In general, I love exactly this unostentatious beauty of short moves. By the way, if you happen to see a score of that game in which this is the 39th move, don’t believe your eyes. Knowing my own habit of messing things up in time trouble, in the opening I did not forget to include the moves Ng5 Rf8 Nf3 Re8. And, as you see, it helped.

ot4eto: Greetings from sunny Bulgaria. How did you deal with the psychological burden of being champion of the world?

Khalifman: I won the championship at a fairly mature age, therefore life had already prepared me for being over-burdened. It was hard at first to accept the massive currents of hate that came my way, but I gradually got used to this.

gena: After this victory, did you consider yourself an equal classical champion in the line beginning with Steinitz-Lasker- … up to Kasparov, or did you somewhere in your heart of hearts understand that it wasn’t so?

Khalifman: Thank you for your undoubtedly good intentions, but it never even came into my head to consider myself the equal of Steinitz. He defeated Zukertort, but I had to master Kamsky, Gelfand, and Polgar. Now compare. (P.S.: Unfortunately, I often run into a complete absence of a sense of humor in my opponents. I hope that this does not apply to you, dear readers, but just in case I would like to add: Insert smileys according to your taste.)

In my perhaps uneducated opinion, a world chess champion should prove his superiority not only over one outstanding challenger, but over others who are, perhaps, equally outstanding.

I do not idealize the knockout system and I do not even have any thought of considering myself a great chess player, but nevertheless the ideal system for awarding the world championship has not yet been invented.

Neznakomets: How strong do you think Kasparov would be if he returned to chess today?

Khalifman: It’s always rather hard to answer “if only†questions, especially when you’re talking about something that is almost unbelievable. A very important question then would be: How and for what reason would this hypothetical return take place? After all, it’s one thing if he returns to play one tournament, and a completely different thing if he decides once again to battle for the highest of the heights, throw all his politics into the wastebasket, select a team of seconds, and so forth … The second scenario seems to me especially unrealistic, but in the former case he would probably play at about a 2750 rating.

Ruslan73: What are the personal characteristics that, in your opinion, are necessary to reach the highest level in chess?

Khalifman: Hmm, I don’t even know. It seems as if no matter what you say, you can find completely convincing counterexamples. One of the most valuable that comes to mind would be the presence of a specific talent for chess, but as my experience has shown, it is possible to become FIDE World Champion without even that. A strong will and a powerful intellect are also salutary, but some people manage to do pretty well without either one or the other. Sorry, but I won’t name any names.

Winpooh: Alexander, you wrote in your column on the match in “64†that Anand and Kramnik are geniuses, but Topalov is merely a talent. Could you develop this theme in more detail? And what place in the hierarchy of talent and genius can Magnus Carlsen aspire to, in your opinion?

This is, of course, only a subjective feeling. No special algorithm exists for measuring chess talent, and no units of measurement exist either. It simply seems to me that the talent of Anand and Kramnik is so outstanding that one can consider them geniuses. Topalov, of course, has great talent, but I can think immediately of ten other active chess players who are not less gifted. This number is already a little bit too large to consider all of them to be geniuses. This assessment is not intended in any way to offend Veselin. Quite the opposite. Talent comes from nature, but in order to achieve outstanding results with less talent, you need an extraordinary fighting spirit. The powerful natural gifts of Carlsen are obvious, of course, but for the time being I am not prepared to place him in the company of geniuses. Although this is, of course, more than likely.

phisey: Do you think that it was right for them to rename the FIDE World Championship as the World Cup? After all, the way that the players are competing is still not child’s play.

Khalifman: And why should one play at half strength for the World Cup?

To be serious, I have no formulated opinion on this question. Although the knockout system is far from ideal, the way that the world championship plays out today also does not seem to me to be the best solution, even with all of these sacred traditions attached to it. The most amusing part of this history is the fact that the tradition could have been completely different. In 1851, if I am not mistaken, a tournament was held in London by a system that is very close to the modern knockout tournaments. At the time, the most respected experts expected the winner to be the pride and glory of British chess, Howard Staunton, and then they expected to have a triumphal coronation. However, some unknown schoolteacher from the other side of the world interfered with their plans (Breslau? Where is that? What is that all about?) and the coronation somehow evaporated. If Adolf Anderssen had not made it to London in time, then today the traditionalist knockouters would be hurling insults at the reformer match-eviks. Tell me where it is written that in order to defend the champion’s title one should only have to defeat one opponent, even if it is a very strong one? History sometimes plays very interesting jokes on us.

Lolita: Alexander, I remember how you appeared on KC in the Afromeev case in the ranks of his exposers. [Translator’s note for Western readers: See Wikipedia article on Afromeev at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_Afromeev. To make a long story short, Afromeev, a businessman from Tula, made it onto the FIDE Top 100 rating list by means that are widely suspected to be fraudulent.] Now on the Chess Glum forum, you associate on very friendly terms with users nicknamed “Pots†and “Luganâ€â€”one of whom played in tournaments in Tula, and the other of whom was a defender of Afromeev. Have you changed your personal attitude toward Afromeev and his actions? Especially in connection with his initiative in supporting A. Karpov for president of FIDE? What is your opinion about fraud in chess and do you have any proposals for battling unethical players and organizers?

Khalifman: In recent times I have come to look at a lot of things more calmly. Of course, as before I have a negative opinion of Afromeev’s actions and as before I believe that the presence of such a personage in the leadership of the RCF is incorrect, to put it mildly. But I now have less desire to paint the world in black and white colors. Therefore, if someone takes a different attitude toward Afromeev and similar characters, that fact in itself is not enough reason for me to avoid having any relations with that person.

It is not my role to give advice to Anatoly Evegenievich [Karpov]. If he considers it acceptable to rely on allies like this—that’s his choice.

How, as a practical matter, to battle with phony titles and tournaments, I don’t really have a clear idea. Don’t forget that in this holy war it is very important not to discourage the desire of normal organizers to run tournaments.

Valchess: Alexander, it seems as if it would be appropriate to bring this round of the conference to a conclusion with a question about today’s “hot†topic—the competition between Karpov and Ilyumzhinov. Could you please formulate, more or less openly, your position? What is your opinion about the “election campaign�

Khalifman: I am waiting to see if a third candidate will declare himself. I cannot believe in Karpov in a directorial or leading role (especially in tandem with Kasparov), and the argument that “At least it can’t get any worse than it is†does not convince me at all. It can, and much worse! On the other side, the lack of desire (or inability?) of Ilyumzhinov to remove Makropoulos from his team, who has many times demonstrated a flagrant lack of respect for chess players, does not allow me even the slightest possibility to support that candidate. I do not know the nuances of the campaign, and I am not prepared to draw any conclusions from the things we see above the surface.

To be continued …

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

I would like to ask any of the currently active top players:

What is a typical day of study for you? I mean, do you do tactics puzzles, read endgame books, play out positions against the computer, if so what type of positions, etc.?