One of my favorite ChessLectures ever was called “Double Queen Sacrifices,” in which I talked about the ultra-rare games where one player sacrificed a queen twice in the same game. Many chess players don’t even sacrifice two queens in their whole lives, so two queens in one game is pretty amazing.

But this year there was a grandmaster game with something even more remarkable: one player offered two queen sacrifices simultaneously. I can imagine a composed problem with two simultaneous queen sacrifices, but I would never have believed it possible in a tournament game. Check out the finish of the amazing game between GM Artyom Timofeev (White) and GM Urii Eliseev from this year’s Moscow Open (February 2016).

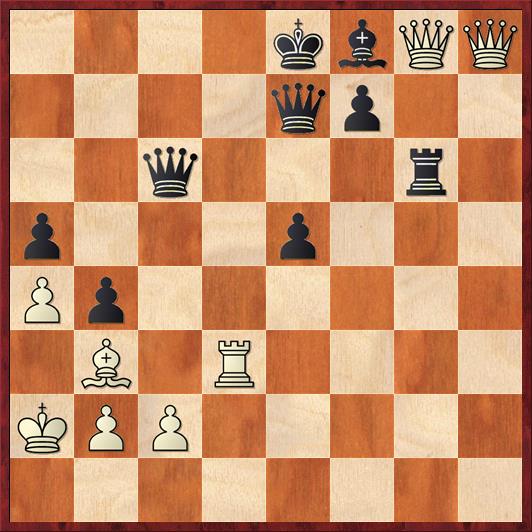

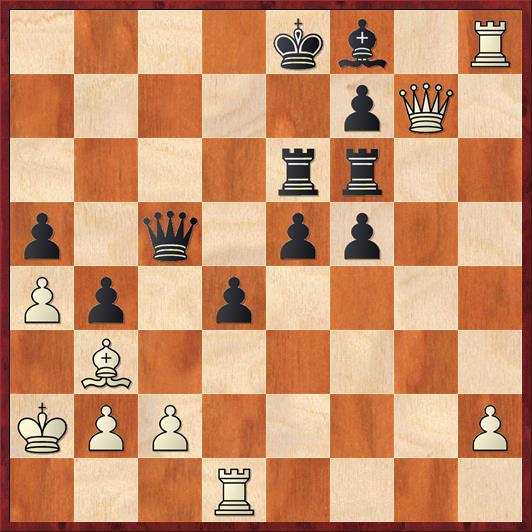

Position after 47. … Rg6. White to move.

Position after 47. … Rg6. White to move.

FEN: 4kbQQ/4qp2/2q3r1/p3p3/Pp6/1B1R4/KPP5/8 w – – 0 48

Yup, that’s right. Each player has two queens. Black has just attacked one of White’s queens with 47. … Rg6, doubtless expecting something “normal” like 48. Q8h7 Rh6, with a two-queen skewer. Do you see what he overlooked?

Answer: White played the unbelievable move 48. Qxe5!!, sacrificing both queens at once. If 48. … Qxe5 49. Qxf7 mate, or if 48. … Rxg8 49. Qb8+ quickly leads to mate. Black has nothing else even close to a defense; for instance if 48. … Qc7 to stop the mate at b8, 49. Qxf7 is still checkmate because of the pin on the e7 queen! So Eliseev resigned.

There have been famous four-queen games before, like the famous Fischer-Petrosian game from My 60 Memorable Games, but I doubt that any of them have ever had such a beautiful finish.

Even more impressive is the fact that the game as a whole was worthy of such a spectacular finish. It was an extraordinary battle with heroic attacks and defenses. As you’ll see, the four-queens situation happened “organically,” out of the natural flow of the game, not as any kind of attempt to make the position weird.

Let’s pick up the game on White’s 20th move. It was a Richter-Rauzer Variation of the Sicilian Defense. White has sacrificed two pawns but Black’s king is caught in the center.

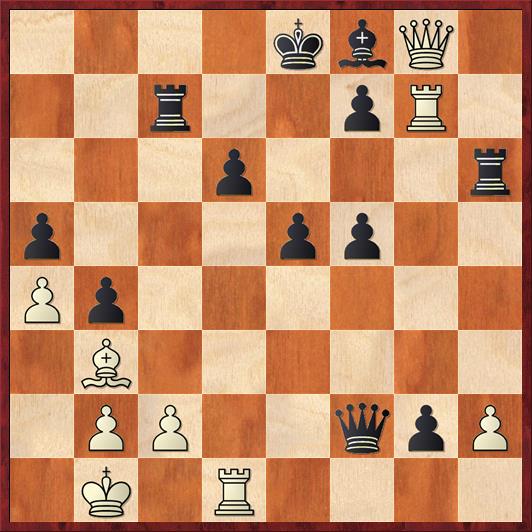

Position after 19. … Be6. White to move.

Position after 19. … Be6. White to move.

FEN: r3kb1r/5p2/pq1pbp2/4p3/1pB4p/4N3/PPP1Q1PP/1K1R3R w kq – 0 20

Here I’m torn between two questions: “How can Black possibly survive?” and “How can White possibly break through?” In fact, the remaining 27 moves of the game are a debate over those two questions. White has to play incredibly resourceful chess to break through Black’s massive cluster of pieces and pawns. On the other hand, it’s almost impossible to see how Black’s king can ever find safety.

This position is a great example of the richness of the extreme imbalances that modern grandmasters are willing to create in order to get winning chances. However, it’s very unlikely that Timofeev came up with the two-pawn sac on his own. He surely knew that Eliseev had reached exactly this same position two years earlier, in an action game against Alexander Grischuk. Grischuk had played 20. Qf3 and Eliseev came up with the very nice idea 20. … Ra7 21. Bxe6 fe 22. Qxf6 Rh6. Grischuk eventually won the game because he’s Grischuk, one of the top speed chess players in the world, but Eliseev had some reason to consider the opening a success.

Timofeev had likely gone over that game and thought that he had an improvement over Grischuk’s 20. Qf3: 20. Nd5! This very logical move makes Black’s pawn mass immobile and permanently cramps Black’s dark-squared bishop. It’s a good move for setting up a long-term bind. Eliseev could not allow the knight to remain, so he played 20. … Bxd5 21. Bxd5 Rc8 22. Qg4 Rc7 23. Rhf1 Rh6 (this idea again) 24. Rf3 h3!

Position after 24. … h3. White to move.

Position after 24. … h3. White to move.

FEN: 4kb2/2r2p2/pq1p1p1r/3Bp3/1p4Q1/5R1p/PPP3PP/1K1R4 w – – 0 25

A nice “monkey wrench” move by Black. He would like to disrupt White’s pawn structure and take over the g-file with 25. gh? Rg6. If White plays 25. Rxh3, which I think the great majority of chess players would do without thinking, the trade of rooks will take the steam out of White’s attack. For example, 25. … Qf2! 26. Be4 Rxh3 27. Qxh3 Qe2 and after 28. Qd3 or Qf3 Black will trade queens and have a better endgame. The nice thing about being two pawns up is that you can give one back and still be a pawn ahead!

The next move is when the game first starts to become mind-blowing, because White played

25. Rg3!

A move I never would have thought of! White doesn’t care about material. He cares about only two things: keeping all of the heavy pieces on the board and playing for checkmate. Watch how these themes play out over the next few moves. One point of this move, by the way, is to prevent 25. … Rg6 because of 26. Bxf7+!

25. … a5 26. a4 …

The sort of detail GM’s are so good at. Black doesn’t want to play … Qf2 right away because the b-pawn hangs, so he plays … a5. As for White, the move 26. a4 is incredibly important, giving his king a flight square. We’ll see in 20 moves or so that the safety of White’s king, compared to the dangerous position of Black’s king, is the decisive factor in the game. Now we resume the kingside battle.

26. … Qf2 27. Bb3 f5 28. Qg8 …

Where is the queen going? What is it doing? It’s all very unclear to me.

28. … hg

Why not, right?

29. Rg7!! …

Any normal player would play 29. Rxg2? but after 29. … Qh4! Black has a big advantage. He’s threatening 30. … Rh8 forcing a queen trade, and White’s “attack” is running out of steam. As before, Timofeev’s main goal is to get at the Black king, and he has to avoid rook or queen trades.

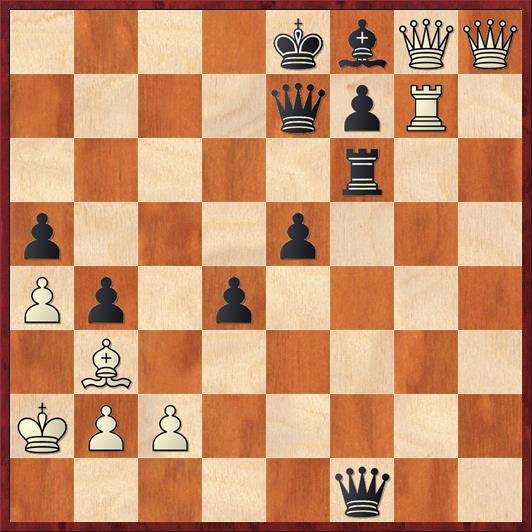

Position after 29. Rg7. Black to play.

Position after 29. Rg7. Black to play.

FEN: 4kbQ1/2r2pR1/3p3r/p3pp2/Pp6/1B6/1PP2qpP/1K1R4 b – – 0 29

If Black ignores the threat on f7 and plays 29. … Rxh2 then White would win with 30. Bxf7+ Ke7 31. Bg6+ Bxg7 32. Qf7+! Kd8 33. Qe8 mate! What a position! Black is ahead by a rook and three pawns, and is threatening to queen on the next move, but none of this matters because his king is in checkmate.

White’s 29th move must have come as a complete shock to Eliseev. Now Black has to scramble to avoid getting blown away, but he conjures up a brilliant defense.

29. … Rf6!

Eliseev’s rook play is remarkable in this game. When you play an opening line that involves not castling, you’d better find other ways to activate your rooks.

30. Rh7! …

Again Timofeev is not tempted to take the g-pawn. His sole mission is to checkmate Black. Nothing else will do.

30. … d5!

Amazing defense. This move prepares to bring the queen to c5, defending the f8 bishop. The pawn on d5 is attacked two different ways, but White can’t take it because of 31. Rxd5? g1Q+ or 31. Bxd5? Qxc2+.

31. Rh8 Qc5 32. Qxg2 …

This game is like a symphony, and every symphony has crescendos and quiet moments. Now, and again on move 34, White hits the pause button on the attack to take care of little details. Here he finally gets rid of the g-pawn that almost became a queen. This was Black’s one opportunity to trade queens with 32. … Rg6 33. Qxd5 Qxd5 34. Rxd5, but White probably has the advantage because he will win either the e-pawn or the a-pawn.

32. … d4 33. Qg7 Rcc6

It seems as if Black has built up an impregnable wall on the f-file. How can White ever break through?

34. Ka2 …

Unbelievably cold-blooded! In the midst of the attack, White pauses again, this time to remove his king to a safer location. I could never play this way.

34. … Rce6?!

Black continues to wrap his pieces in a protective cocoon around his king.

FEN: 4kb1R/5pQ1/4rr2/p1q1pp2/Pp1p4/1B6/KPP4P/3R4 w – – 0 35

35. Rg1?! …

This is the one place in the game where the computer questions both players’ judgment. Rybka says that White should go ahead and take the exchange with 35. Bxe6 Rxe6 and then 36. h4! leads to a better version of the pawn race in the game. But I can totally understand the humans’ reasoning. The bishop is such a great piece, both for offense and defense, that White is reluctant to part with it.

The move 35. Rg1 is too slow, and Black should now play 35. … e4 with at least equality. (In fact, it might turn into an immediate draw by repetition with 36. Rg5 Qc4+ 37. Kb1 Qf1+.) But what would be the fun in that?

35. … Rh6

Not a bad move — the computer says that Black is still equal — but Black keeps allowing some embers of White’s attack to keep going, and it eventually costs him.

36. Rg5 Rxh8 37. Qxh8 Rh6 38. Qg8 Rf6

For the second time a Black rook has settled here. But it’s kind of an awkward square.

39. Rg7 Qe7 40. h4! …

Position after 40. h4. Black to move.

Position after 40. h4. Black to move.

FEN: 4kbQ1/4qpR1/5r2/p3pp2/Pp1p3P/1B6/KPP5/8 b – – 0 40

At this point the game moves from being just another tough, hard-fought game to the realm of the surreal. Both players are in a sort of mutual zugzwang. Black’s pieces are totally paralyzed. And White’s pieces have “maxed out” — there is no way for him to increase the pressure on Black. So the only thing left for both players to do is race their pawns down the board!

Black actually does have one option instead of the pawn race. He could unpin his bishop with 40. … Kd7, and after 41. Rh7 the position is very unclear. (If 41. Rxf7+? Black happily trades rooks and he cannot lose the endgame. As I said before, one nice thing about being two pawns up is that you can give up a pawn and still be a pawn ahead.) However, it’s hard to fault Black for his next move. The pawn race appears to be in his favor because he queens first. If you’re going to get to a four-queens situation, usually the player who queens first will have the advantage. But not this time!

40. … f4 41. h5 f3 42. h6 f2

It’s too late for 42. … Kd7? 43. h7!

43. h7 f1Q 44. h8Q …

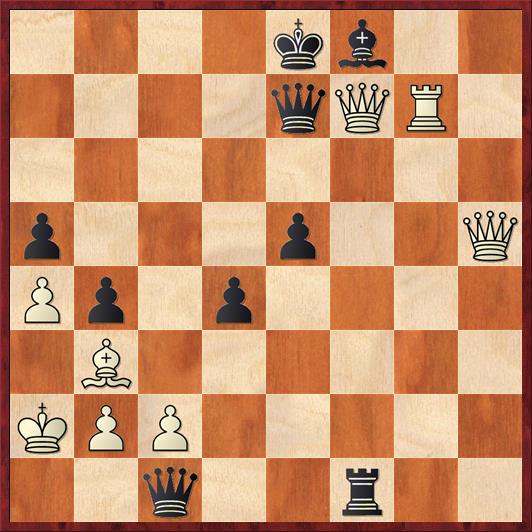

Position after 44. h8Q. Black to move.

Position after 44. h8Q. Black to move.

FEN: 4kbQQ/4qpR1/5r2/p3p3/Pp1p4/1B6/KPP5/5q2 b – – 0 44

This droll position is actually the first one I ever saw from this game, on a site called 1stmove, and I mistakenly thought that it was White to play and win. It was only after struggling and failing to find a killer move that I looked more carefully at the article and realized it was Black to move! That makes it even more remarkable that White eventually won.

Actually, it’s an interesting question: if it were White to move, could White win? This helps us clarify what the threats in the position are. According to Rybka, best for White (if it were his move) would be 44. Qgh7 Kd7 45. Qe4!, offering a rook sacrifice. (45. … Bxg7? 46. Qb7+ and White wins.) So one winning motif for White is to try to transfer a queen to the queenside via the long diagonal. If he can attack Black’s king from both directions, it will be hard for the king to survive the crossfire.

Now in reality it’s Black’s move. Eliseev again plays a move that the computer considers to be just fine, but in my opinion it sows the seeds of defeat.

44. … d3

Why this move? Well, the biggest contrast in this position is the absolute safety of White’s king compared to the crowd of White pieces hammering away at Black’s king position. Black wants to loosen up White’s king a little bit so that he can create some threats, too.

However, there was a cleverer way to achieve this goal, and I think it’s the move Black should have played, even though the computer considers it a blunder at first: 44. … Qc1! What I like about this move is that it gives Black real winning chances.

The first point is that 44. … Qc1! is to tie down White’s bishop. If White plays 45. Bc4?, which seems like a really good move (preparing to attack Black’s king from the other direction), Black strikes first with a pawn sacrifice and then a queen sacrifice: 45. … b3+! 46. Bxb3 Qa3+!! 47. ba Qxh3+ 48. Kb1 Rf1 mate. The nice thing about having two queens is that you can sacrifice one and still have a queen left to checkmate your opponent with!

Another very important point about 44. … Qc1! is that White can’t capture on f7. If 45. Bxf7+? Rxf7 46. Rxf7 Qxf7 is CHECK, so White does not have time for 47. Qxe5+ (which would otherwise be winning).

Yet another point of 44. … Qc1!, of course, is that Black threatens to play 45. … Rf1 and checkmate White on the back rank.

White could try 45. Qh3?, a variation on the idea of swinging a queen around to the queenside, but Black can block this idea with the simple 45. … Kd8. If 46. Bxf7 Rf1 or even just 46. … Qxc2, Black’s threats look stronger than White’s.

So for a while I thought that Black actually had a win here, but Rybka showed me that I was wrong. White’s correct response to 44. … Qc1! is 45. Qh5!! It looks as if Black is completely winning after 45. … Rf1 but no — White has a queen sacrifice (yes, another one!) 46. Qgxf7+!! that turns the tables.

Position after 46. Qgxf7 (analysis). Black to move.

Position after 46. Qgxf7 (analysis). Black to move.

FEN: 4kb2/4qQR1/8/p3p2Q/Pp1p4/1B6/KPP5/2q2r2 b – – 0 46

White’s queen sacrifice is an absolutely sick move, and I’m not even sure that Timofeev could have come up with it. The first point is that after 46. … Rxf7 47. Rxf7 Black’s queen on e7 has no way to escape discovered check. For instance, if 47. … Q7g5 48. Rxf8+!! Kxf8 49. Qf7 mate. The second point is that after 46. … Qxf7 47. Bxf7+ Kd8 48. Qh4+ Black has to allow White’s queen and bishop to penetrate. After 48. … Kc7 49. Bd5+ Bxg7 50. Qe7+ White’s queen and bishop are strong enough by themselves to force checkmate.

Even so, I still think that Black can draw. The drawing line is 46. … Rxf7 47. Rxf7 Kd8!, which just steps aside from the discovered check. White has nothing better than to take the queen, and after 48. Rxe7 Bxe7 49. Qxe5 Qg5! 50. Qxd4+ Kc7 I believe the game is drawn. Although White is a pawn up, there is no conceivable way to break the black-square blockade. As long as Black’s queen and bishop are near the king, White should not have any checkmates as in the last paragraph. And any queen trade will lead to a definitely drawn OCB endgame.

So to me, 44. … Qc1 is definitely the move Eliseev should have played. It is better than equal, and perhaps winning, in every variation unless Timofeev finds the miraculous idea of 45. Qh5! and 46. Qgxf7+! Even in that variation, it looks as if Black can hang on for a draw. Best of all, it’s very forcing. The move Eliseev played, 44. … d3, just lets White’s attack continue on and on. Under such pressure, Black is bound to slip sooner or later. Eliseev had to take his opportunity to “flip the script” and give White something to worry about for a change.

Moral: Chess is a battle for the initiative. I’ve said it over and over. Black never fully succeeded in taking the initiative away from White in this game. That’s why he lost.

Okay, now let’s get to the finish. After 44. … d3, White played 45. Rg1 and now Eliseev finally cracked: 45. … Qf3? I’m not sure why, because this is such an obvious pawn giveaway. The best move is 45. … Qf2, which also gives away a pawn after 46. cd, but gives the queen a beautiful centralized position after 46. … Qd4.

White continued 46. Rg3 Qc6 47. Rxd3.

Actually, I think I do understand why Eliseev went for this line. I think he actually wanted to reach this position, because he thought that after 47. … Rg6? he would win one of White’s queens. Little did he realize that Timofeev would offer both queens with 48. Qxe5!!, as we saw at the very beginning of this post. And Black resigned.

If you know of a more amazing game played this year, I’d like to see it! For Timofeev, this must have been the game of a lifetime. It isn’t just the double queen sac, it’s also the double pawn sac in the opening, and the relentless way he pursued the attack. For Eliseev, what a crushing defeat it must have been. In an incredibly difficult position he persevered and persevered — and (with the exception of move 34) the computer shows him as equal or better the whole way until he miscalculated with 45. … Qf3? So his opening variation remains unrefuted.

For chess fans, this game is such a wonderful treat. It’s sad that four-queens positions are so rare, because the tactical possibilities are just out of this world. As we saw, both sides had queen-sac possibilities. Perhaps we even learned two general principles about this ultra-rare type of position:

- In a four-queen position, it is a huge advantage to have king security.

- The good thing about having two queens is that you can sac one of them and still have a queen left to checkmate with.

P.S.: You might have expected Eliseev to give up on this opening. After all, he lost to Grischuk and he lost to Timofeev in epic fashion. But no, a month later he played it again against another strong GM, Darius Swiercz, in the Aeroflot Open. And this time he won! That, too, was an amazing game, and I might annotate it in my next post.

P.P.S.: There is no truth to the rumor that Black’s king and bishop were nailed to the squares e8 and f8 before the start of the game. It only seems that way.

P.P.P.S. (added six hours later): I only now realized that Urii Eliseev, who lost this game, was actually the winner of the tournament on tiebreaks! He finished with 7½-1½, and Timofeev finished at 7-2, tied for third.

The tournament web page had a very interesting interview with Eliseev, and of course they asked him about this game. This is what he said:

“After the defeat I did not feel any particular disappointment right away, because the game was extremely intense and it seemed to me that I truly played very decently. I’d say that I played the opening rather irresponsibly (that is, probably, the most precise word) and got into a very unpleasant position, which was particularly difficult to save when you look at it from the practical point of view. The computer, of course, shows some ways to keep an unclear battle going, but the position remained very unpleasant practically to the very end. Near the time control the play got very sharp, and I most likely underestimated the dangers that awaited me in the position with four queens; it seemed to me that I was creating some counterplay, and that the whole awkward setup of White’s pieces in the region of the squares h8-g8-g7 would not allow him to make concrete threats. But I was mistaken: the Black position was still critical. For that reason my defeat was justified, and therefore it did not have any particular demoralizing effect.”

{ 4 comments… read them below or add one }

Great game!

Actually, Timofeev already has a game to rival this one:

http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1566310

(#4 at ChessPro hit-parade for 2009)

Thanks! Timofeev-Khismatullin is pretty remarkable, but I think I like this one even better. The T-K game looked for a long time as if it was headed toward a draw, and things only started getting crazy at move 40. This one was tense and hard-fought throughout. I also think that the loser (Eliseev’s) play in this game was vastly more creative than Khismatullin’s play. Not that I’m criticizing Timofeev-Khismatullin! They’re both great games.

Another fun fact about this game is that despite the defeat, Eliseev managed to hold things together and finished 1st on tiebreaks in the event with 7.5/9. Timofeev got 7 out 9 and shared 3-9th

I think double queen sacks are not *quite* so rare but we tend to disregard ones of the form Qd8+ Rxd8 exd8=Q+ Rxd8 Rxd8# (which I got to play two tournaments ago) as they seem relatively trivial. (I was still pleased to get to do it, though.) I actually offered three queen sacks in that tournament, but the third was, alas, declined.

I have never seen a simultaneous double queen sack, though; that’s one you could go your whole life without seeing. I think a lot of us instinctively trade queens when there are four of them, because otherwise our heads might explode….

An interesting article could be written on positions with “too much” tension and how to resist the temptation to resolve them. For me personally, white pawns e4 d4 and black pawns e5 d5 (and all similar configurations) drive me crazy and I tend to capture right away just so that I won’t have to look at that THING anymore.