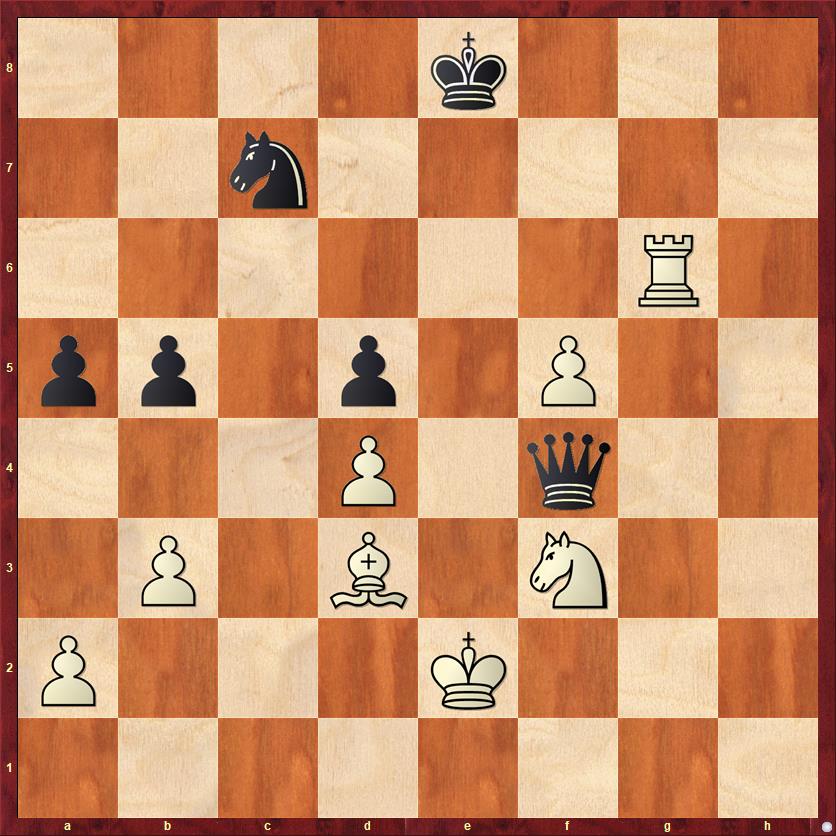

Here’s a position I reached in a recent rapid game against Shredder. I’m White, and it’s my move. The computer is set to a rating of 2321. One of the nice things about Shredder is that you can stop the clock even during a “rated game,” and I like to do this at most once per game as a training technique. (I’ve written a lot of blog posts about this before; Google “matrix chess.”)

FEN: 4k3/2n5/6R1/pp1p1P2/3P1q2/1P1B1N2/P3K3/8 w – – 0 45

What do you think about this position? Who stands better? What is White’s plan? Before I stopped the clock, I had four candidate moves: 45. f6, 45. Rc6, 45. Rb6, and 45. Ne5. Which of these would you choose?

If you’re Fritz 17, this is a trick question. One move is clearly worse for White, but every other move scores at 0.00. All three of the options I gave you, plus many more moves (45. a3, 45. a4, 45. b4, 45. Rg7) all get the “0.00” treatment. So if you’re a computer, you just pick one at random. For human players, however, I think that one of these moves really stands out. Not all “equal” moves are equal.

Let’s start with the Mike Splane Question: How am I going to win this game? The answer is, most likely by pushing the f-pawn, either queening it or forcing Black to make concessions (like the two queenside pawns) to stop it. So the move 45. f6 is a sensible one to look at, but it lets Black activate his knight too easily: 45. f6? Ne6, when the d-pawn falls and White’s position crumbles.

45. Ne5 is a very interesting idea. Of course, the d-pawn is poisoned because of 45. … Qxd4?? 46. Rg8+ Ke7 47. Nc6+. However, I was not able to find a convincing way to escape Black’s checks after 45. … Qh2+. Running to the queenside is a good way to lose: 46. Ke3 Qh3+ 47. Kd2 Qh2+ 48. Kc3?? b4 mate! For a while I thought that White could stop the checks by bringing his king to f2 and then interposing his rook on g2. Thus, for example, 45. Ne5 Qh2+ 46. Kf3 Qh3+ 47. Kf2 Qh2+ 48. Rg2 Qf4+ 49. Ke2, and Black is out of checks. But if we compare this to our original position, has White really made progress? I don’t think so. He’s improved one piece (the knight) but “de-improved” another (the rook) and, most importantly, White has not gotten any closer to the proposed winning plan of f6. I decided to play this variation only if I could not find anything better.

If you like Nimzovich-style prophylactic chess, then 45. Rc6 is the move for you. Black’s knight has no moves and his queen has almost no moves. Unfortunately, the king does have moves, and after 45. … Kd7 the rook is just going to have to move again. Alternatively, I could play 46. Ne5+, but again I had the feeling this move was premature. White’s king has even less shelter from the checks than it did before.

So 45. Rb6! was my last best hope, and it’s a pretty darn good hope. Here are all the great things about this move:

- It puts the rook on the “good” side of the f-pawn, where it prevents … Ne6.

- Therefore it threatens 46. f6, which will be White’s response on most “do-nothing” moves by Black.

- It also threatens the b-pawn. This is not meaningless; if I can win both the a- and b-pawn, even if it costs me the f-pawn, I will have chances to win the game.

- It also gives my rook access to the back rank, which is very important because it takes me just two moves (f6 and Ne5) to get mate threats. Those threats are particularly important in line (A) below.

- It’s also worth remembering something I said in another recent post: When you can tie down your opponent’s stronger piece with your weaker piece, then you should try to attack on the part of the board his stronger piece can’t get to. Here, White’s knight and bishop are doing a nice job of immobilizing Black’s queen. So White should try to get the most he can out of his force advantage (R versus N) on the queenside.

So what could possibly go wrong after 45. Rb6? Well, one thing we have to look at is the possibility of active defense for Black by

(A) 45. … Qc1. Although I could play 46. Bxb5+ here, I think that the more incisive way to go is to let Black’s queen eat all the pawns it wants while I set up a checkmate: 46. f6! Qb2+ 47. Kf1! Qa1+ (… Qc1+ also runs out of checks) 48. Kg2 Qxa2+ 49. Kg3. After 49. … Qxb3 or any other Black moves, the mate threats after 50. Ne5 are too strong.

(B) Another really cool and really thematic variation occurs after 45. … Kf7. On the surface, a very logical move because it intends to meet 46. f6 with … Ne6. Now, however, the time is right for White’s knight to leap into the fray with 46. Ne5+! Suddenly Black’s queen is going to be the target of a blizzard of forking threats. The king has to go to the g-file, because either 46. … Kf8 or 46. … Ke7 would be met by 47. Ng6+, and 46. … Ke8 47. Rb8+ once again forces Black’s king into a fork. (Again we see the usefulness of being able to check on the back rank!) After either 46. … Kg7 or 46. … Kg8 White plays 47. Rg6+. I’ll leave you to work out why both moves to the h-file lose for Black. The only other possibility is 47. … Kf8, which is met by 48. Rf6+! This move was somehow hard for me to see, stepping in front of my own pawn, but the tactics all work. If Black’s king goes to g8 or e8, then White will play 49. Rf8+!!, sacrificing the rook to set up Ng6+. So 48. … Kg7 is the only move to avoid all the forks. But now White plays 49. Rf7+ Kh6 50. Rxc7! This cold-blooded win of a piece also wins the game. Black no longer has a perpetual check because my king will run to either b2 or b1 and then I will interpose the rook on c2 or c1! What a fantastic, unbelievable line!

(C) After finding forced wins in variations (A) and (B), which seemed like Black’s two most thematic responses, I was really pumped. However, I then came to the move that is really best for Black: 45. Rb6 Kf8! This modest move vacates the e8 square for the knight, which is now prepared to come into the game via e8, f6, and then either e4 or g4 (the latter being especially dangerous for White). The best answer I could find was 46. f6 Ne8! 47. f7! The f-pawn is dead anyhow, so I might as well create some trouble with it. Now 47. … Kxf7? loses to 48. Ne5+. I thought also that 47. … Nf6 48. Ne5 looked very strong for White, because it looks as if White escapes the checks after 48. … Qh2+ 49. Kf3 Qh3+ 50. Kf4, marching right up the board. Unfortunately, my analysis was flawed: Fritz comes up with 50. … Nd7, which supposedly saves the draw (although against a human I would probably play on). Finally, on 47. … Qxf7 48. Rxb5 Black’s queen cannot defend both the a-pawn and the d-pawn, and I thought that this endgame too would give me some winning chances. (Fritz again disagrees and says it’s a draw.)

Bottom line: 45. Rb6! has a clear winning plan (two of them, even), and it leads to a forced win if Black plays either of his two most obvious moves, and even on the computer-like defense 45. … Kf8, White may still have winning chances. It’s by far White’s best chance to win.

Now let’s see what happened!

45. Rb6! Kf8!

Of course, the computer plays the computer-like defense.

46. f6 b4??

My jaw dropped. Of course a human would play this move, because humans would worry about losing the b-pawn and a-pawn. But after my lengthy timeout analysis I knew that 46. … Ne8 was Black’s only hope. Since my opponent is a computer, I can only conclude that either Shredder evaluated the endgame in variation (C) differently from Fritz, or it didn’t play the best move because it was “dumbed down” (but only slightly) to 2321.

Either way, I make no apologies. My play gave Black the most chances to go wrong. A human probably would have gone wrong, and even the computer went wrong. Black is now a tempo too slow to defend.

47. Bg6 Ne8 48. f7 Nf6 49. Ne5 Qh2+ 50. Kf3 Qh1+

Or 50. … Qh3+ 51. Kf4, which is exactly like the line in (C) above except White is a tempo ahead and wins after 51. … Nd7 52. Nxd7+ Qxd7 53. Rb8+.

51. Kf4 Qh4+ 52. Kf5 Kg7 53. f8Q+! …

The triumph of White’s strategy.

53. … Kxf8 54. Rxf6+ …

At this point both computer programs say that White is easily winning. However, I was sweating bullets for the rest of the game. Endgames with rook, knight, and bishop versus queen are not exactly an everyday occurrence, and I was scared to death that I would blow it. Fortunately, the winning plan is not very subtle: surround and ingest the d5-pawn with my minions, and then push the d-pawn to victory. I’ll give the rest of the moves with no comments.

54. … Kg8 55. Bf7+ Kh7 56. Ng4 Kg7 57. Be8 Qh3 58. Rg6+ Kf8 59. Ke6! …

Okay, one little comment: Never forget about the power of checkmate threats, even in the endgame. They often allow you to get away with “impossible” moves, as in this position where White is able to leave his bishop on e8 unprotected.

59. … Qh7 60. Nh6 Qe7+ 61. Kxd5 Qe2 62. Rg8+ Ke7 63. Nf5+ Kf6 64. Rf8+ Kg5 65. Ng3 Qxa2 66. Ne4+ Kh6 67. Ba4 Qc2 68. Ke5 Qc7+ 69. Kd5 Qe7 70. Re8 Qc7 71. Nc5 Qf7+ 72. Re6+ Kg5 73. Kc6 Qa7 74. Re8 Kg4 75. d5 Qf7 76. Re4+ Kf5 77. d6 Qg6 78. Re6 Qg2+ 79. Kc7 Qd5 80. Kb6 Kf4 81. d7 Kg4 82. Rc6 Kf5 83. Rc8 Black resigns

After 83. … Qd6+ 84. Bc6 Black has no more checks and no way to stop the promotion of the d-pawn. I like the way that all of White’s pieces are working together.

Lessons:

- The Mike Splane Question is a great way to orient yourself in any position. Fortunately, computers do not know about this question. Many humans don’t know about it either.

- When you can immobilize a strong piece with weaker pieces, you should be able to use your force advantage on a part of the board the strong piece can’t get to.

- Checkmate is a surprisingly strong weapon in the endgame — usually not as an end in itself, but as a threat that enables you to make “impossible moves.” See move 45, variation (A), and move 59.

- Timing is everything in the endgame, and there are billions of positions where a tempo is worth more than a pawn. See Black’s move 46, which saved a pawn but lost the game.