For the last month, since I got back from my disastrous tournament in Minneapolis, I haven’t shown any games from it because I thought they would be too embarrassing. But in order to learn from a failure, you have to face it and ask what happened and why. So now I’m going to start analyzing my games. Heck, maybe I’ll even show you all of them!

The first one I’ll show you is really, really embarrassing. I played like a class-C player in this game, no better. I failed in every phase of the game. I failed the opening, which I didn’t know and didn’t have a plan for. I failed at positional play, creating weaknesses that led to more weaknesses. And finally, I failed at tactics, missing a little combination that turned my opponent’s advantage into a rout.

But from your point of view — the reader — it’s actually good that I played so badly, because it gives you a chance to see how a master clinically dissects inferior play.

Kevin Wasiluk — Dana Mackenzie

1. d4 Nf6 2. Nf3 d5 3. c4 e6

I have experimented a little bit with 3. … Bf5, but I was trying to play sounder openings in this tournament. But I quickly ran off the rails anyway!

4. g3 …

As I said in an earlier post, I have never studied the Catalan Variation enough to know what I am doing as Black. In the early years of my chess career, no one ever played it. That began to change in the 1980s. By now, I would venture to say that it’s the main line in double d-pawn openings (or at least it’s fighting with the London Variation for the title of “main line”).

One of my readers, Roman Parparov, said that I should consider playing the Dutch Defense to avoid all of these Catalans and Londons. Ironically, in this game I did end up in a Dutch Stonewall-type formation. But I was improvising, and it didn’t end well.

4. … Bb4+ 5. Bd2 Bxd2+

After the game my opponent said that he considers 5. … Be7 to be the most annoying variation. The point is that Black has lured White’s bishop to d2, where it kind of gets in the way of the other pieces. An example variation is 5. … Be7 6. Bg2 O-O 7. O-O dc, where White could reply 8. Ne5 if his bishop were still on c1. But with the bishop on d2, 8. Ne5 is unplayable and White has to look for other ways to recover his pawn, such as 8. Qc2.

This is a good example of the kind of insight you get when you study an opening. But I haven’t studied the Catalan. My move isn’t bad, of course, but it doesn’t really have a plan behind it.

6. Qxd2 Ne4 7. Qc2 O-O 8. Bg2 Nc6?

This is too slow, especially in conjunction with my next move. If I’m going to play … f5, which is already a slow and time-wasting move, then I should not compound my problems by wasting tempi with my queen knight. If I’m going to play … f5, I need to play … Nd7 and … c6.

Basically, my play here shows a lot of confusion. Yes, there are many Catalan variations where Black does play … Nc6, trying to put pressure on White’s weakly defended d-pawn. But the combination of … Nc6 and … f5 does not work very well.

Why didn’t I know this? Well, I just don’t play a setup like this very often. I’ve spent most of my chess career trying to get to positions with active piece play and open lines, rather than variations like the Stonewall with static pawn structures.

9. O-O f5 10. Nc3 g5

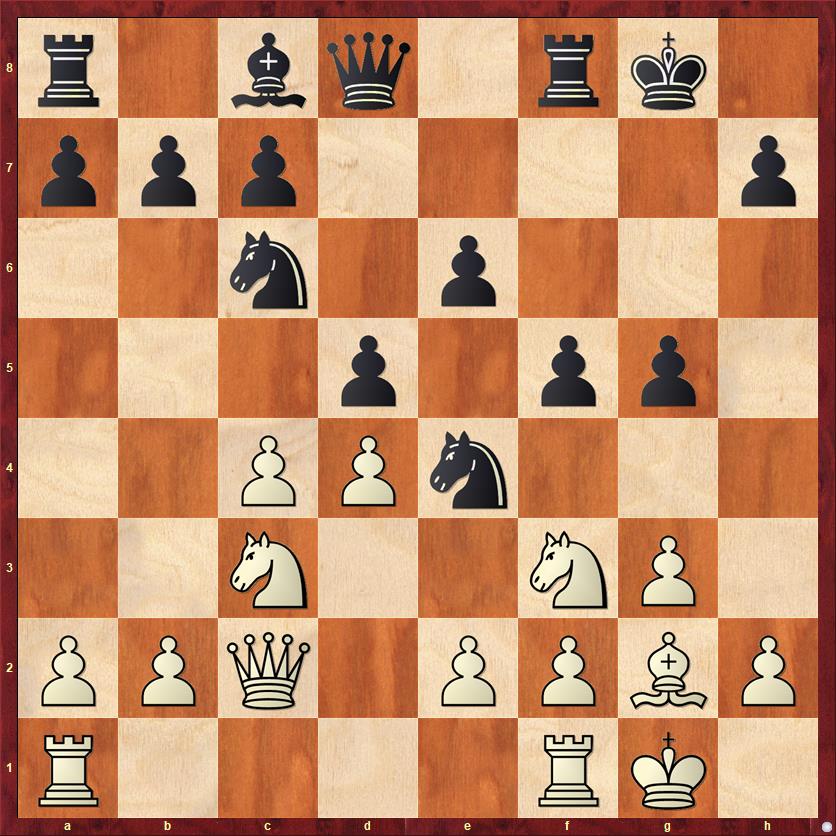

FEN: r1bq1rk1/ppp4p/2n1p3/3p1pp1/2PPn3/2N2NP1/PPQ1PPBP/R4RK1 w – – 0 11

A good case study of something I call “propagating weaknesses.” Because my d5 pawn is so shaky, I really want to defend it with … Ne7 and … c6. But if I play 10. … Ne7 right away, I didn’t like the way that his knight can just set up shop on e5, and then he can evict my knight from e4 with f2-f3 at some point. So I decided that first I would chase his knight away from f3 with … g5-g4, and then I would play Ne7, etc.

You might want to ask yourself, what’s wrong with this plan? Propagating weaknesses are the clue. By trying to rid myself of one weakness, I saddle myself with another.

11. e3 g4

I was actually pretty happy here. Because of the moves e3 and … g4, it becomes impossible for him to evict my knight with f2-f3. So what could possibly go wrong?

12. Ne`1 Ne7 13. Nd3 c6 14. cd cd 15. Rfc1 …

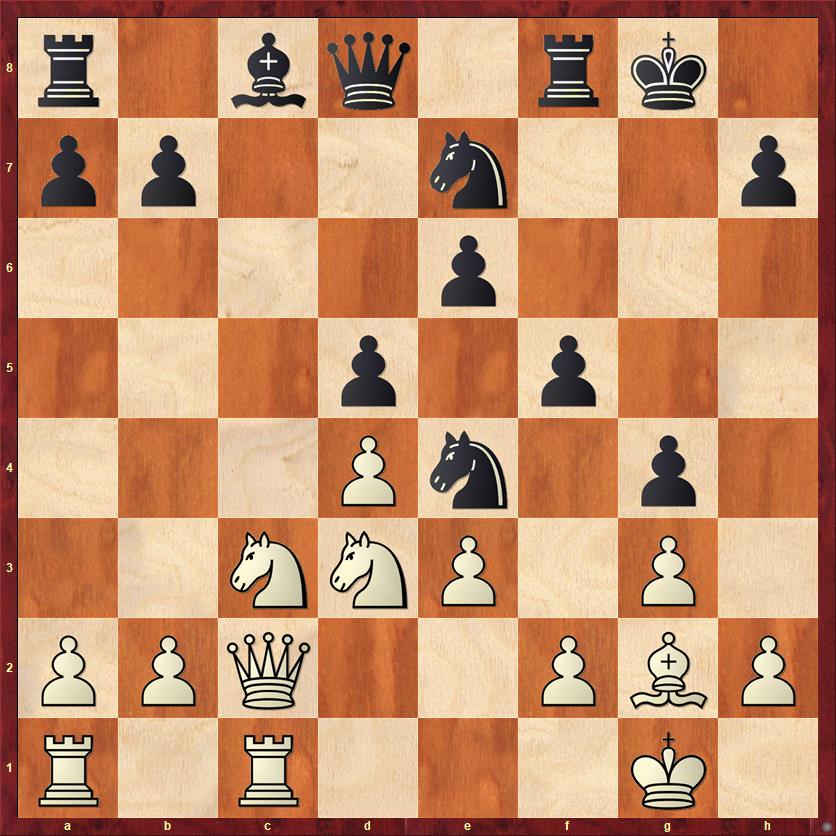

FEN: r1bq1rk1/pp2n2p/4p3/3p1p2/3Pn1p1/2NNP1P1/PPQ2PBP/R1R3K1 b – – 0 15

When we went over the game afterwards, my opponent (a FIDE Master) surprised me by saying that he thought he had a strategically won game at this point! My assessment during the game was very different. I knew that I was a little bit behind in development, but as compensation, I thought I had a strong knight on e4 that could not be dislodged.

Knowing what happened in the game, I think that his evaluation was much closer to the truth. Because of the “propagating weaknesses,” his knights now have two beautiful outpost squares, e5 and f4. And in fact, the threat of a knight coming to f4 is even stronger than the threat of a knight on e5, because the knight on f4 will target the most sensitive square in my position: e6.

15. … Bd7 16. Qb3 Bc6?

I hated playing this move. You can tell from my scoresheet, because I took 18 minutes on it, my longest think of the game. Actually, I hated all my options: 16. … Rb8, 16. … b6, 16. … Nd6, which are all purely defensive moves. What I really wanted to do was sac my b7 pawn, but I couldn’t find any variation that would give me plausible compensation for a pawn. The move I finally played was not good because it weakens e6 even more. Probably the least-worst option was 16. … Nd6, but of course this was hard to play psychologically because I thought the knight on e4 was the one good thing about my position. Emotion won out over objectivity.

17. Ne2 Ng6 18. Nef4 Nxf4 19. Nxf4 Qe8?

Again, not realizing how bad my position was. My last chance to stay in the game was 19. … Ng5. I need to keep at least one “good” minor piece on the board.

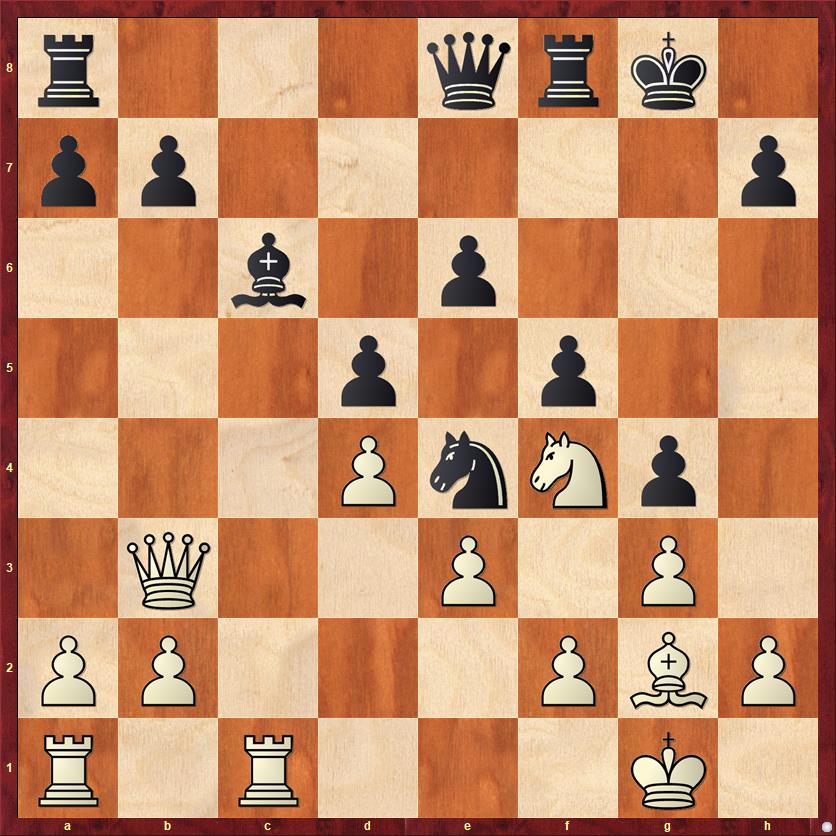

FEN: r3qrk1/pp5p/2b1p3/3p1p2/3PnNp1/1Q2P1P1/PP3PBP/R1R3K1 w – – 0 20

Now comes White’s nicest move of the game.

20. Bxe4! …

What a shock this was! I had been operating under the assumption that White would never want to trade his bishop for my knight, which would open up the f-file and create huge light-square weaknesses on his kingside. But I wasn’t looking at the concrete position. White’s move is completely justified, both strategically and tactically. Tactically, it simply wins a pawn. I couldn’t believe I had just given away a pawn so easily! Strategically, Wasiluk correctly assessed that (a) he has the dominant minor piece, and my bishop will never be able to take advantage of the weak light squares on the kingside; (b) he has the superior development, and the invasion of his rooks on the c-file will trump my dreams of attack on the kingside; (c) Black’s king is every bit as vulnerable as White’s king.

20. … fe 21. Qd1 …

A simple, quiet move that leaves Black defenseless.

21. … h5

Alternatively, if Black gives the pawn back immediately, say with 21. … Rf5, then White might play something like this: 22. Qxg4+ Kh8 23. b4! (to pry open the c-file) 23. … h5 24. Qh4 Qf7 25. a4 Rg8 26. b5 Be8 27. Rc8 Rg4 28. Qd8! and White’s attack is stronger than Black’s. However, this kind of computer analysis is, to me, less convincing than the three points labeled (a), (b), and (c) in my note to move 20.

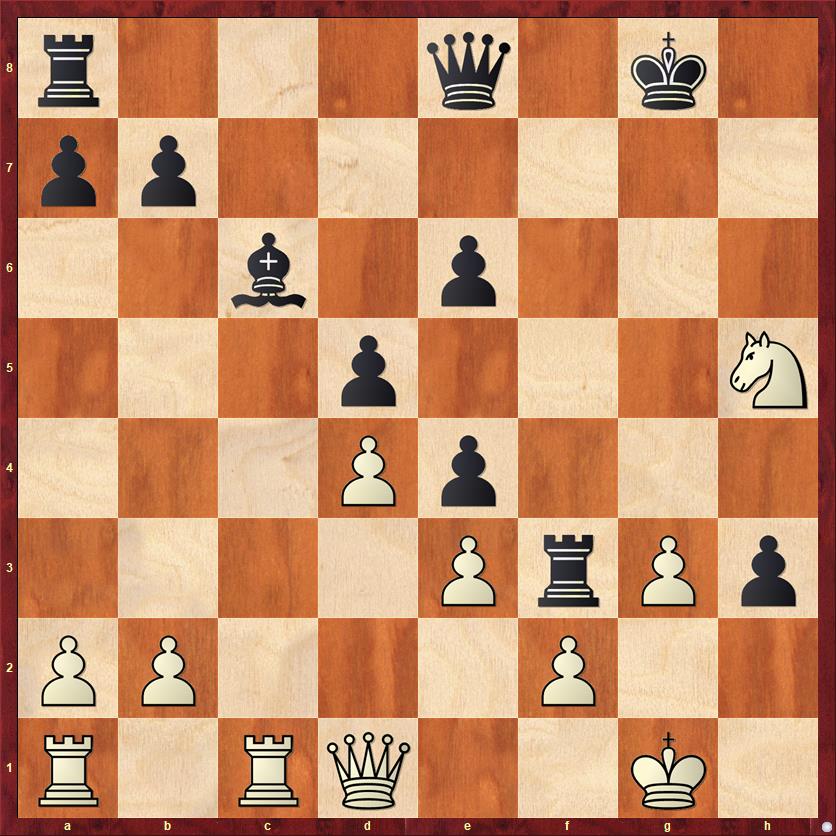

22. h3 gh 23. Nh5 Rf3??

FEN: r3q1k1/pp6/2b1p3/3p3N/3Pp3/4PrPp/PP3P2/R1RQ2K1 w – – 0 24

My last move sums up my whole tournament in a nutshell. Having gotten in trouble through ignorance of the opening and positional mistakes (propagating weaknesses), I seal the deal with a catastrophic tactical oversight.

I was dreaming of trying to create some mischief on the kingside after 24. Nf4, when White awakened me from my dreams with

24. Qxf3! …

Oh, good grief. The rest of the game needs no comment.

24. … ef 25. Nf6+ Kf7 26. Nxe8 Rxe8 27. Kh2 e5 28. de Rxe5 29. Rd1 Kg6 30. Rd4 Kg5 31. Rg1 Re7 32. g4 Re4 33. Rg3 Rxd4 34. ed Bb5 35. Rxf3 Kxg4 36. Rxh3 Kf4 37. Re3 Bd7 38. Re5 Bc6 39. Kg2 a6 40. f3 b5 41. b4 Bb7 42. Kf2 Bc6 43. Re6 Bb7 44. Re7 Black resigns

Looking at this game, I feel as if I was in denial of reality all the way from move 10 to move 24, and it was only after 24. Qxf3 that I realized that I had been living in dreamland the whole time.

While I have concentrated in my notes on the mistakes I made as Black (because I want to do better next time), I do want to point out how smooth and convincing White’s play was. Every piece was just where he needed it to be at just the right time.

Lessons:

- Improvisation is a poor opening strategy against masters.

- Don’t let your emotions get in the way of an objective assessment of the position.

- Weaknesses beget other weaknesses.

- If you have a “bad” minor piece, try to keep at least one other minor piece on the board so that you won’t end up in a hopeless good piece versus bad piece endgame.

- Stay alert for tactics, always. Even if your position is already bad, don’t make it worse by allowing your opponent a tactical shot. Or if your position is already very good, stay alert for tricks that your opponent might miss because of discouragement. (Interestingly, this part of the game cannot be practiced by playing against computers, because computers never get discouraged and almost never miss elementary tactics.)

And finally, on the lighter side, here is what my foster kittens thought of my bad bishop on c6. Bad bishop! Bad, bad bishop!

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

https://www.chessgames.com/perl/chessgame?gid=1012185

Also, John Watson quotes Kramnik saying that the g2 bishop is barely better than the c8 bishop in the Stonewall.

You’re a much stronger player, but as someone who has played (and lost) a whole lot of Stonewalls, I want to underscore that the QN is generally misplaced on c6 where it both weakens your center by preventing …c6 and cannot back up the strong e4 knight. Knights are the stars of the Stonewall and need to get to good squares.

Painful game of a familiar kind. Minor piece trades are very tricky in these lines; because of the inflexibility of the pawn structure a bad piece tends to remain bad. (Though there is a mysterious chess law that says if the QB *does* get out, it will be terrific. Got to sack a queen once on the strength of that bishop, which had slowly squirmed its way to f3.)

Hello Dana.

Everything said until and at move 15 is right. But before 14. …cxd5 is a mistake.

No experienced Stonewall-player would play this move!

After this you are ending up in a Slav exchange-like position, in which you had also (or already) played …f5 and …g5 (and following …g4). As results your white-squared bishop is bad, you have overextended on the kingside and attacked there too early. And White is dominating on the c-file and can for example try entering on c7 with options like Nb5.

This type of position is nearly lost for Black.

The ideas of recapturing …exd5 is to get rid of a potentially weak pawn and maybe also having the option of playing on the e-file with the queen following a setup with …Qe8/Qe7. You have to accept a pawn structure as in a Karlsbad-type postion of QGD and defending against a minority attack. But in Stonewall-positions you can attack with …Qe8 peeking out for …Qh5 and …Rf6 and maybe following Rh6.

In Europe there had been 2 good and influential middlegame books about 1955 – 1960.

One was the three volume series “Moderne Schachstrategie / Modern Chess Strategy” by Ludek Pachman from CSSR. There had been a second edition of it in the end of the Seventies after his imprisonment in Prague and his emigration to Germany, but there is nothing really new in it.

The second was the booklet series “Het Middenspel/ Das Mittelspiel/ The Middlegame” by Euwe and Kramer consisting of 12 small booklets, also available as a complete book. [A second edition or say overworking has been tried by the strong chessplayer and journalist G. Treppner, but stopped after he suddenly deceased.]

In this book the Stonewall-formation is deeply analysed and explained – which on the other hand is nearly completly lacking in Pachman’s books (which are neverless good and instructive).