Today I found out that my lifetime total of International Masters defeated had increased by one… and I didn’t even have to lift a finger!

The catch is — as everyone knows — that the best time to defeat a chess genius is when they are still young and have not come into their full powers yet. And in the San Francisco Bay area, there are many, many opportunities to play against (and occasionally defeat) young geniuses. In a Facebook post yesterday, Michael Aigner listed fifteen (!) players who started playing in this area and earned their International Master titles since 2000. Here is the Michael Aigner Honor Roll, listed in rating order:

- Sam Shankland (Grandmaster, current USCF rating 2784)

- Daniel Naroditsky (GM, 2702)

- Andrew Hong (IM, 2610, top age 16 in the U.S.)

- Steven Zierk (GM, 2584)

- Christopher Yoo (IM, 2582, top age 14)

- Vinay Bhat (GM, 2570)

- Balaji Daggupati (IM-elect, 2496)

- Cameron Wheeler (IM, 2488)

- Josiah Stearman (IM, 2482)

- Gabriel Bick (IM, 2475)

- Yian Liou (IM, 2469)

- Kesav Viswanadha (IM, 2457)

- Dmitry Zilberstein (IM, 2447)

- Ladia Jirasek (IM, 2433)

- Vignesh Panchanatham (IM, 2427)

Michael omitted two names from his list who I think should be there, in part because they would soar almost to the top of the Honor Roll:

- Samuel Sevian (GM, 2747)

- Hans Niemann (GM, 2724)

Both of these players started out in the Bay Area but earned their titles after they left: Samuel Sevian moved in 2012, became an IM in 2013 and a GM in 2014, while Niemann moved in 2015, became an IM in 2018 and a GM this year. Arguably we in the Bay Area can’t take “full credit” for their success. But I personally think that Sevian was probably already IM strength when he moved away and certainly would have earned his IM title if he had stayed. Niemann is perhaps not as clear but I think that he certainly owes a big part of his success to the many strong players he faced and opportunities he had in the Bay Area.

Of course, with all of these players the biggest factor was their own ability and desire. I can’t emphasize that strongly enough. But given those things, the Bay Area chess scene gave them the opportunity to flourish.

Michael’s post elicited some discussion over how the Bay Area would stack up if it were a country. Almost everyone agreed that Iceland was the most impressive chess country on a per capita basis, with 10 GM’s and 10 IM’s in a population of 360,000. But how many of those have earned their titles since 2000? How many countries with fewer than 8 million inhabitants (the size of the Bay Area) can boast of 17 players who have earned IM or GM titles since 2000?

The other fun thing to do when you see Michael’s Honor Roll is to ask what your record is against these people. As it turns out, I have not made the most of my chances to win a game against a future GM or IM. I’ve gotten a lot of draws, but only three wins. Here’s the breakdown: against Sevian, one draw; against Naroditsky, one draw; against Zierk, one draw and one loss; against Bhat, two wins (!!) and one loss; against Daggupati, one win; against Wheeler, one loss; against Stearman, one loss; against Bick, one draw and one loss; against Liou, one draw; against Viswanadha, one loss; against Jirasek, one draw; and against Panchanatham, one draw. Overall, +3 -6 =7 for a 40 percent winning percentage. (But against the future grandmasters, +2 -2 =3 for a nice 50 percent winning percentage!)

The reason for Michael’s post was that he wanted to congratulate Balaji Daggupati for completing all the requirements for the IM title. He has not received the title yet, but all that is left is FIDE’s rubber stamp.

Now I have to confess that when I first read this, I shrugged my shoulders, because I don’t actually remember Balaji. Not even one little thing about him. But then I looked back over my past game records this morning, and was surprised to find that I had actually played him once! It was the New Year’s Open in Santa Clara, in 2015, when he was rated 1961. And though I don’t remember the person, I do remember the key position. I’m playing Black, so I will show it from my side.

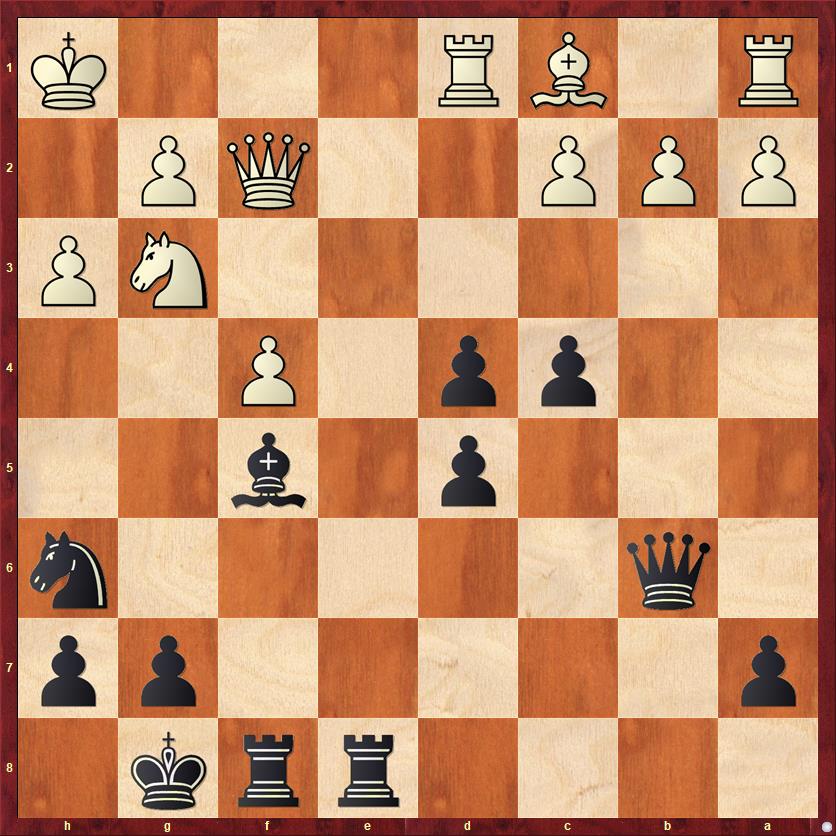

Balaji Daggupati — Dana Mackenzie (after move 25)

FEN: 4rrk1/p5pp/1q5n/3p1b2/2pp1P2/6NP/PPP2QP1/R1BR3K w – – 0 26

In this position, which came from a Two Knights Defense, White has been building pressure against Black’s lightly protected d-pawn. The question is whether he can get away with taking it, with 26. Qxd4. It does look a little bit scary for White. Black can try the Hook-and-Ladder Trick with 26. … Re1+, but there is no bite to it because White can just move his king aside with 27. Kh2. Or Black can play for control of the back rank in a more conventional way with 26. … Bxc2 27. Qxb6 ab 28. Rxd5 Re1+ 29. Kh2. But what comes next? If Black had some way of parachuting his other rook to the back rank to take advantage of White’s undeveloped queenside, then I would be winning. But there is no apparent way to do that. The computer evaluates the position as dead even (Black has compensation for the pawn, but no more) after 29. … Nf5. To be honest, in my notes after the game I wrote, “25. … Bf5 was nothing more than a good bluff.”

But it was a bluff that worked! Daggupati was convinced that he needed to finish developing with 26. b3?, but this move gives me the tempo I needed — not exactly to save the pawn, but to play a pawn sacrifice that really did have some bite. I continued 26. … d3 27. Qxb6 ab 28. Nxf5 Nxf5 29. cd c3!

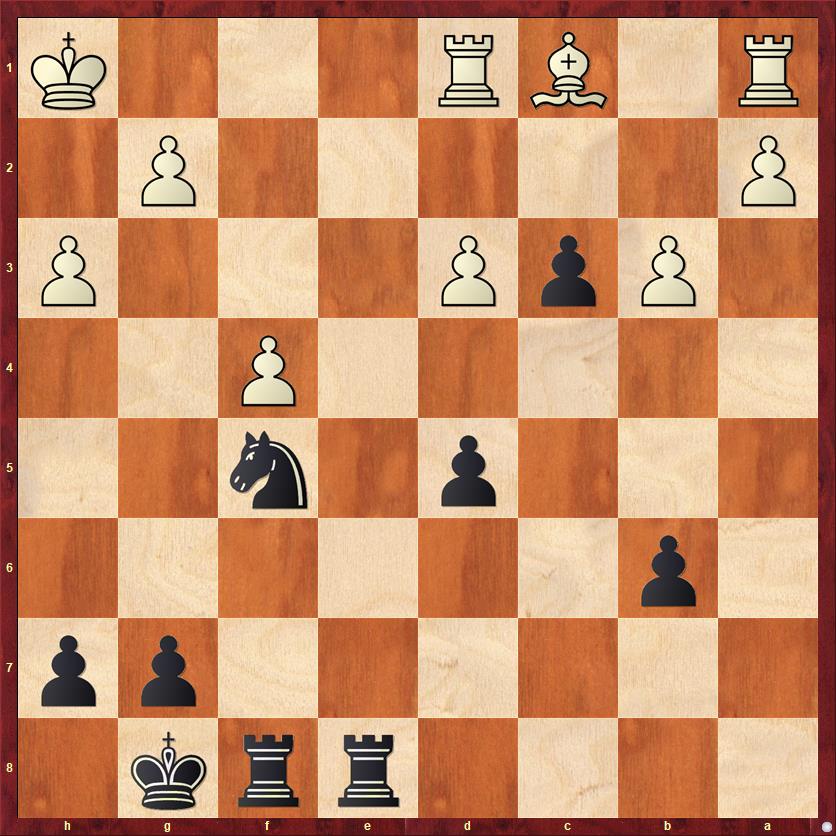

FEN: 4rrk1/6pp/1p6/3p1n2/5P2/1PpP3P/P5P1/R1BR3K w – – 0 30

This was surely the move that Daggupati missed. It’s amazing to see how my knight and pawn vacuum up almost all the squares that White’s bishop could move to. The only square left is a3, but that’s a really awkward place because it leaves him vulnerable to skewers on the a-file. Besides playing a good defensive role, my c-pawn is also a serious threat to promote, because my knight has no difficulty finding squares to assist it on its journey to c2 and c1.

The game continued as follows: 30. Ba3 Rf7 31. d4 …

Trying to deprive the c-pawn of protection. Another interesting way to play would be 31. Re1, with the idea of taking over the e-file. The computer comes up with this nice variation, where White gets his rook behind the c-pawn but then all of Black’s pieces work together to chase him away: 31. Re1 Rxe1+ 32. Rxe1 Ra7 33. Bb4 c2 34. a4 (trying to keep my rook out) Nd4! (Now the knight eyes the square b3, followed by queening the pawn) 35. Re8+ Kf7 36. Rc8 (seemingly stopping the threat, but now Black’s king just ambles over and there is nothing White can do about it) 36. … Ke6 37. Ba3 Kd7 38. Rc3 Rc7, and the rooks come off and the pawn promotes. A very pretty “slow-motion” variation.

After the move in the game, 31. d4, I played 31. … Re2 32. Rac1 Ra7. If he wants to, White can win the c-pawn with 32. Bb4 R7xa2 33. Rxc3 Rxg2, but Black has doubled rooks on the seventh rank and White’s king is in a mating net. After a long thought, Daggupati decided to give up the bishop with 33. Rxc3 Rxa3 34. Rc8+ Kf7 35. Rc7+, and Black won.

Actually I’m sweeping something under the rug by saying “and Black won.” Here I should probably have played 35. … Ne7, retaining a huge advantage because of my hyperactive rooks. Instead I played a little bit too conservatively with 35. … Re7?, which basically gives away my positional advantage in order to trade into an endgame with a winning material advantage of knight versus two pawns. I was confident I could win that endgame and I did, but it dragged on for 35 more moves (!) before Daggupati finally resigned on move 71.

One of these days, I hope, I will meet Balaji Daggupati at a tournament and congratulate him in person on his IM title!