There is No Santa Claus; Is There an Enterprise?

Saturday, January 30th, 2010

For months we’ve been waiting to hear what the Obama administration response would be to the Augustine Commission report on the future of NASA’s manned space flight program. Now it looks as if we have our answer, and it ain’t pretty.

The Augustine Commission outlined four possible directions for NASA. The last two were called “Flexible Path” and “Moon First.” The first two could be called “Moon Never” (though the report used different names). The commission further argued that in order to have a human space program that our country could be proud of, NASA’s budget would have to be augmented by about $3 billion per year.

As reported here and here and many other places, it looks as if President Obama has now placed his bets on the more ambitious of the two versions of “Moon Never.” Here is what I wrote about this option in my post from September:

Moon Never, ISS on Life Support. Slightly more palatable, this option also abandons hope for sending humans beyond low Earth orbit, but it at least acknowledges that it would be a disgrace to build a space station for 25 years, operate it for 5 years, and then torpedo it. The Augustine committee said that we can keep the ISS going to 2020 by developing a smaller heavy-launch rocket and relying on commercial companies to generate cheaper alternatives for launching humans into orbit.

This pretty much describes what I have read about the proposal Obama is going to send to Congress, although we can now paint in a few more details. There is some talk that the space budget will increase by $1 billion per year (not $3 billion per year). In early January, the word was that this money was going to go to NASA but now looks as if it might go in part toward incentives for private companies to build launch solutions. Obama is definitely scuttling the Constellation program and its associated rocket, the Ares I-X. This is a bridge-burning move. Even if we changed our minds and wanted to send astronauts to the moon by 2020, or even the mid-2020s, without Constellation we wouldn’t have the hardware to get them there.

Of course I am disappointed by this decision. However, it was not the least bit surprising. In today’s economy, with talk of a budget freeze on discretionary spending, where was Obama going to find $3 billion? I consider some of the online criticism of his decision to be disingenuous; I suspect that many of his critics would have jumped on him, perhaps even harder, if he had chosen to ask Congress for another $3 billion per year for NASA.

I’m disappointed that Obama didn’t take more seriously the commission’s finding that NASA needed this money to have any kind of credible manned flight program. It wasn’t really a choice between $18 billion and $21 billion. It was a choice between $18 billion flushed down the toilet, or $21 billion producing tangible results.

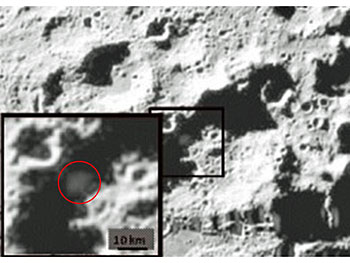

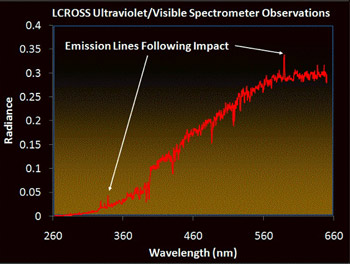

I’m disappointed also that there was no acknowledgement of the fact that, after the discoveries this fall concerning lunar water, the moon is actually an interesting destination again. Even if we concede that short-term financial considerations prevent us from having a viable human spaceflight program for a few years, a leader who was truly committed to space would outline a long-term strategy and a rationale that would include sustainable presence in space as its #1 objective. The best arguments I have seen in that direction are the ones on Paul Spudis’s blog. When you make that the rationale, the moon becomes a required destination, not an optional one.

However, I do see some reason for optimism in Obama’s decision, bleak as it may seem. It really does mark a break with the past. Gone is the pretense that NASA can do everything. Until now, there was always the hope that there was a Santa Claus, that the U.S. government or taxpayers would somehow step in and make NASA’s wishes come true. It’s possible that this was in some way holding back the efforts of private companies and investors to think creatively about what they could accomplish in space.

Now, there is no other game in town. We will only get as far in space as international partners and private companies, such as SpaceX, can take us. Lovers of free enterprise should be delighted; this is a chance to show that entrepreneurs can be better at “the vision thing” than presidents. For the near future, it seems, we are hitching our wagon to a starship named Enterprise.

I personally have some doubts. I’m not sure that space exploration companies are ready to walk on their own two feet. But we are going to find out, one way or the other.

A metaphor for the future of human spaceflight?

(Image from www.startrek.com.)