New Scientist article

Tuesday, April 6th, 2010

My article for New Scientist about the discovery of more-abundant-than-expected lunar water finally reached the newsstands last week. I’d like to welcome any readers of that article who have come to this blog looking for more information.

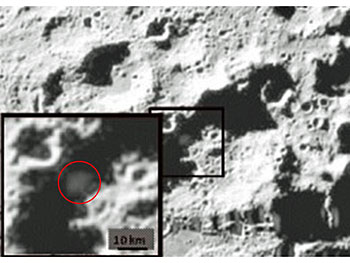

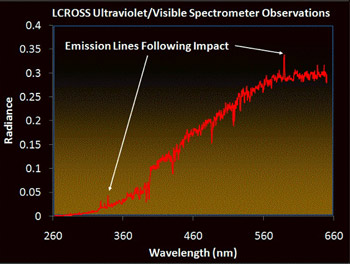

This article had quite a long gestation period. I first pitched the idea of an article about the LCROSS mission to my editor about a year and a half ago, but at the time she didn’t really see the news value of the story. Before the LCROSS mission lifted off, there wasn’t a whole lot of excitement about it in the media. But then a lot of things changed. The Chandrayaan-1 discovery of surface water on the moon. David Letterman’s skit that poked fun at the idea of “bombing the moon.” The very successful impact that dug up a lot of water, plus other volatile compounds.

At the same time, a big policy debate was going on about our future in space, with the Augustine Commission issuing its report about the same time as LCROSS was hitting its target. That debate culminated in February, when President Obama recommended the cancellation of the Constellation Program and redirected NASA’s priorities for the next decade.

With all of these things going on, I think it is fair to say that the moon and lunar water was one of the top stories in solar system science over the last few months.

I wrote the first draft of the New Scientist article in December, following the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group meeting in Houston (November) and the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco (December). I really wanted the article to come out then, when it could still (maybe, in some far-fetched scenario) have had some effect on the policy debate.

However, the article got delayed until April, not for any political reasons but just because New Scientist feature articles get put into a queue and it takes some time for them to work their way through that queue. Meanwhile, the Obama decision happened and so I had to revise the article to reflect that reality.

In the end, I failed in my original goal of writing an article that would perhaps have an influence on the future. However, I do think that the article itself came out a little bit stronger as a result of the delay. I was able to replace some of the “ifs” and “possibly”s and “could be”s with more definite statements. In some sense it became a retrospective on the lunar water story of 2009, rather than a story-in-progress as I originally conceived it. However, I would like to emphasize that there is still a story in progress, as the LCROSS data and LRO data continue to come in and become better understood.